A ROCK IN THE OCEAN

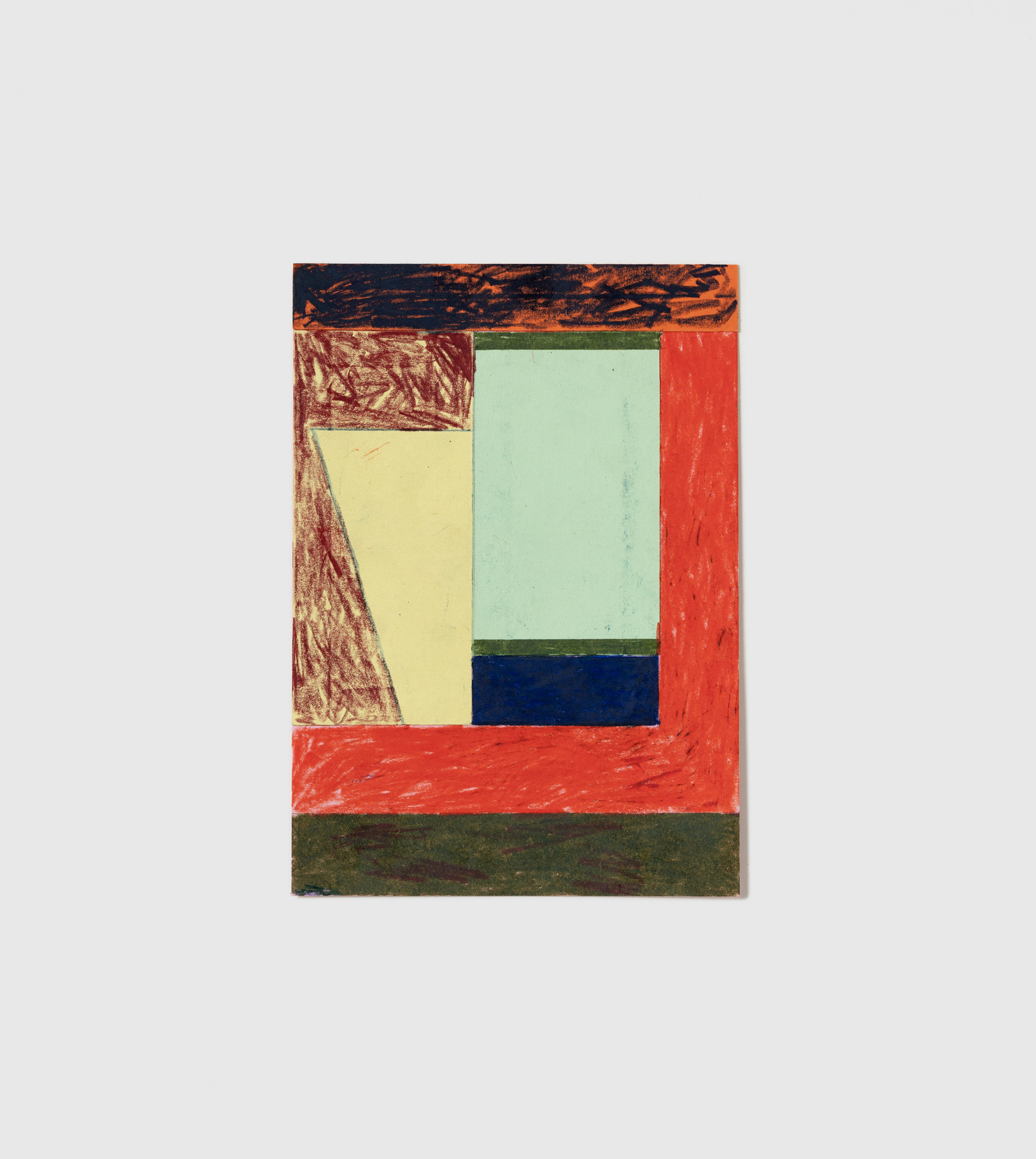

To me, Mark’s works, as both physical objects and as the meaningful outcome of thoughtfully engaged processes, refer to what begins to be possible when someone holds contradictory and sometimes opposite forces in a singular tensional structure that manages to balance itself while you live with it.

