I would like to share a fantasy that I have with you all. In this fantasy, I am sick and plagued with something as yet unknown to modern medicine, and I can no longer participate in society. At first it is a welcome escape from life, but then the sickness becomes life and I need to escape again. That’s what believing in a higher power is for, so naturally I ask them: What is the matter with me? My eyes are closed in anticipation of an answer. At first, nothing, just a few remnant shapes from the day and, not unentertained, I watch them become each other for a while. Then suddenly, God responds, with some image whose spiritual density is immediately obvious, a plastic bag, something like that. I realise at once that I am not alone in my struggle. In fact, there is something even greater than me, suffering an even greater pain. Of course! It is the very economic system that we live under, she is languishing next to me in my bed.

I feel that, over the years, I have been tricked into seeing capitalism not as a Being with the capacity to suffer, a more than human assemblage equally deserving of non-anthropomorphising empathy as the rather more fashionable slime mould or rhizomes, but as an insensate set of rules working towards a certain outcome. I became suspicious of this account once I realised that my sense of the outcome seemed to change as my luck and income did. If ever I was doing badly, I thought: We are all hurtling towards doom. Then I would be doing a lot better, like one or two figures better, and I would think: Everything according to plan. This is the greatest time to be alive and it is only getting more great. Then it would be revealed to me that thinking such things is a low interest rate phenomenon. My life would get a little worse but not as bad as before and I’d become quite ambivalent about the whole thing: Is it both at once? We are hurtling towards doom, yes, but it’s simply a matter of death and rebirth? Just a few more civilisational collapses and up only after that?

