Opening Scenes

“Whirl up, sea—

Whirl your pointed pines.

Splash your great pines

On our rocks.

Hurl your green over us—

Cover us with your pools of fir.”

H.D, Oread (1916)

Film Opening Technique #1: Close-up shot, followed by zoom out

We start with a line. An indentation.

You can depict air in motion with a set of three horizontal lines drawn in parallel, one above the other. You can suggest a gust or a change in direction by the flick or curve of a line’s tail. The point is: a line is enough, and a whole weather system can hide inside of it.

Pay attention to the proximity of one line to another. The width between them can indicate pressure or intensity or a knot. Be aware that you cannot physically see wind, so you must determine the strength of a gale by the way it asserts itself over other objects. Wind, then, is about the push and the pull, about what we see when we are looking closely, and what we can predict.

There is freedom in the way the line skirts across the paper. Who is controlling this line—the hand that draws it, or the wind pushing the hand?

Zoom out and realise these are not just arbitrary lines, but lines in relation to other lines. That the lines pull themselves together. Notice how the lines arrange themselves into figures or waves or a cluster of islands or an isthmus dividing two bodies of water.

Take note of the edges of the archipelago and remember what you are looking at is the flicker of a place rather than a place in its entirety.

If the scene appears to be blurry, it is because the wind wants you to concentrate on the weather, not what the weather is pushing against.

Film Opening Technique #2: Wide, Medium, Close

Wide:

America, 1968. Winter, which means January, or February. The start of a new year.

The world is convulsing, or the world feels as if it is on the cusp of something, or the world has set the air in motion. Air begins moving and turning and twisting; air starts undoing and untying, without sympathy, preference, or regard.

It is May and there are riots in Paris. Later, the filmmaker Chris Marker will describe the student uprisings as a grin without a cat.

It is November 5th, and Richard Nixon is elected.

(In another frame, in the America of 2020, political journalists will pause mid-interview, correct themselves on their assessment, and clarify that this is not like 1968.)

Medium:

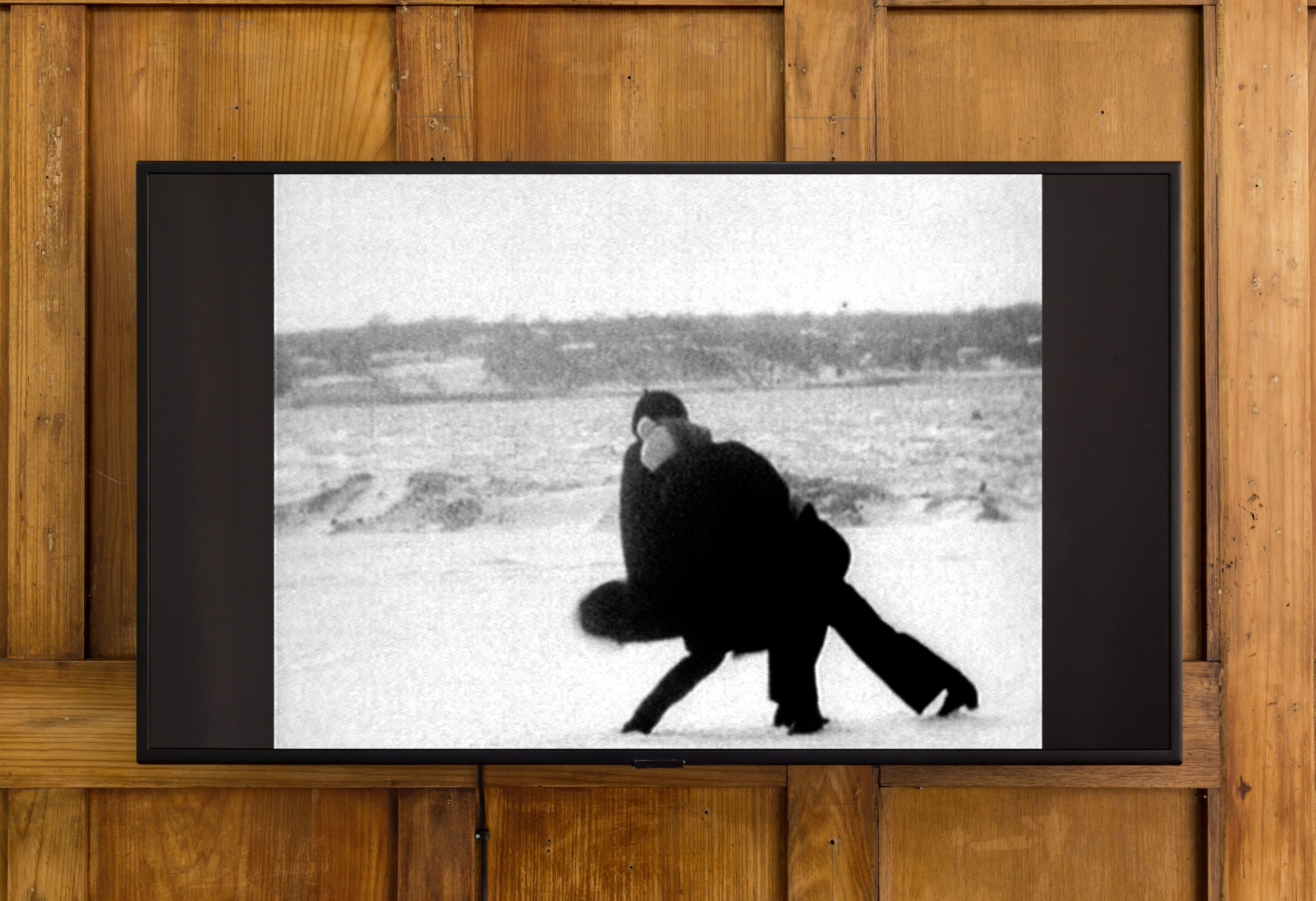

An island. An island that sits on the eastern-most part of New York State.

The setting is a strip of land next to water, which we might, in warmer times, call a beach, but for now, we will call land-covered-in-snow. There is also water, choppy and irritated, looming behind it.

This body of water is hugged by another small strip of land, which could be facing the Atlantic Ocean or the Long Island Sound. Details of the exact location are hazy. What is important is the water and the snow and the non-urbanness of the scene: no buildings, no skyscrapers, no subway cars or trains or industrial structures. The location’s proximity to a recognisable and well-known skyline nearby is irrelevant because the skyline does not appear.

The scene takes place in January or February of 1968. We know this because of the snow. The year is not important to those who are living, standing, on the snow-covered strip of land, because the year has not yet established itself as both a beginning and an end. What they are thinking about is congregating, together, on this strip of land. They are thinking about their arrangement and their movement and the position of the camera. They are thinking about being filmed.