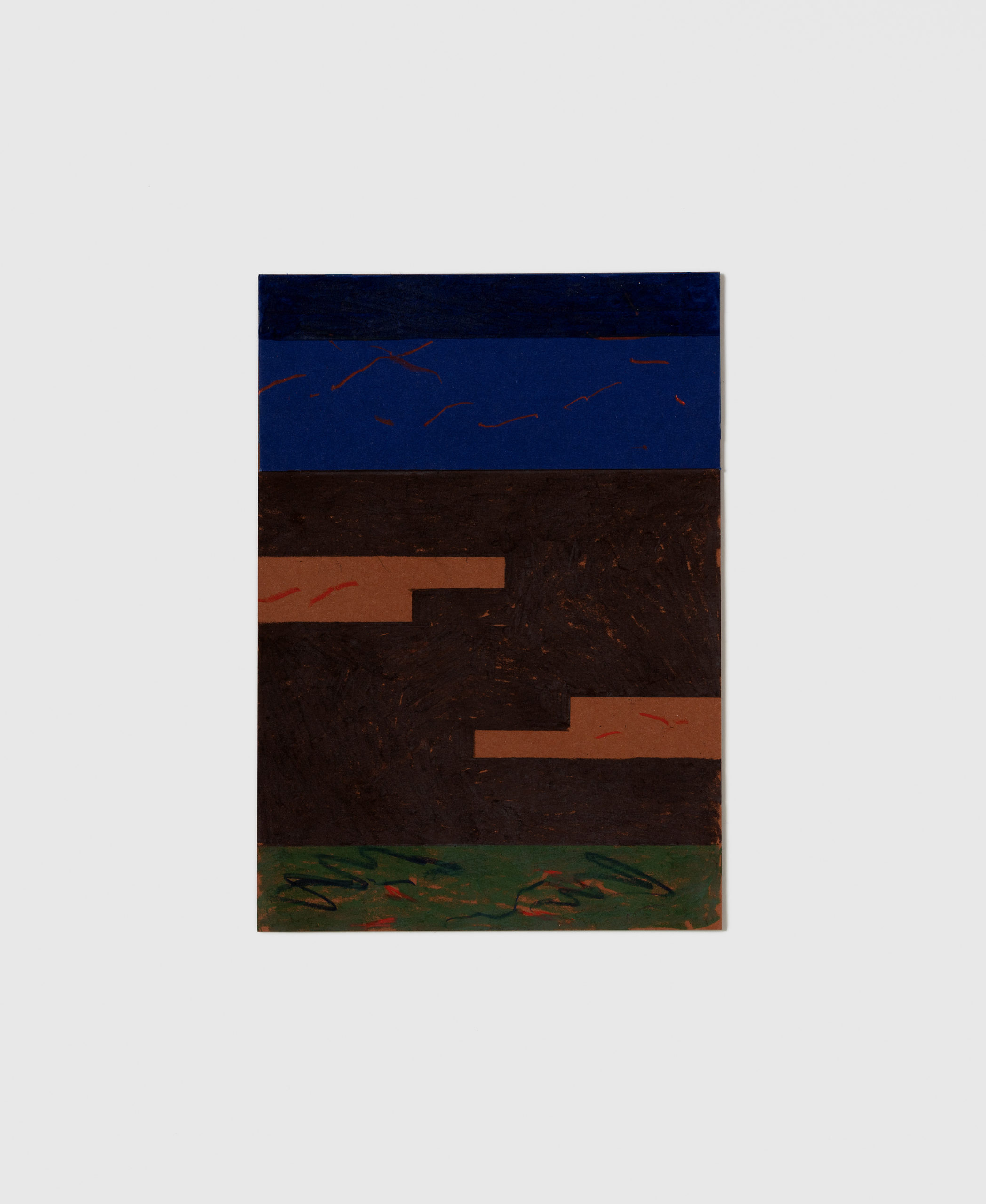

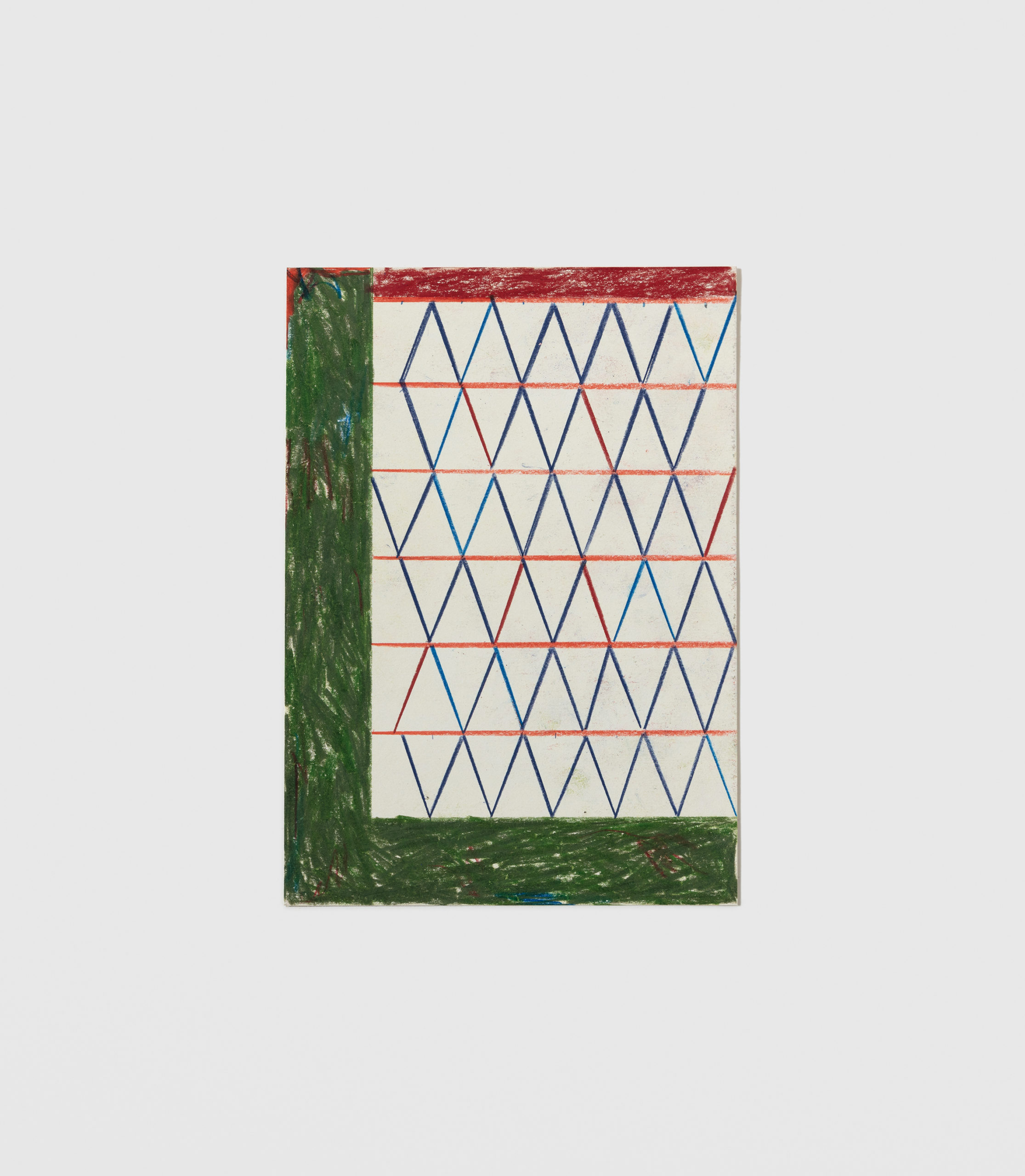

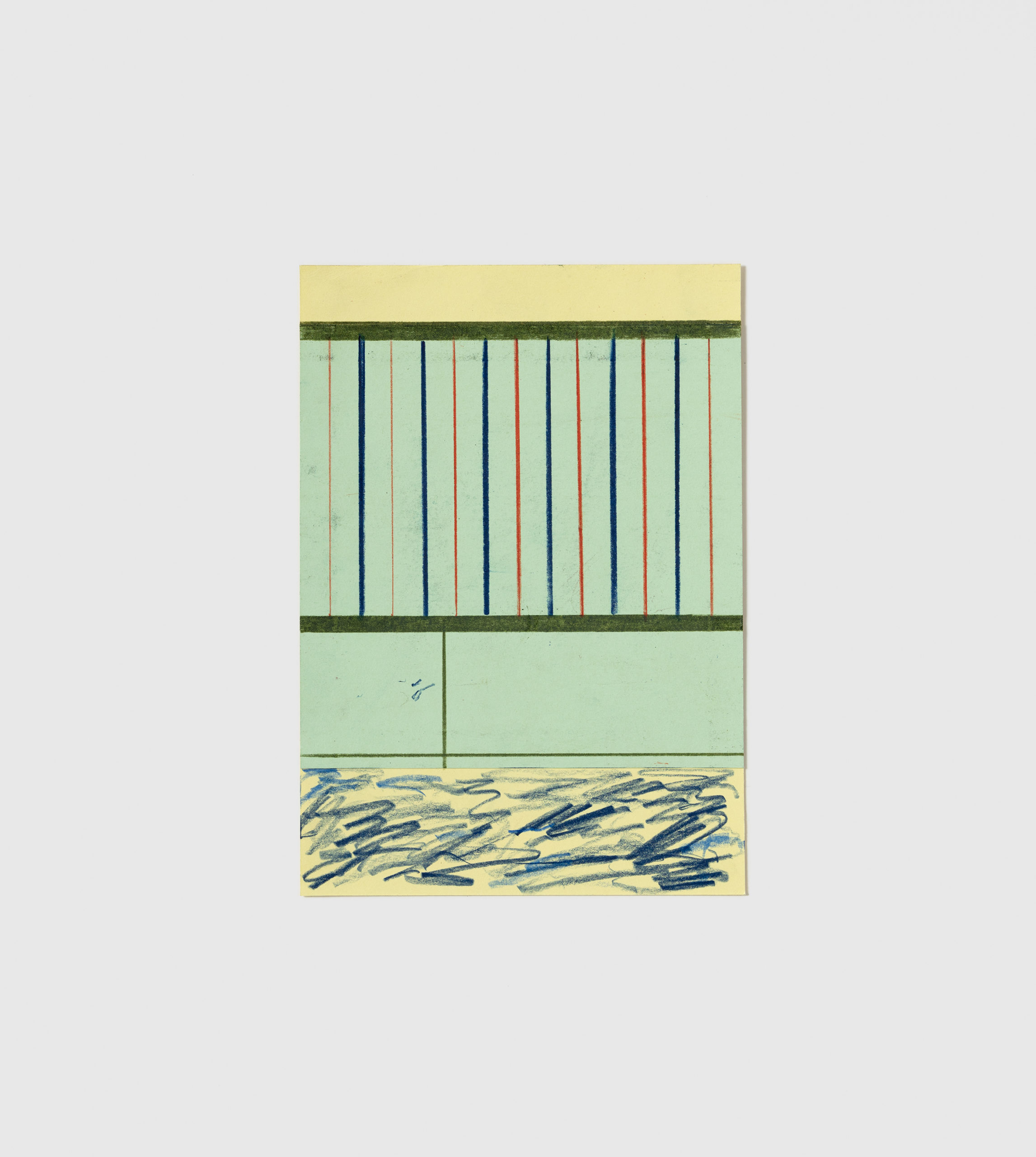

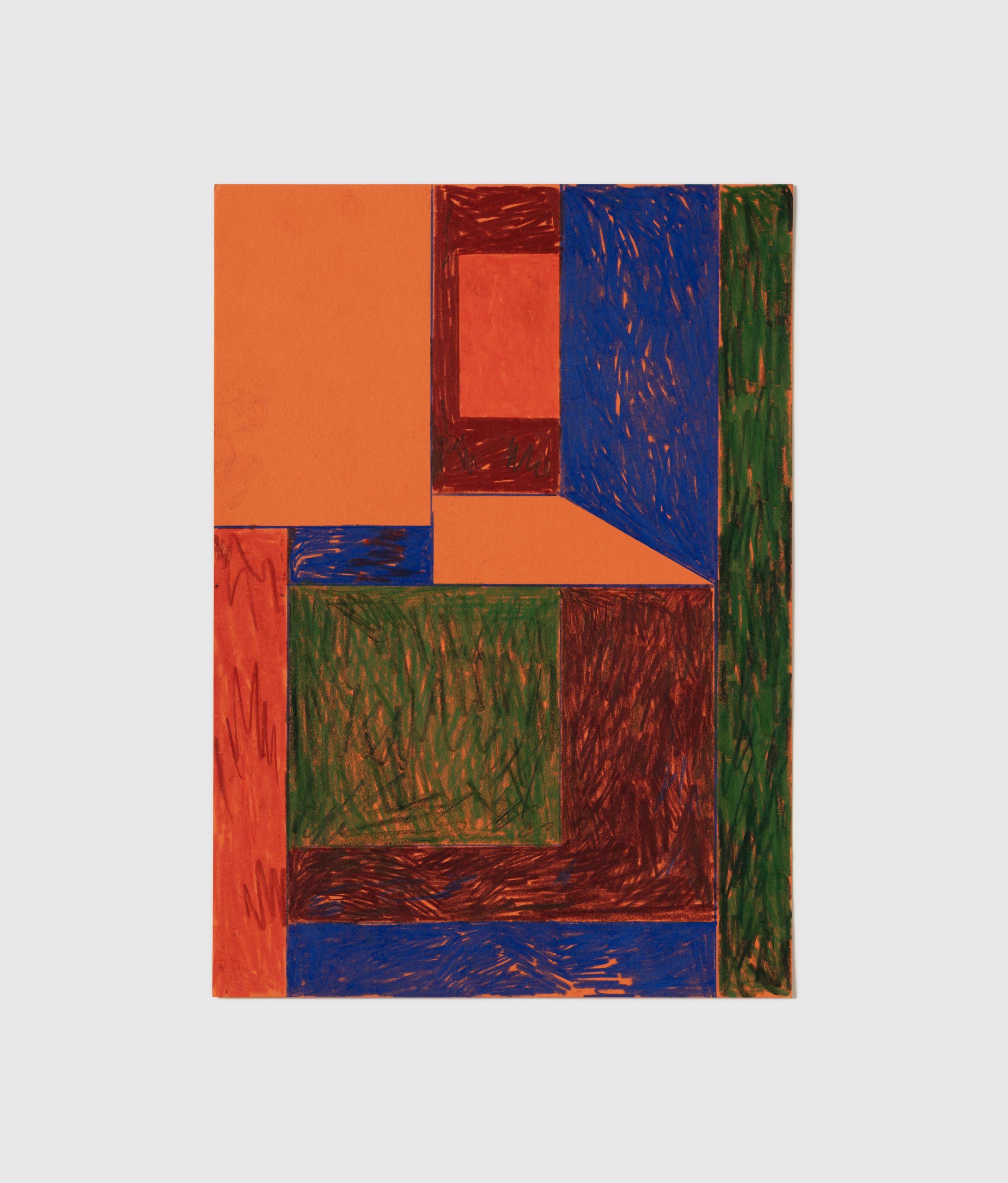

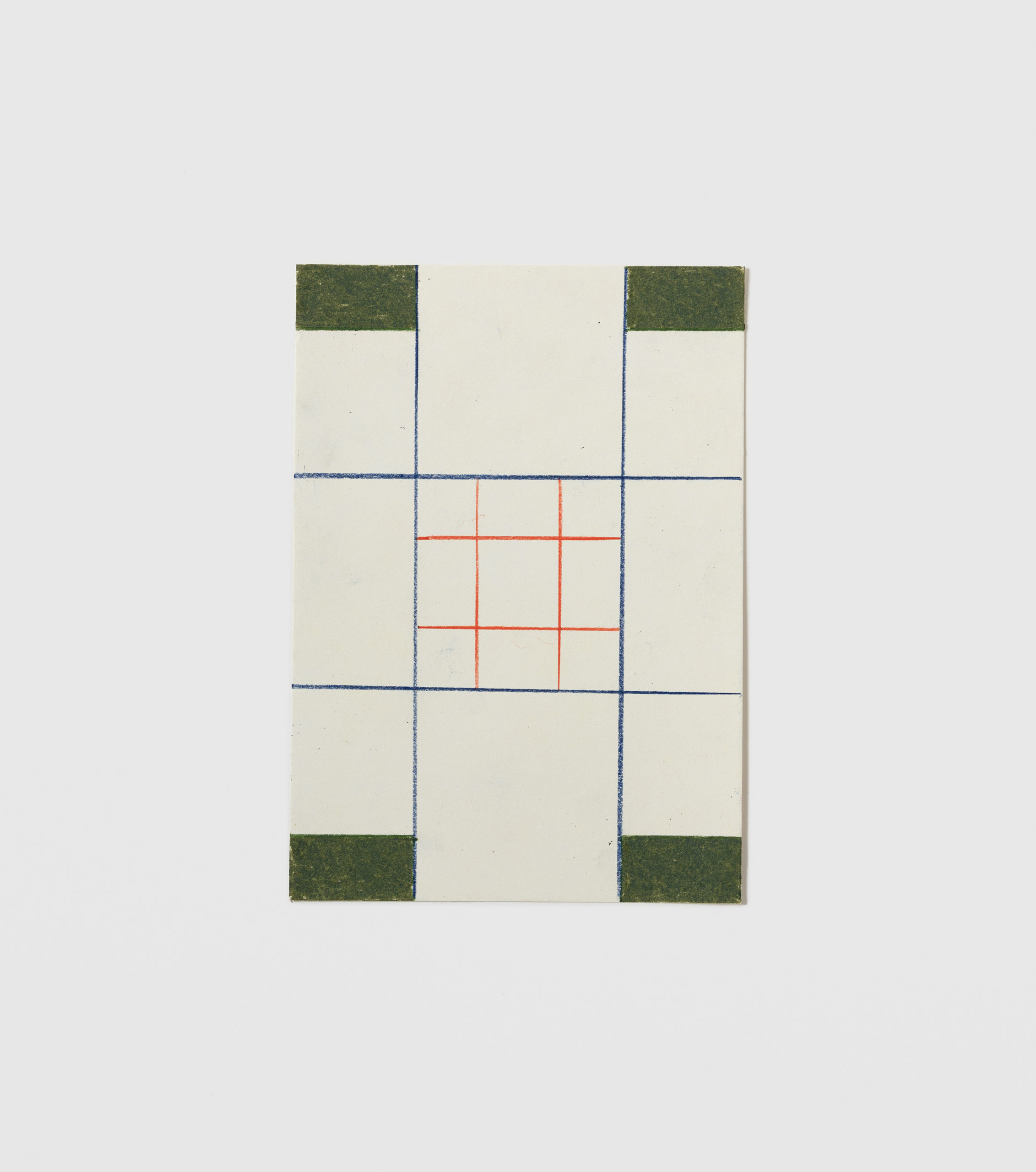

It relies on a muscular economy, but it’s also ever so subtle. The line wobbles sometimes, it blurs, and then there are obviously very straight lines; there’s walking — ways of treading those lines. Before, I said there’s a bit of dancing in the dark. Its place is on axes in between things and as part of a continuum of prior and future actions and movements. There are so many ways it makes me think about the two ends of a horseshoe meeting — the uncanny loss of what appeared at first to be strictly opposite or opposing. Most importantly I don’t think I can separate Mark’s work from Mark, working — and I wouldn’t want to.

I believe the ‘meaning’ of Mark’s work resides equally in the action and processes engaged in its production as much as any formal visual qualities or analysis born of those. As crucial as Form is to these works, so is the process of playing with Form until things look and feel right — there’s an intuitive underpinning to it all.

They aren’t action paintings — but they are paintings whose meaning is bound to actions repeated to make up the processes by which they’re produced.