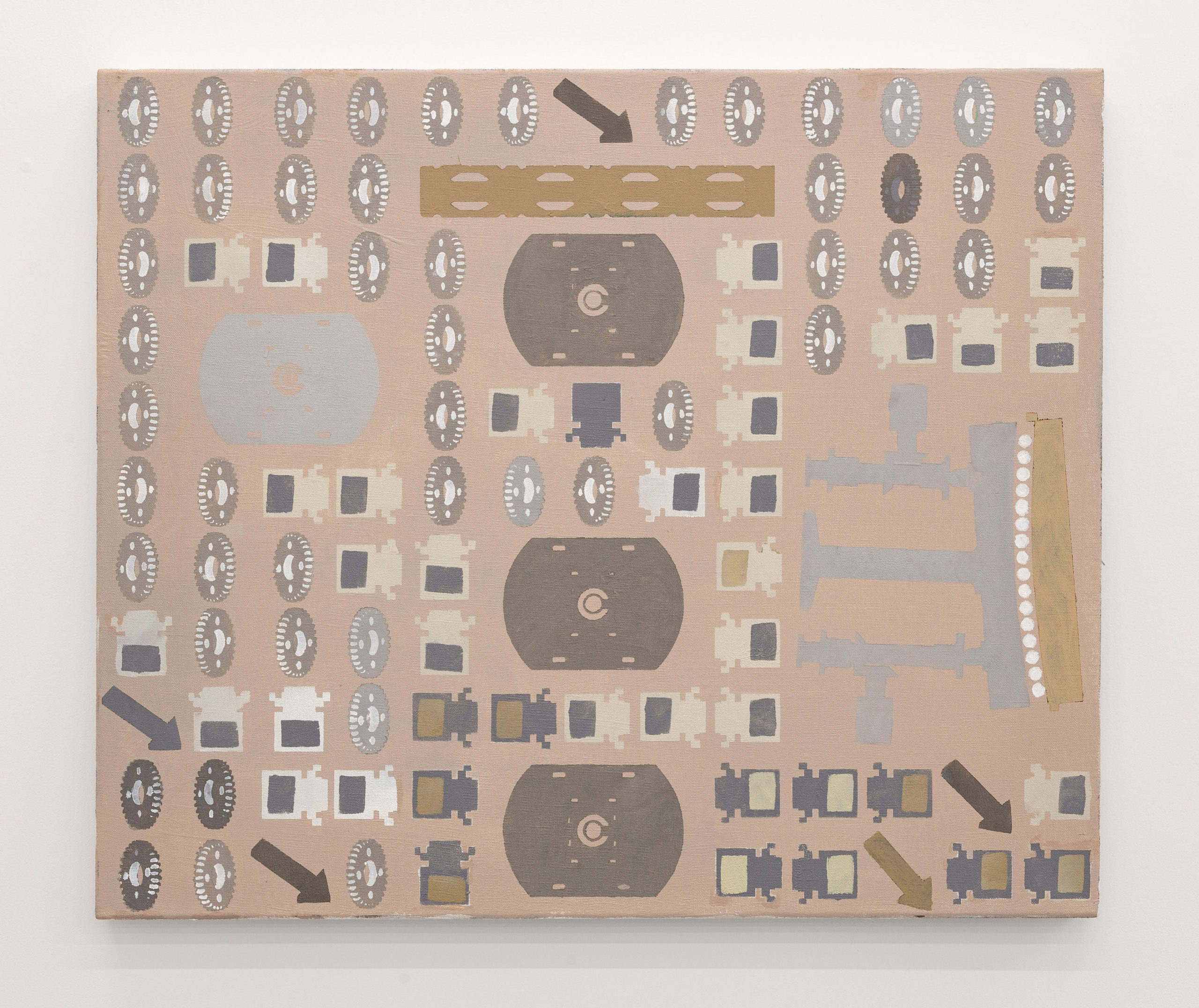

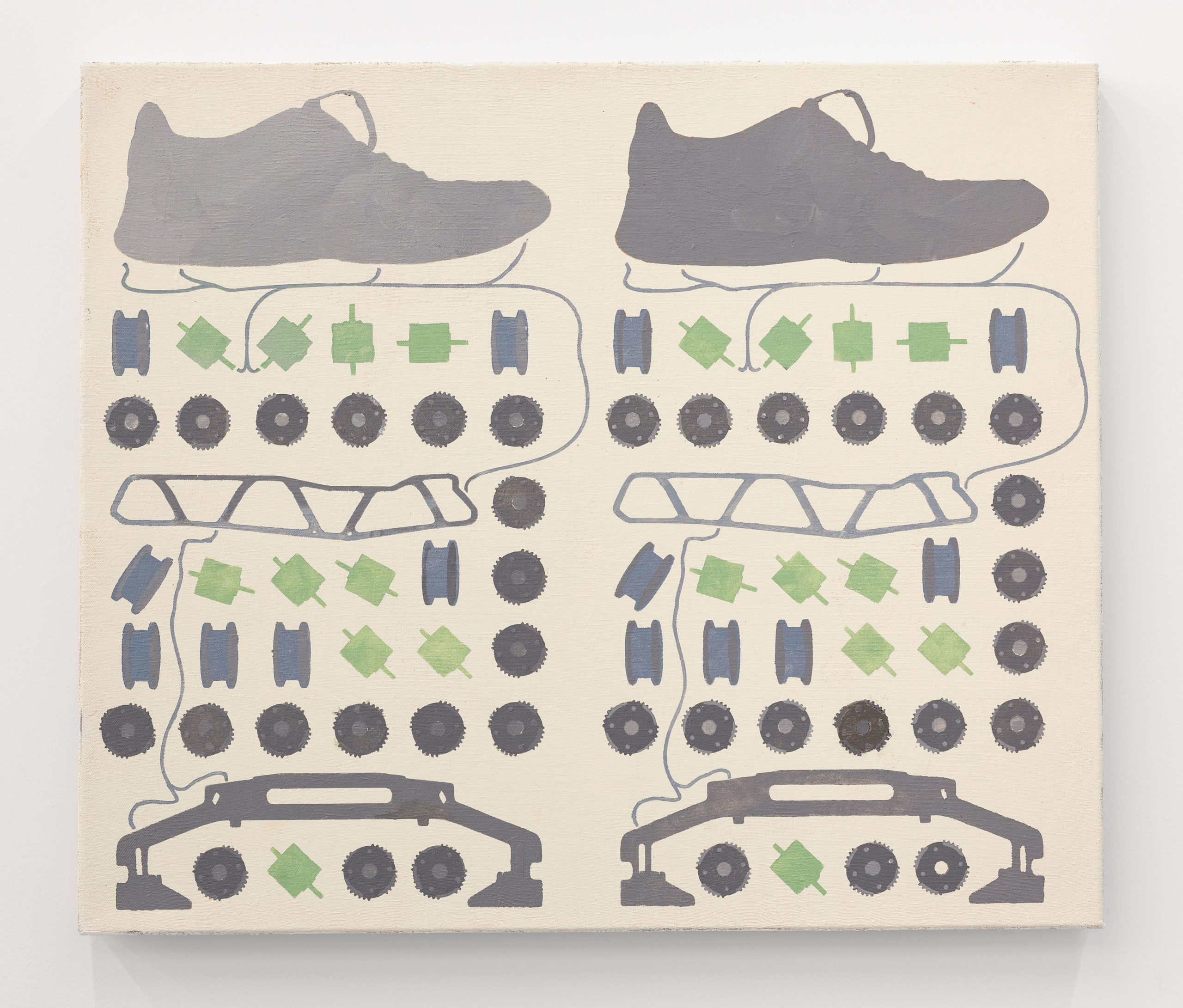

The optical illusion of progress, whether good, bad, or cyclical, hinges on the conflation of motion with direction. And there is certainly a lot of movement, a lot of exertion, and this is precisely the pain that she is suffering. Things from the outside ripped towards the inside, things moving faster, with greater intensity, new limbs being born, dying parts cast off and then revivified to form new and terrible combinations, patterns becoming increasingly and sickeningly granular. I like to visualise her as an old testament angel, hovering forever in the same spot, treading air like water, wings and eyes moving in constant and frenzied reconfiguration like a self-animating Rubik’s cube.