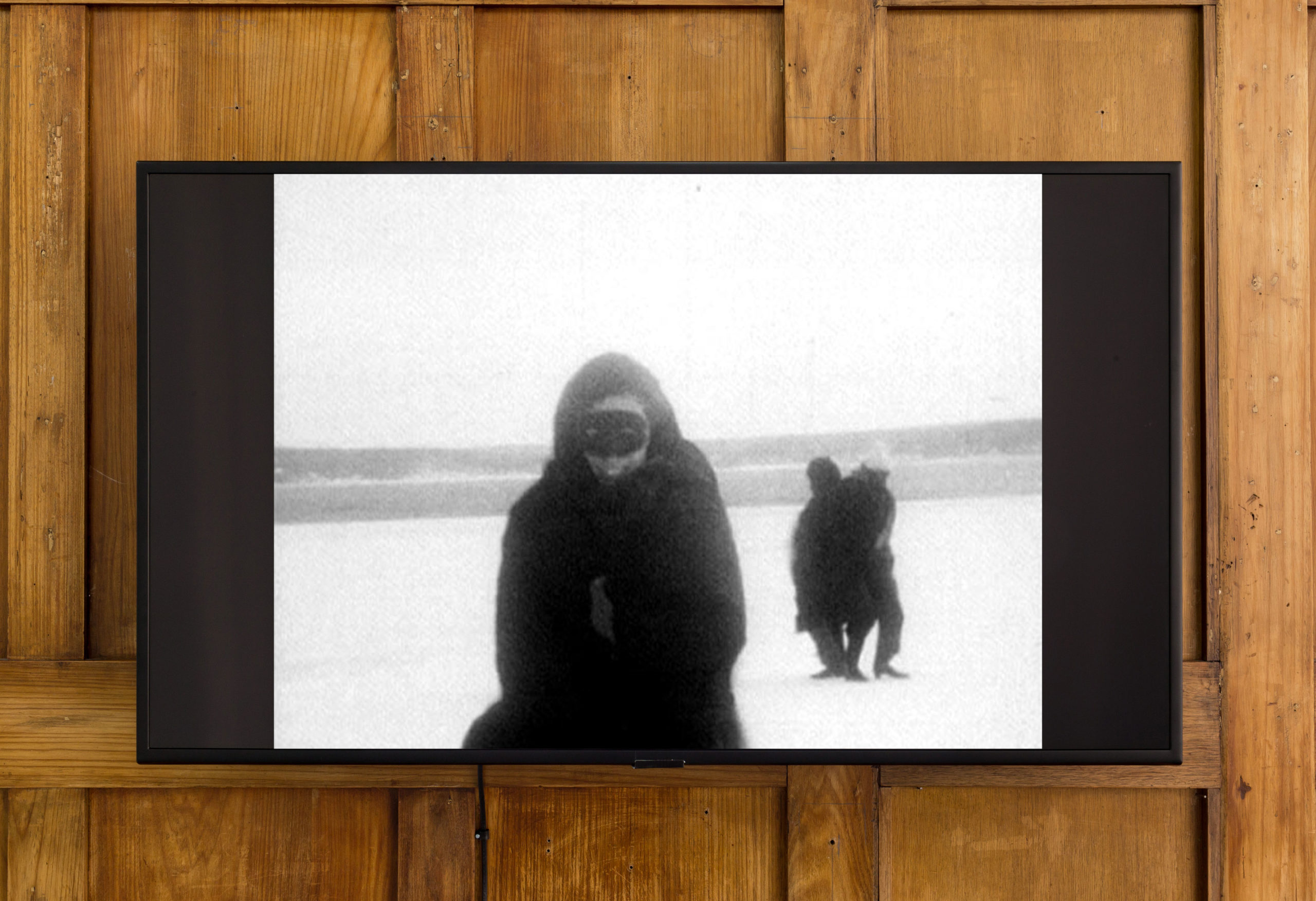

Close:

The wind is unexpected. The wind, being pushy, becomes the main event. A group of figures are making shapes out of their bodies as they stand, walk, or move, across the snow. The wind says not so fast and offers some resistance. The wind adopts the role of conductor and decides now is the time to put air in motion.

There is no audio, but we know there is laughter. You can see it every so often in the closeup of a smile, or in the way somebody bends towards the breeze like Buster Keaton. The group are shivery and cold, but they are laughing about it, calibrating themselves together. They are enjoying this persistent wind that pushes them backwards, or tips them over, all for its own private amusement.

Two figures, one tall and one short, hold hands and walk towards the water. A group of four divide themselves into two distinct pairs, lean their backs against each other and create a set of shapes that look like tented roofs.

It is the coldest day of the year.

The wind is unexpected, but the film will be called Wind nevertheless.