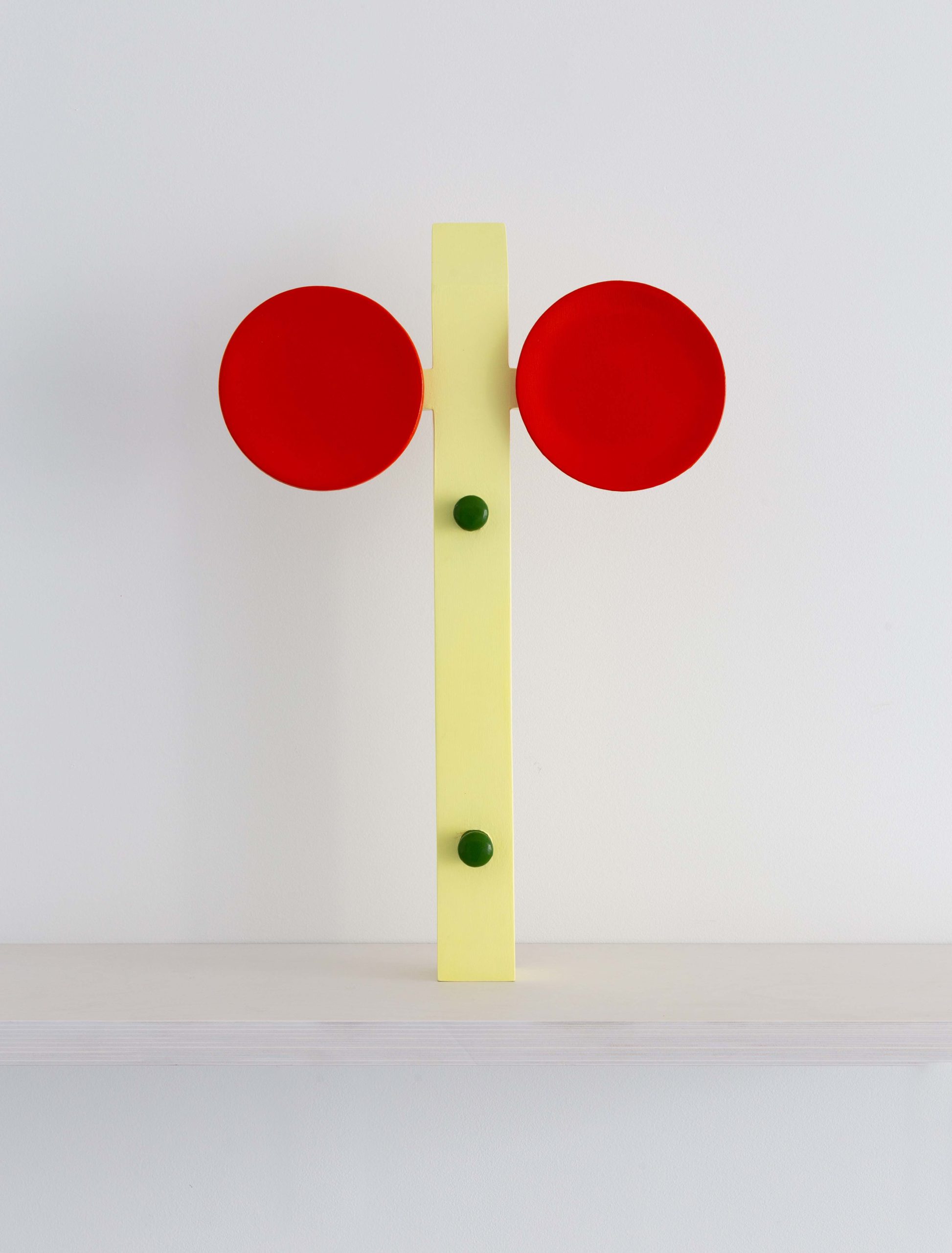

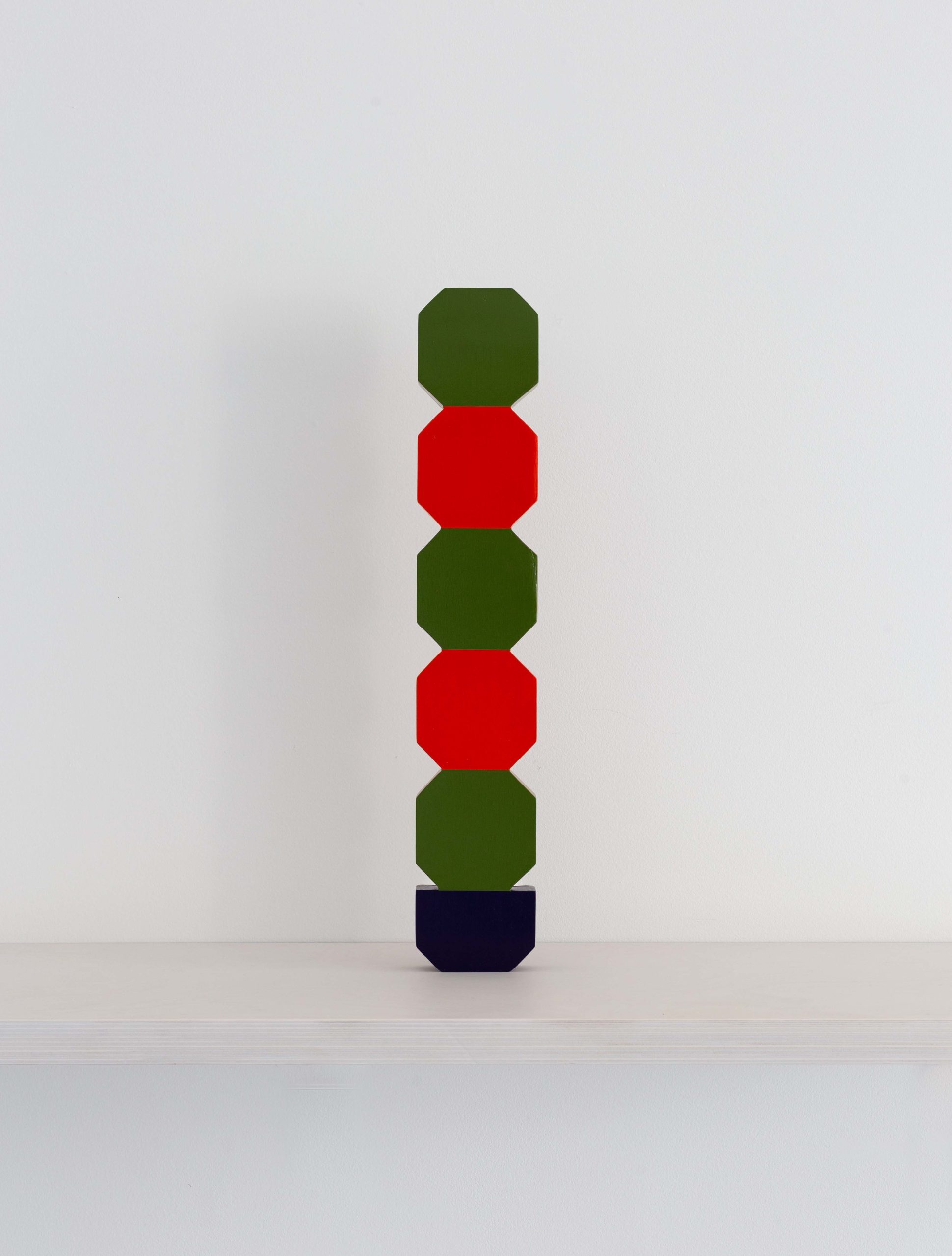

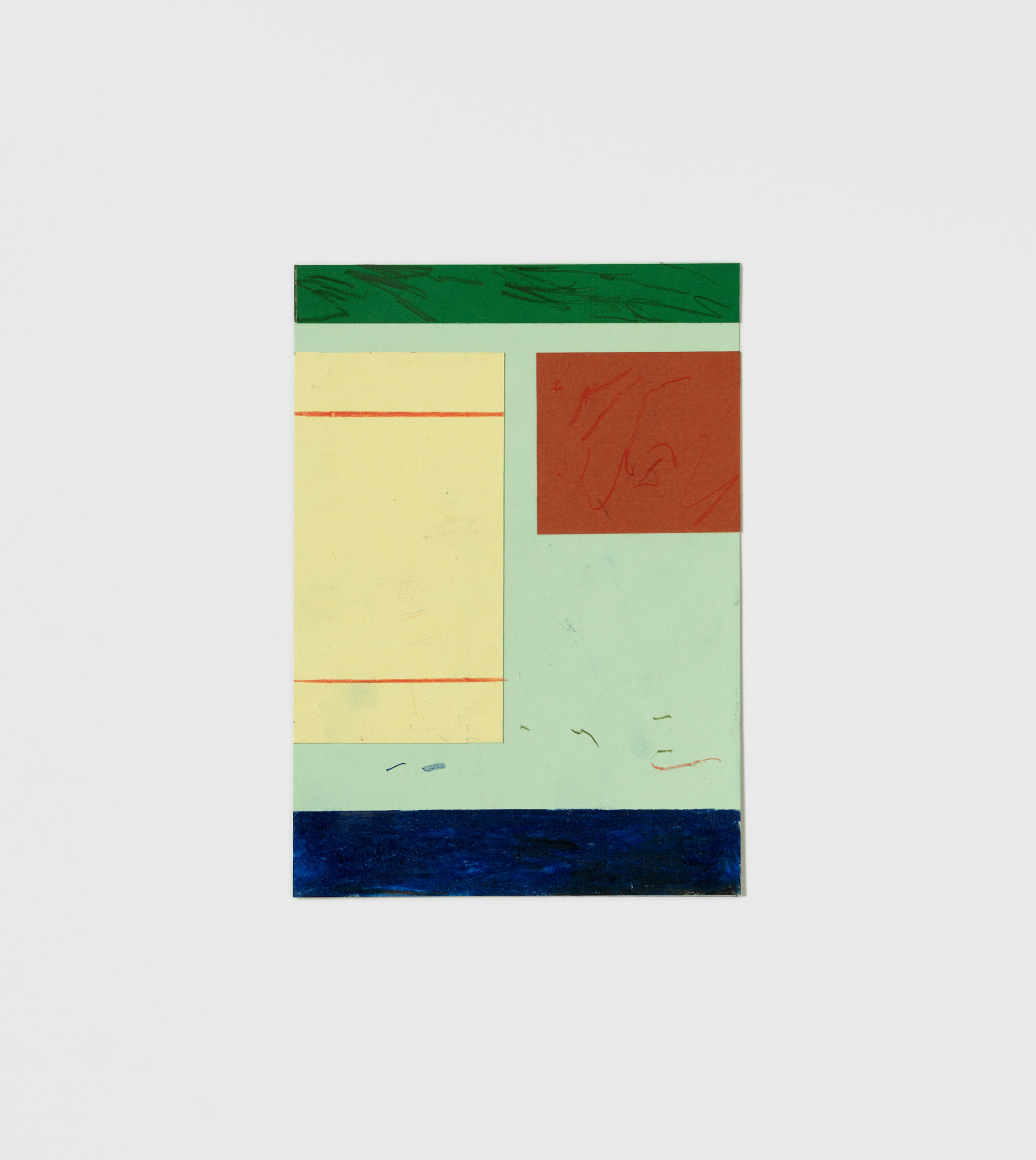

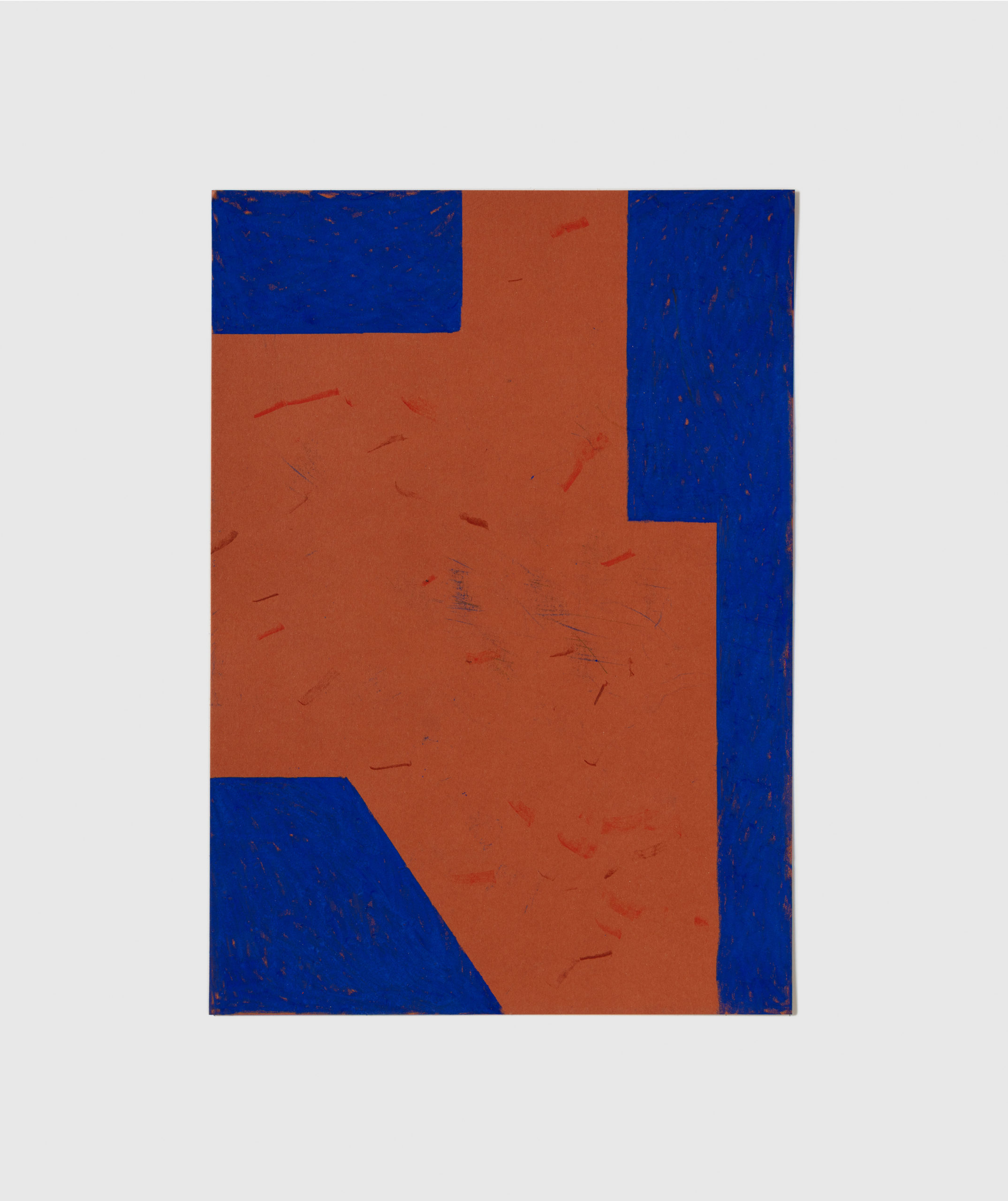

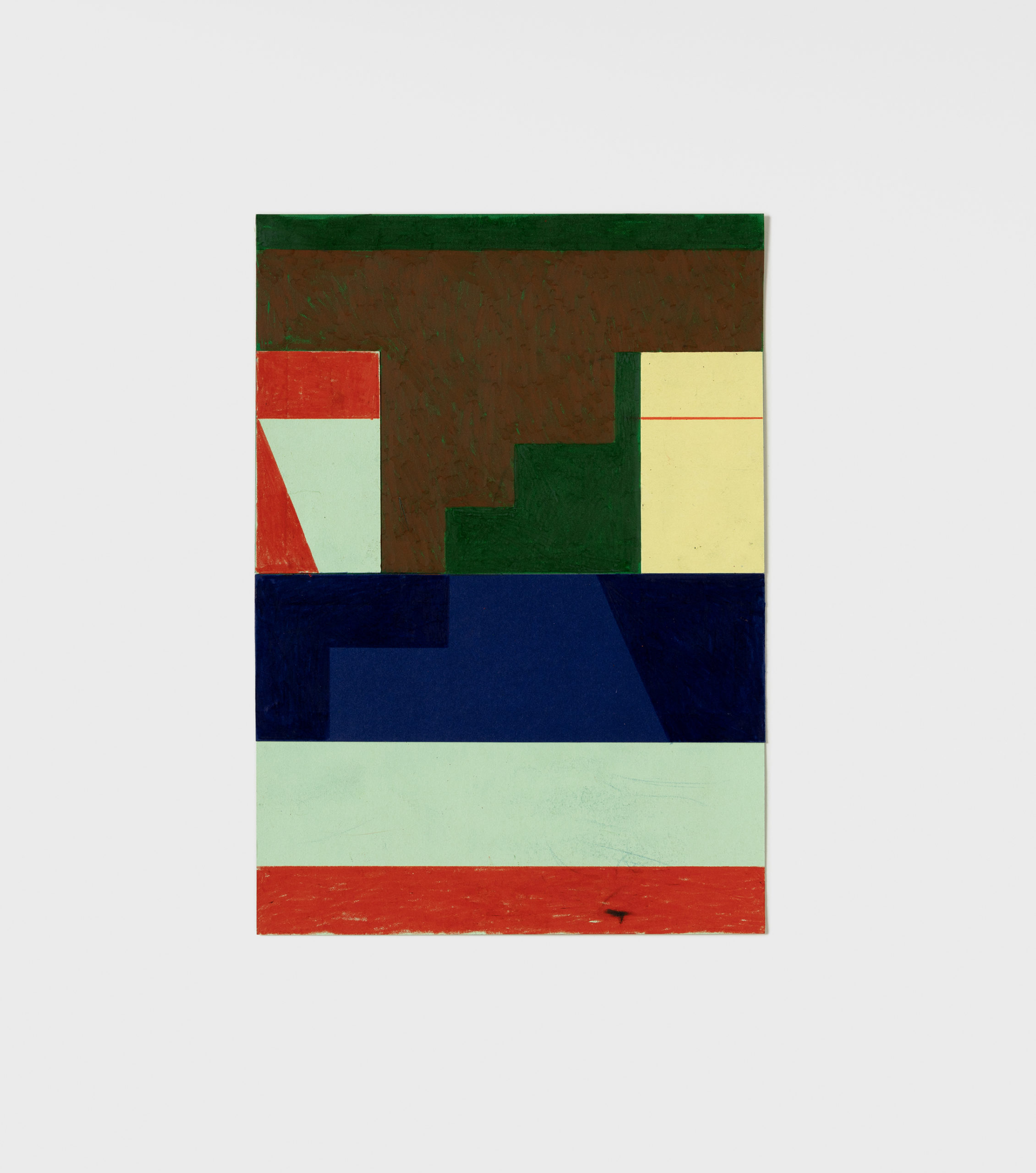

All the works in Fruit Fields are both about and a product of finding balance. This is obvious in a strictly visual sense but also goes to the heart of everything about them being made, to the extent that what they mean is implicitly about both.

I want to describe the space of this meaning being generated as a diagrammatic, multi-dimensional onomatopoeia and though it may not strictly make sense I hope you can feel what I mean.