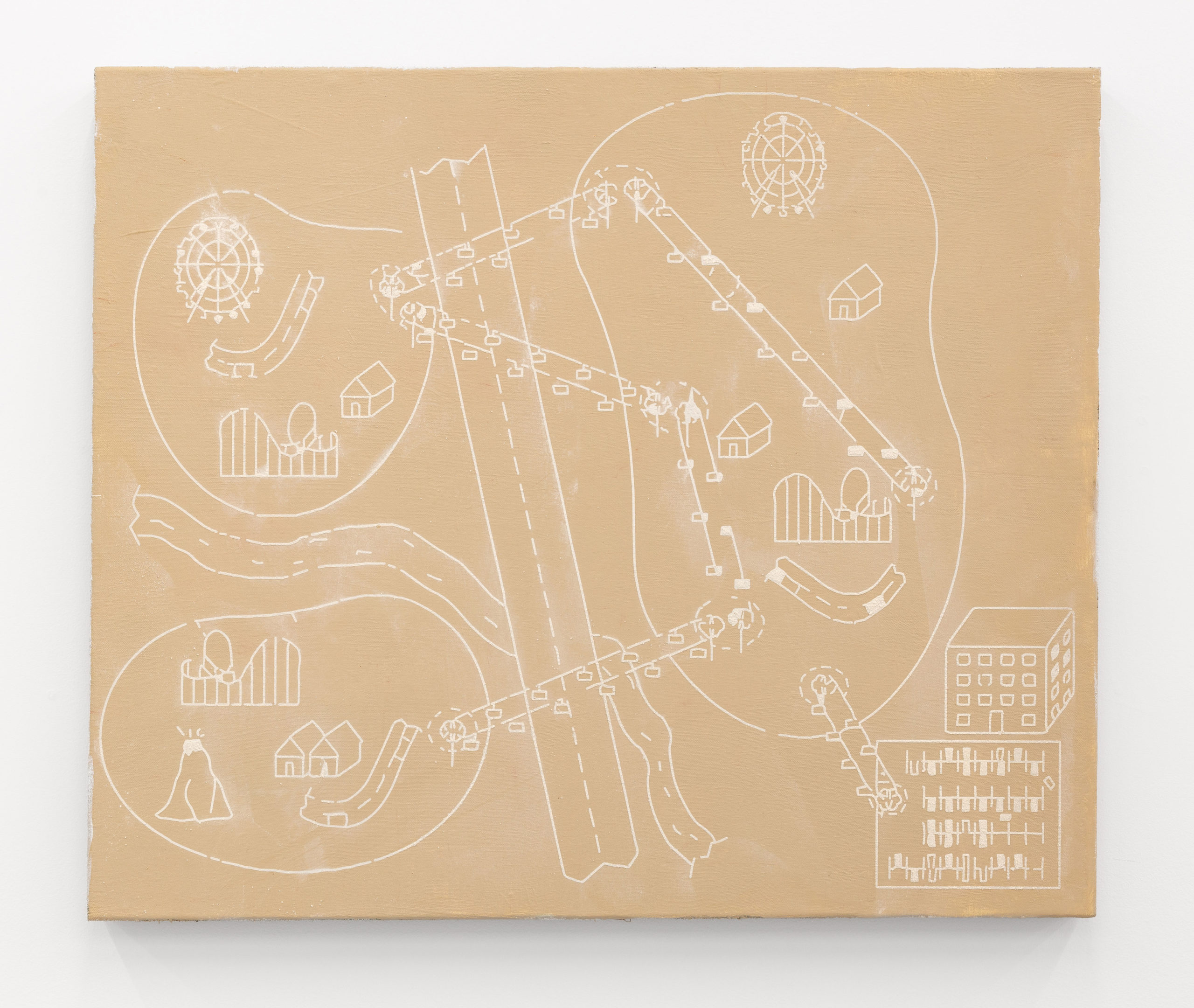

Perpetual motion without progress, acceleration without telos, where else do we find that? Victims of dancing plagues that broke out across northern Europe in the Middle Ages would have known just how it felt to be compelled into constant, non-purposive motion. In the same period, inventors were fascinated by the possible impossibility of a perpetual motion machine that could turn forever. Diagrams for these machines looked, in turn, similar to the mechanistic representations of the wheel of fortune, another important secular icon of the time, spinning forever to assign everyone ever their respective fates but never moving from its own position. Some wheels of fortune were constructed physically, big enough for humans to ride on, the mechanism by which they turned concealed to give the impression that God was the one who moved the wheel.

In all these cases, we run up against the annoying limitations of thermodynamic laws, eventually the energy powering our movement in place will run out. We will dance until exhaustion, the perpetual motion machine will only turn forever if we give it a little nudge once in a while, the wheel of fortune carries us round only until the assistant inside tires of cranking it by hand. These are all sweet human approximations of the universe itself, which does not progress, only expands and accelerates in its expansion, supposedly forever, even after a possible heat death. Immortality is so torturous that way. Capitalism, well bounded by thermodynamics, has a slightly different curse: A kind of technical immortality where she can always die, yet never loses the will to live, forced to use all kinds of tricks to pull back just before the brink of death by malnourishment. How? In a stunning evolutionary gesture, she makes her own sickness edible.

For centuries, whey was cast into the oceans, dumped into rivers and sprayed onto fields, cheesemakers of yore behaving like the angels of Revelation’s seven bowls: “Then the first angel poured out his bowl on the land, and ugly and painful sores broke out on the people…The second angel poured out his bowl on the sea, and it turned into blood like that of a dead man…Finally, the third angel poured out his bowl on the rivers and springs of water, turning them into blood”. This pollutant, more than a hundred times more powerful than human sewage, was also poured into municipal waste systems for a time as towns and dairy industries grew in tandem. There already, life sprang from the effluent, as the whey fed massive algal blooms. With just a little more inquiry into the nature of protein, we recovered the Hippocratic foreknowledge of whey’s nourishing properties and found that it could feed us too. In ancient times, whey was prescribed to those afflicted with sepsis, or applied to sores on the skin. Today it casts its miracle much wider. Whey feeds the strong and the meek, the sick and dying. It is in war, as one of the most common supplements used by military personnel, and in prisons, bought and sold by inmates, or force-fed to hunger-striking prisoners via nasal intubation. Now we must contend with plastic turning the oceans to blood like that of a dead man. I see no reason to be afraid, however. It’s thought that plastic can be turned to protein powder too.