Film Opening Technique #3: Plunge / No Establishing Shot

oooooOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooooooooooOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooooooooooooooooooo……………………oooooooooOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooooooooooooooo……….ooooOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh smash bang crack ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooOOOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooooooo……..

Film Opening Technique #4: Mystery

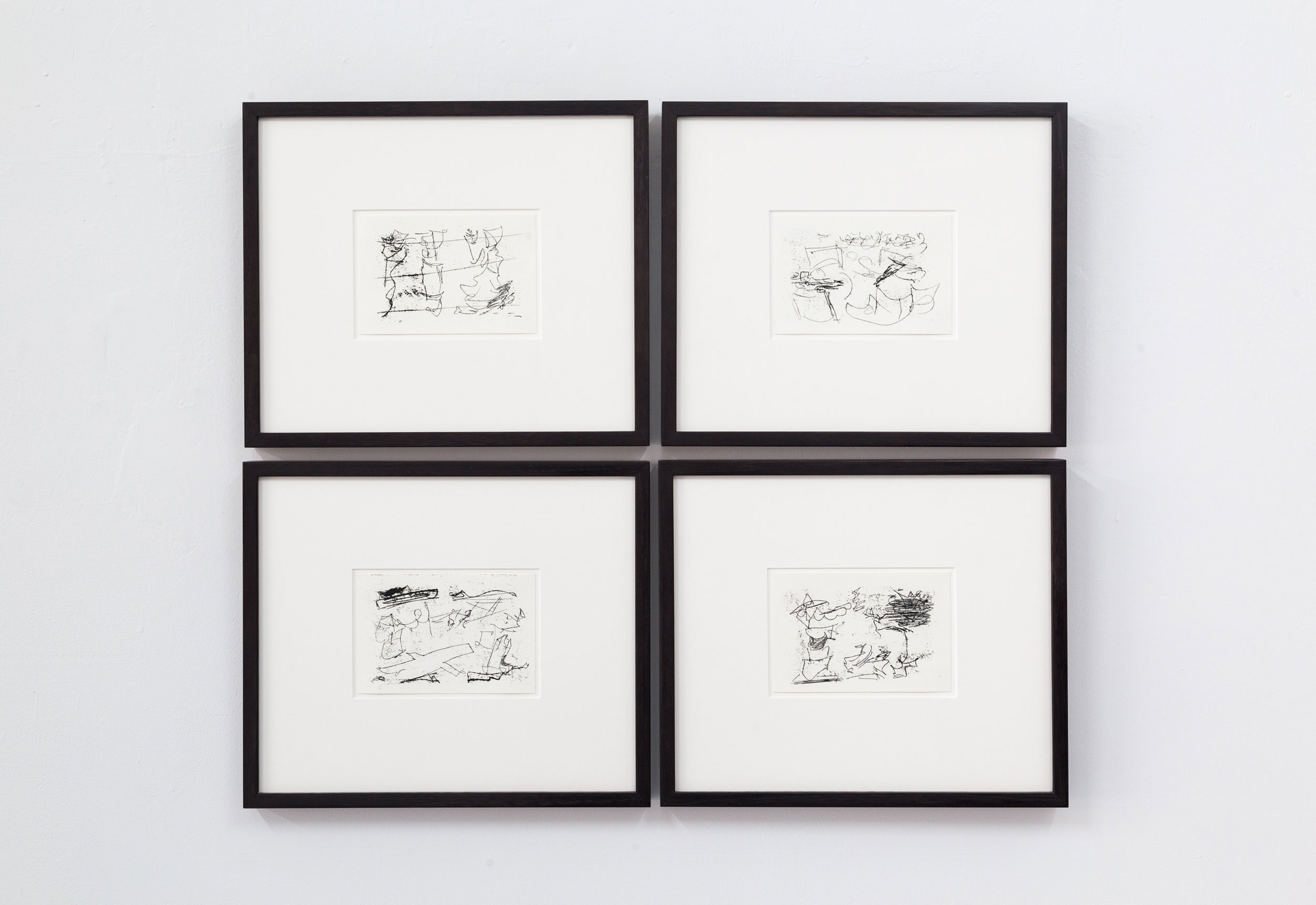

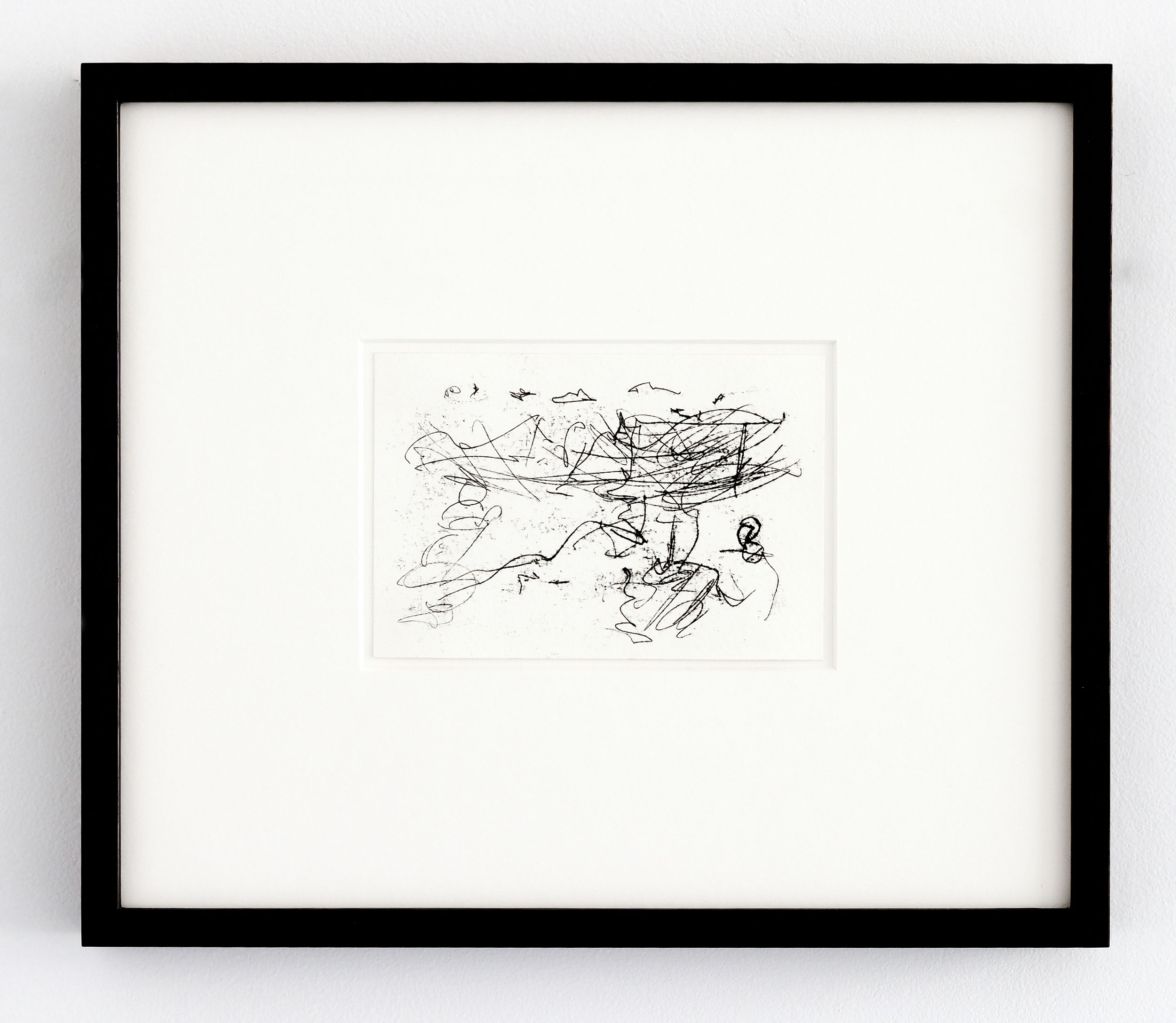