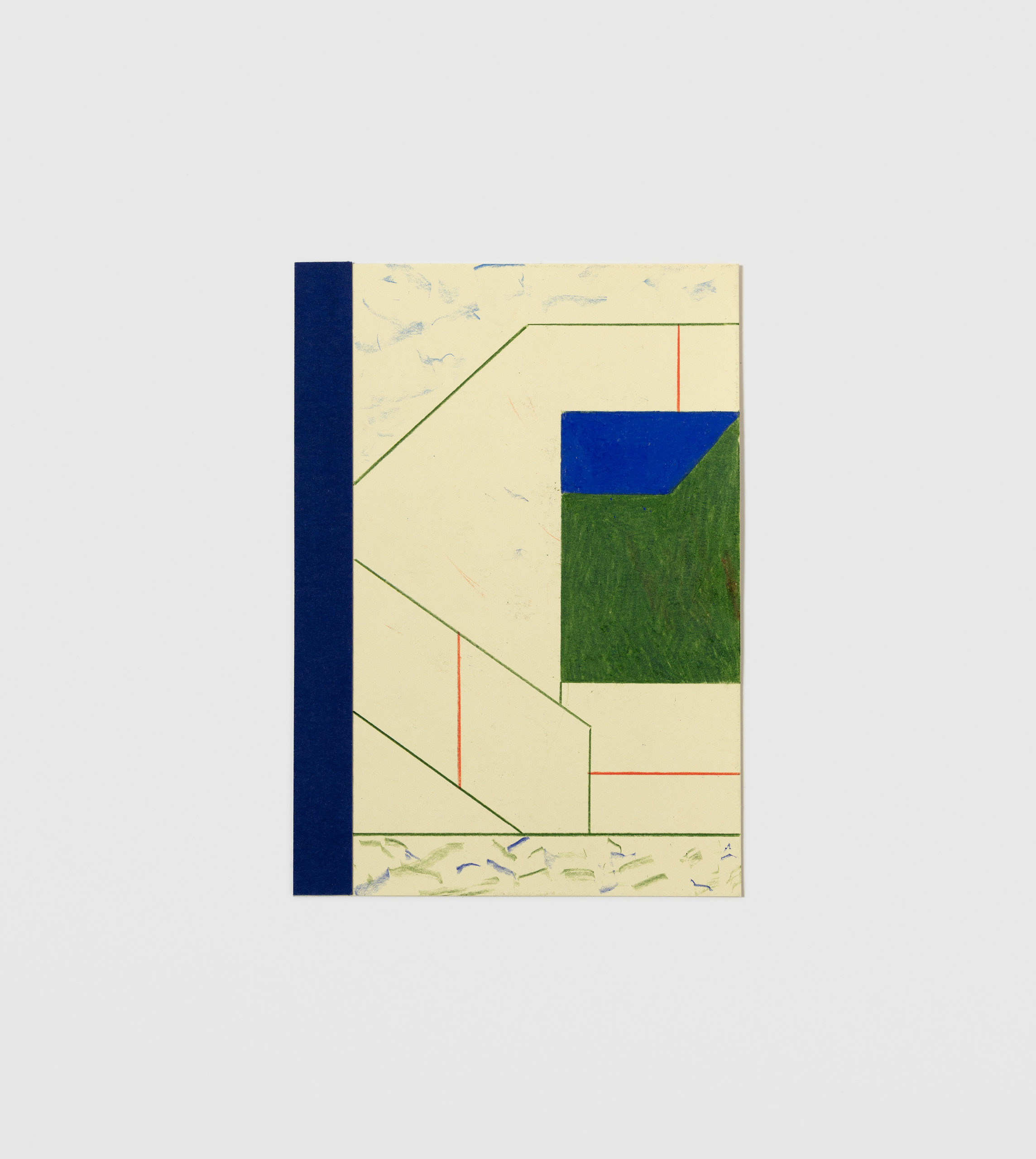

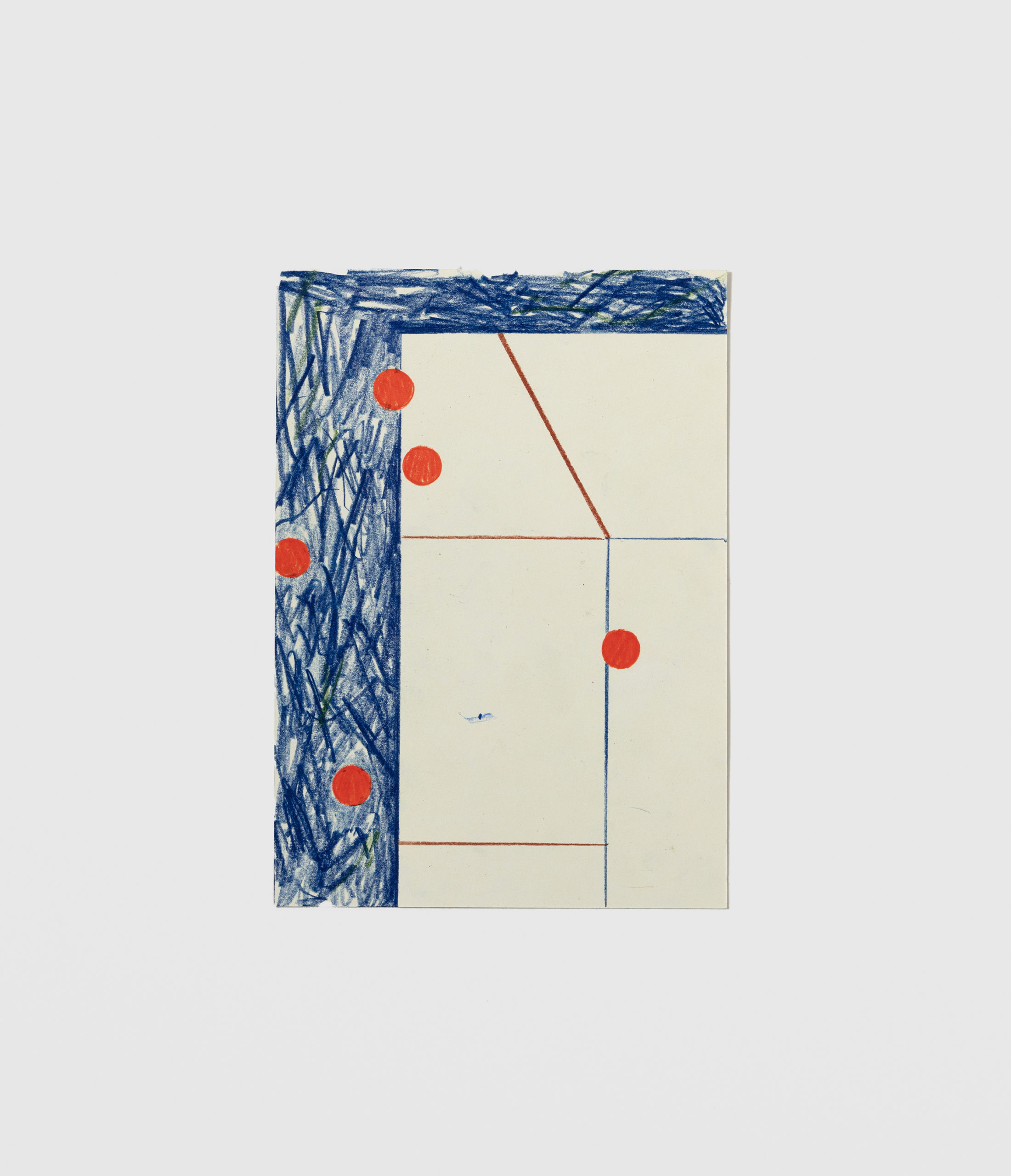

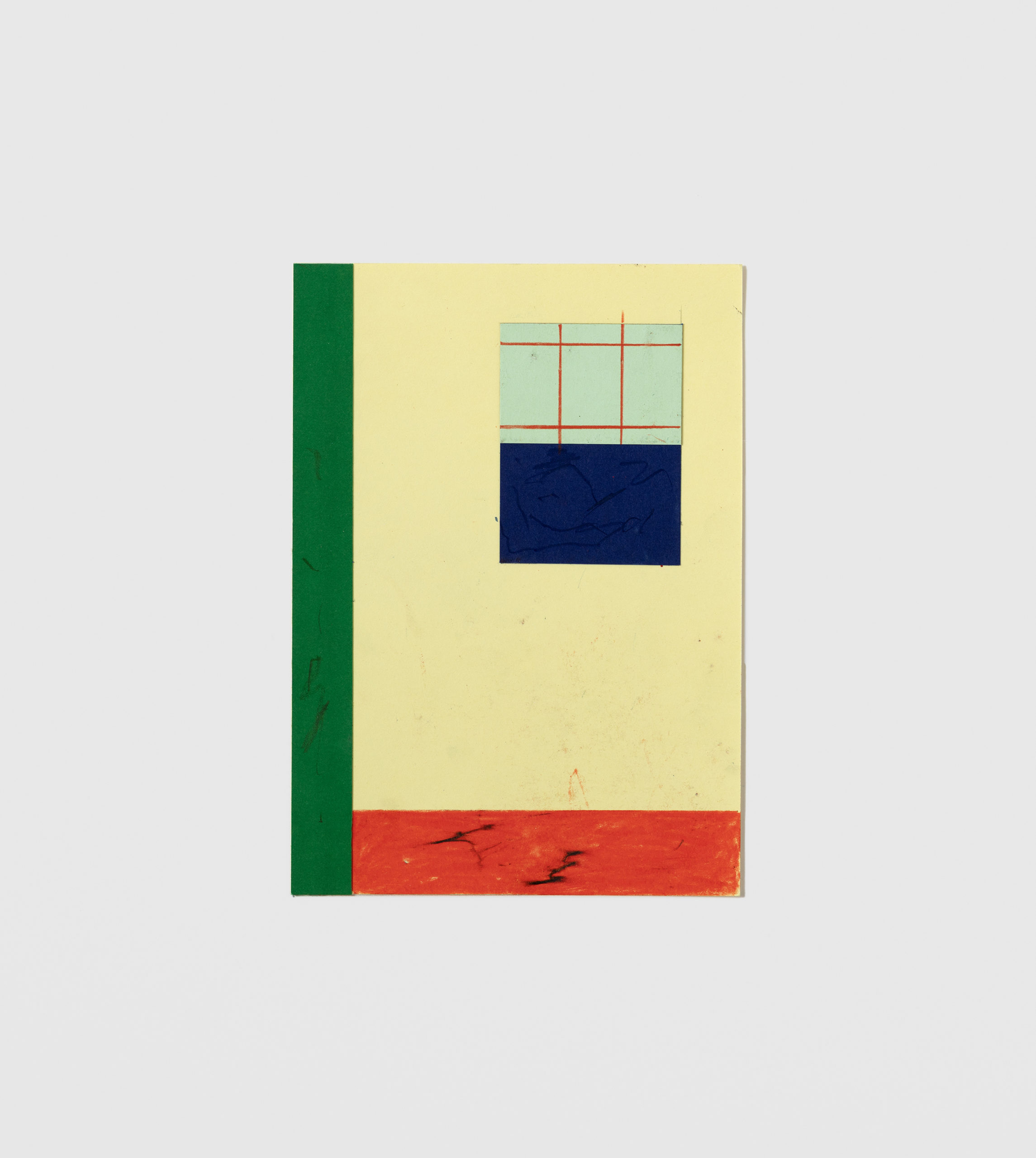