—Joanna Pope, 2023

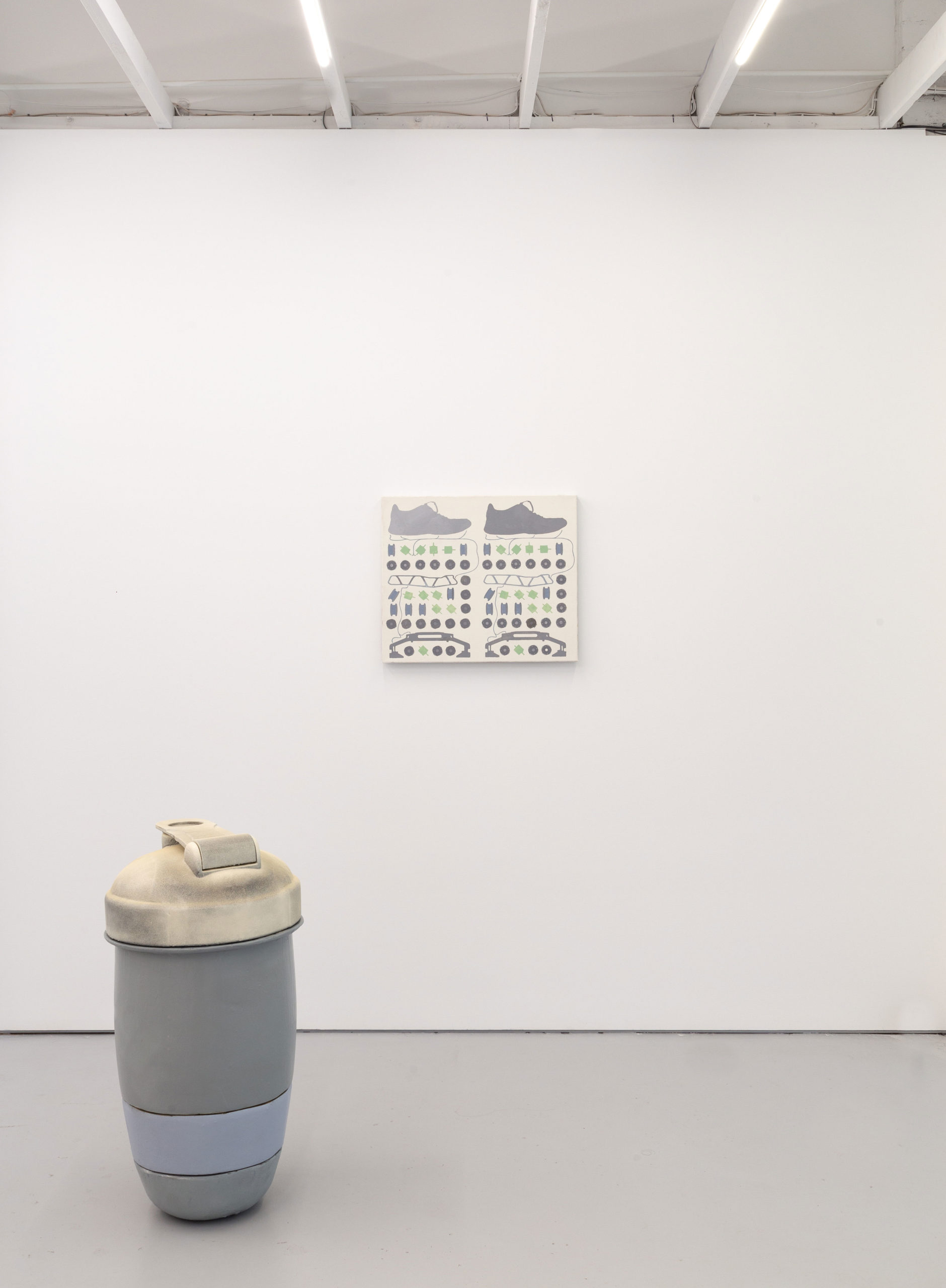

Jordan Halsall is an artist based in Naarm/Melbourne. His work is an amalgamation of disruptive practices and technological change journeying through optimisation, growth and exit. His practice centers around bridging an interest into the connections between the prosumer and built environment.

Halsall co-directs the gallery Savage Garden and is a past board member of TCB Art inc. Selected solo exhibitions include Terrarium, Neo Gracie, Melbourne (2023); Have you seen my Video? ReadingRoom, Melbourne (2022); Walkaway, Haydens, Melbourne (2021); Fertilizer, Conners Conners, Melbourne (2020); and Task Executor, MUMA Science Gallery, Melbourne (2020).