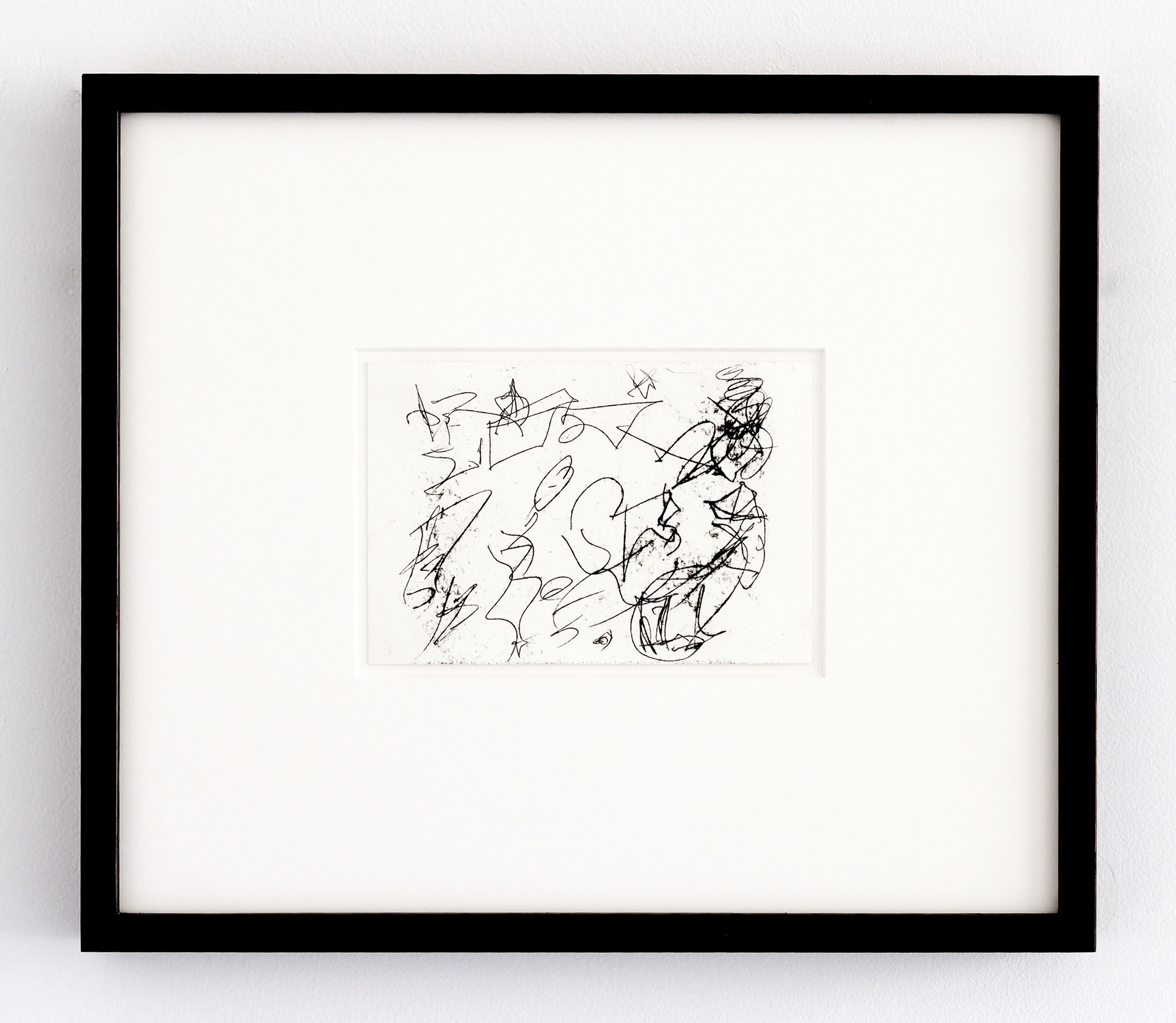

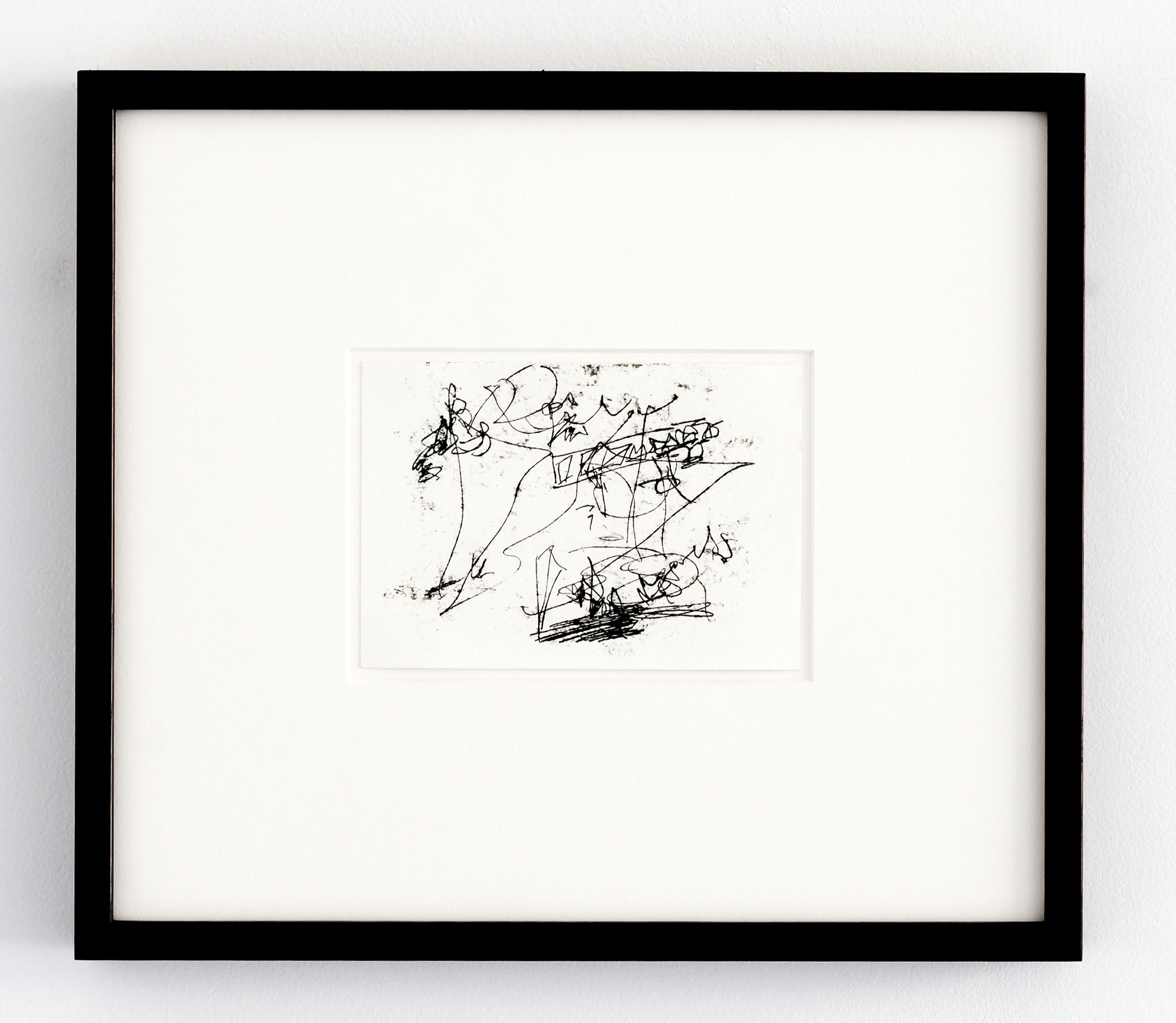

An artist sits down at a desk to work. She covers a sheet of acetate with oil paint and places it over a piece of paper.