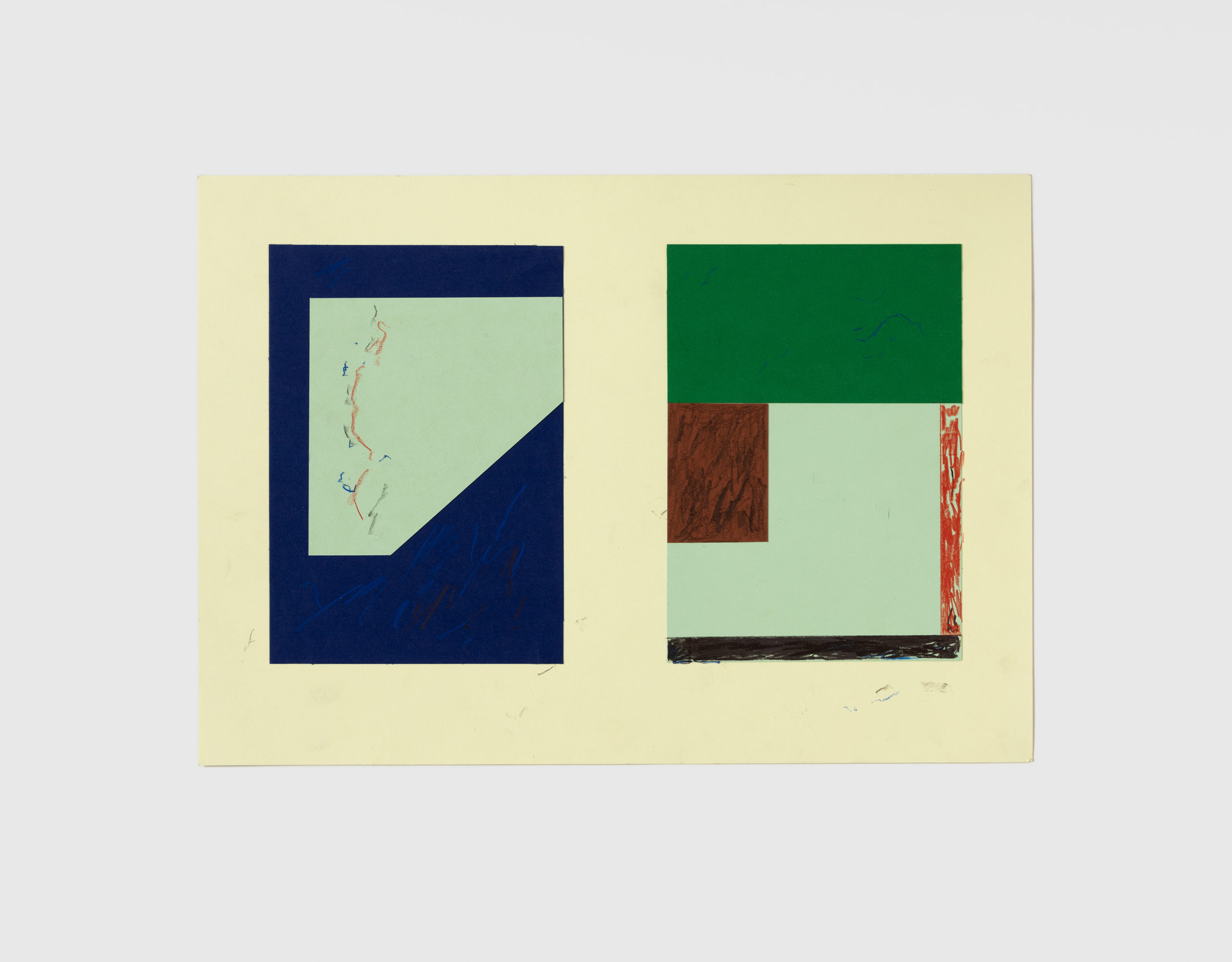

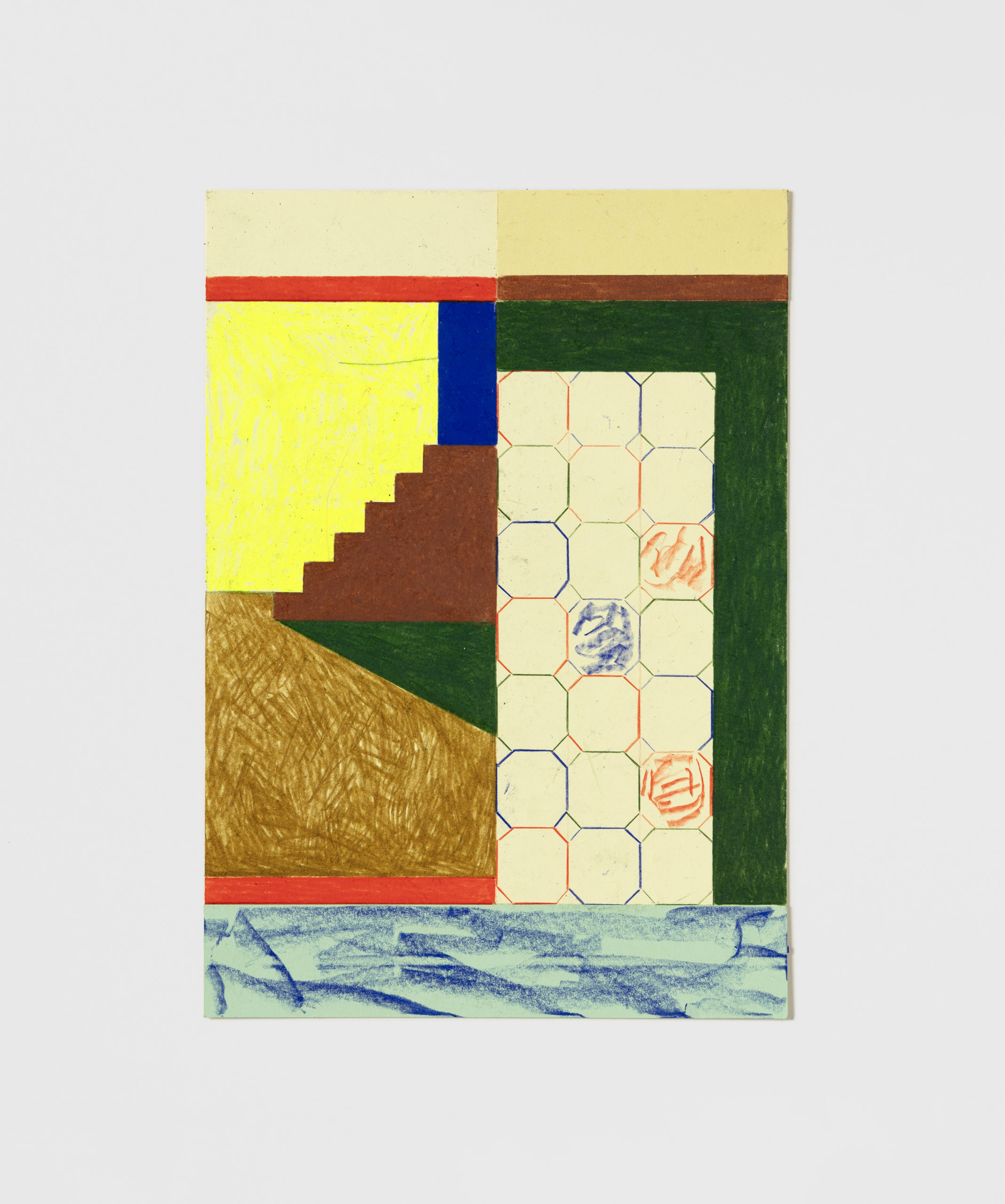