Let’s say the paper is the size of a postcard and the oil paint covers the paper entirely. The paper remains hidden from the artist’s gaze.

She doesn’t pick up a brush or a pen but a needle, the type of fine-point needle you would use to make indentations in clay. Let’s say the artist has some idea about what mark she will make, but also that the artist is happy to give over the mark-making to the movement of her hand. On one occasion it goes skipping across the page, wanting to twirl itself, unabashed. On another, it is slow, more reticent, and shy.

The needle scratches into the oil, carving out an image.

We cannot see the paper.

We cannot see the drawing.

Film Opening Technique #5: Fragments, Parts, Things

A flash or a glint, on film, something reflective, hanging suspended around the neck of one of the dancers. The work is a mirror.

1968: the year that shattered America.

A gale is defined as a surface wind speed of 34-40 knots.

The instrument for measuring wind is called a sonic anemometer. Its name is derived from anemos—the Greek word for wind.

January 1968 is Long Island’s seventh coldest month on record.

A hand may dance just as a body may dance, but wind causes everything to dance.

What is certain is that our response to a gale is always the same: we lean into it and address it, rather than tipping back.

Wind speed is affected by obstacles in the vicinity.

Unruly overcoats and jackets, refusing to stay buttoned but still caught on shoulders and elbows, waving at the camera like flags.

Wind as a noun is air in motion, but wind as a verb is to turn, twist, plait, curl, brandish, or swing. To set a clock to the correct time. To lose one’s breath; to have no air in the lungs, in most instances, because one has been punched in the stomach. To gain a second wind.

Jill Johnston (1968): words are pictures are sounds are sights are touch are smell are the altogether forever. The artists are rampaging through the graveyards of the file cabinets to throw the alphabetized cards into the beautiful chaos of the altogether from whence they were so painfully extracted to make a mess called civilisation.

Learn how to consider wind differently, especially in the moments it has nothing to cling to.

If you stand firm when facing a breeze, it feels as if the current is only interested in you.

—Naomi Riddle, 2021

Author’s note:

Opening film techniques taken from ‘Episode 1’ of Mark Cousin’s Women Make Film (2018), narrated by Tilda Swinton.

Naomi Riddle is the founding editor of Running Dog. She has written for Guernica Magazine, Oberon, Blonde Art Books, Sydney Review of Books, Das Platforms Online and HTMLgiant among others. Naomi is currently studying a Masters of International Relations at the University of Sydney, specialising in US Foreign Policy. Naomi holds a PhD in Australian Literature from the University of New South Wales (2015) and her work on the Australian author Elizabeth Harrower has been published in Southerly.

Joan Jonas (b. 1936, USA) is an acclaimed multi-media performance artist, and a major figure in video art. From her seminal performance-based exercises of the 1970s to her later televisual narratives, Jonas engages in an elusive theatrical portrayal of female identity. Employing an idiosyncratic vocabulary of ritualized gesture and symbolic objects that include masks, mirrors, and costuming, she explores the self and the body through layers of meaning.

Mary MacDougall (b. 1983, Australia) is interested in the physicality of paint, subjects in transition and questions of perspective. She works with glass, ceramics and image archives. Forms in her work sometimes appear ancient and quiet, while at other times like super-heated rock, flowing and coagulating.

With thanks to Karl McCool.

Joan Jonas, Wind, 1968 appears courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix, New York.