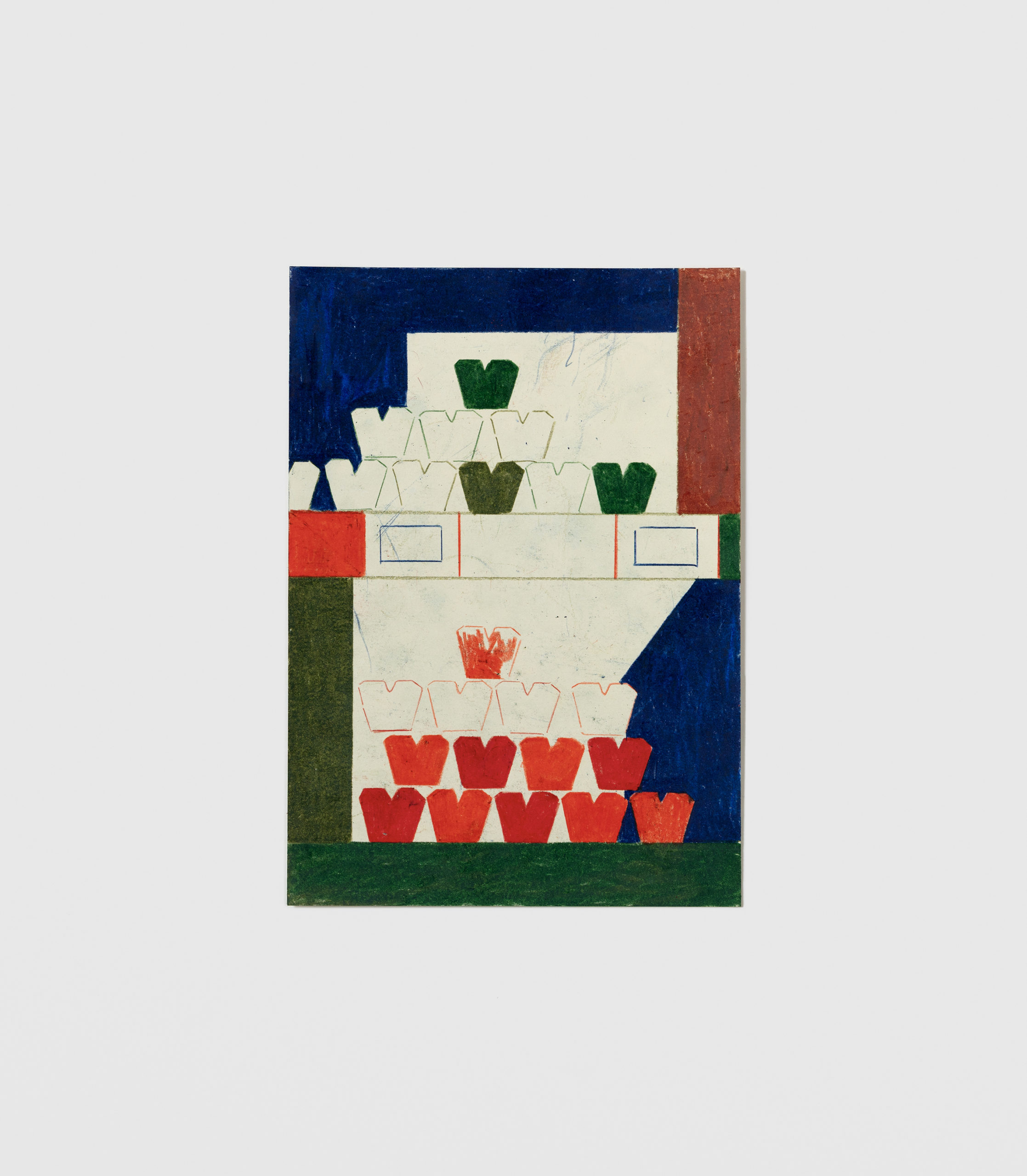

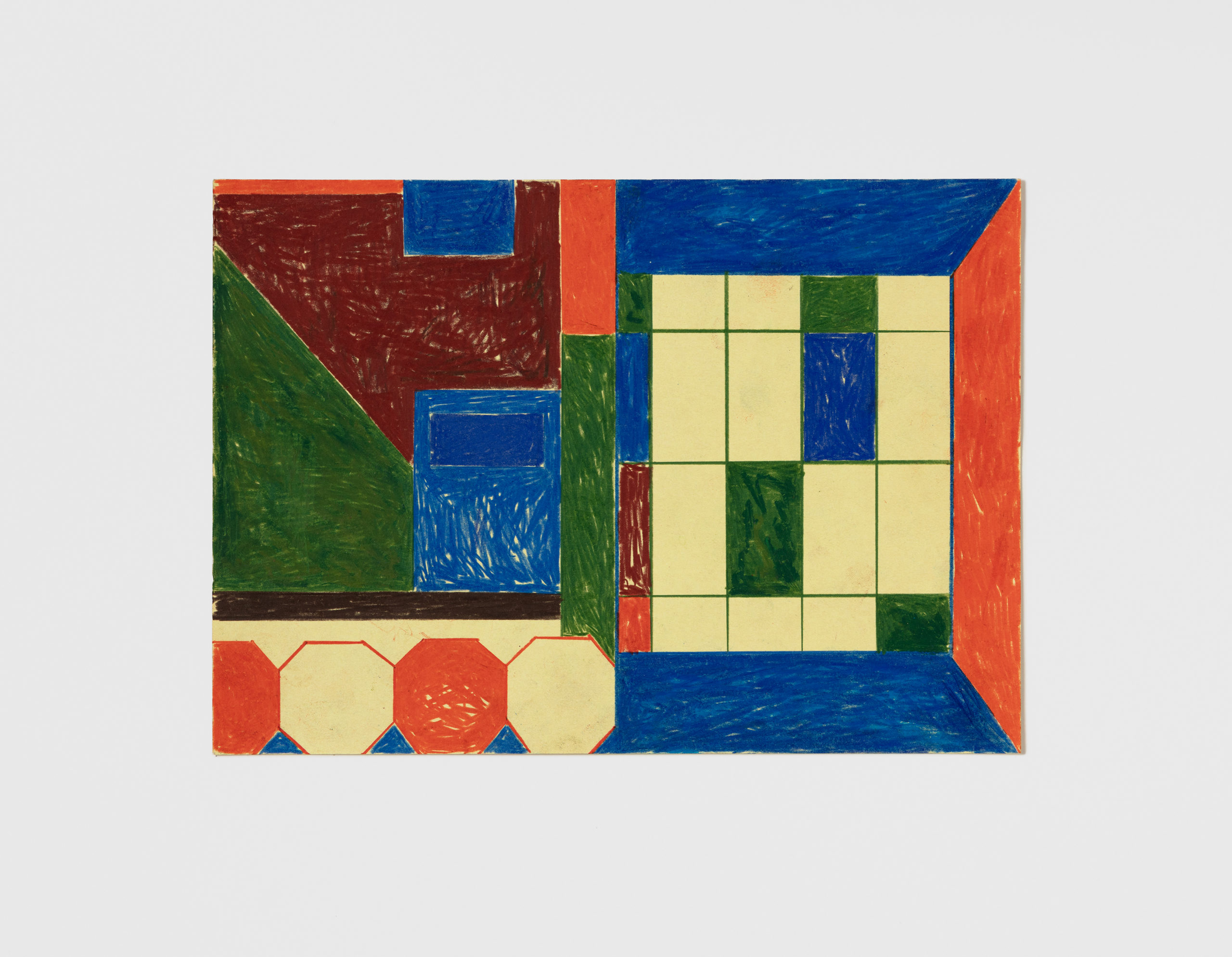

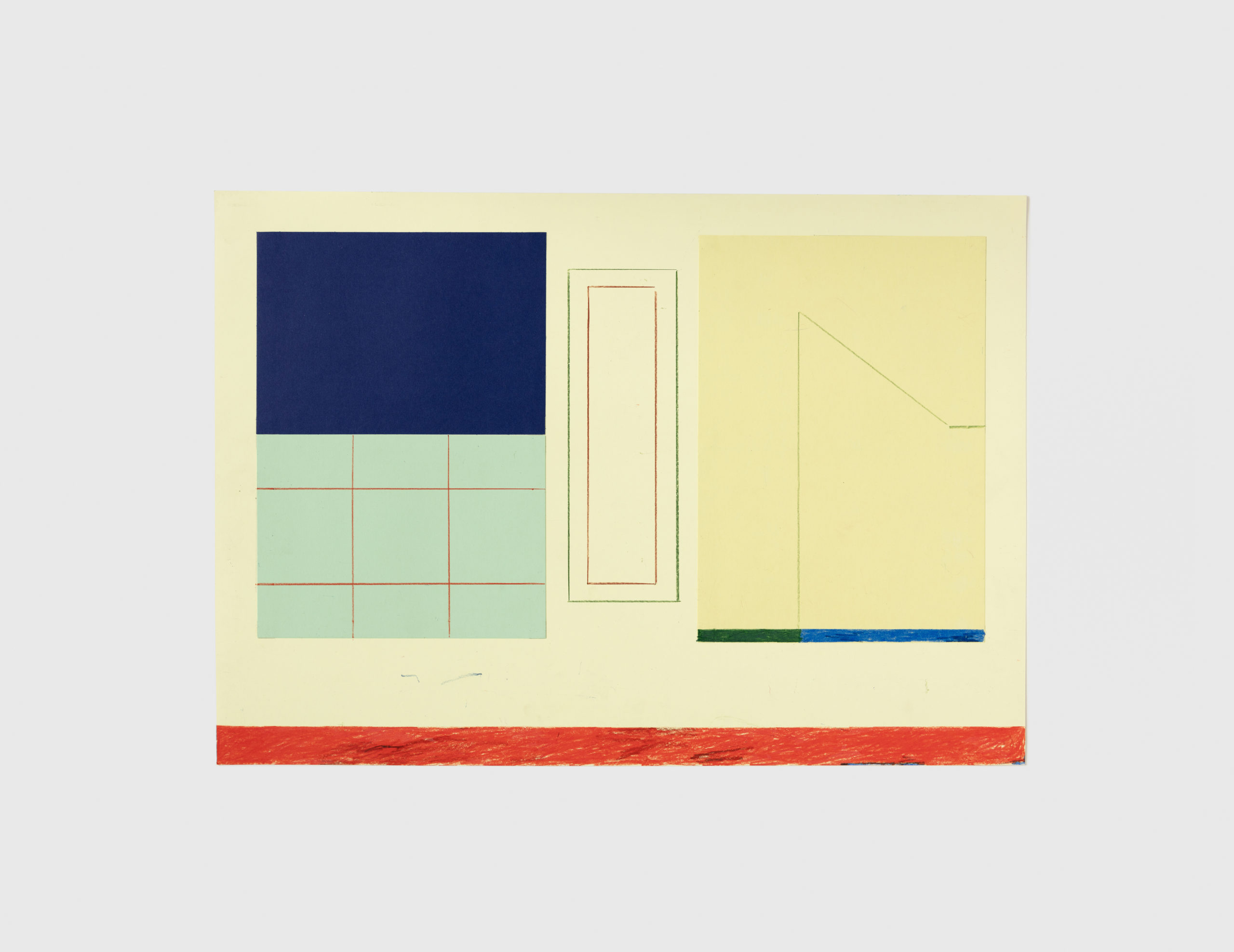

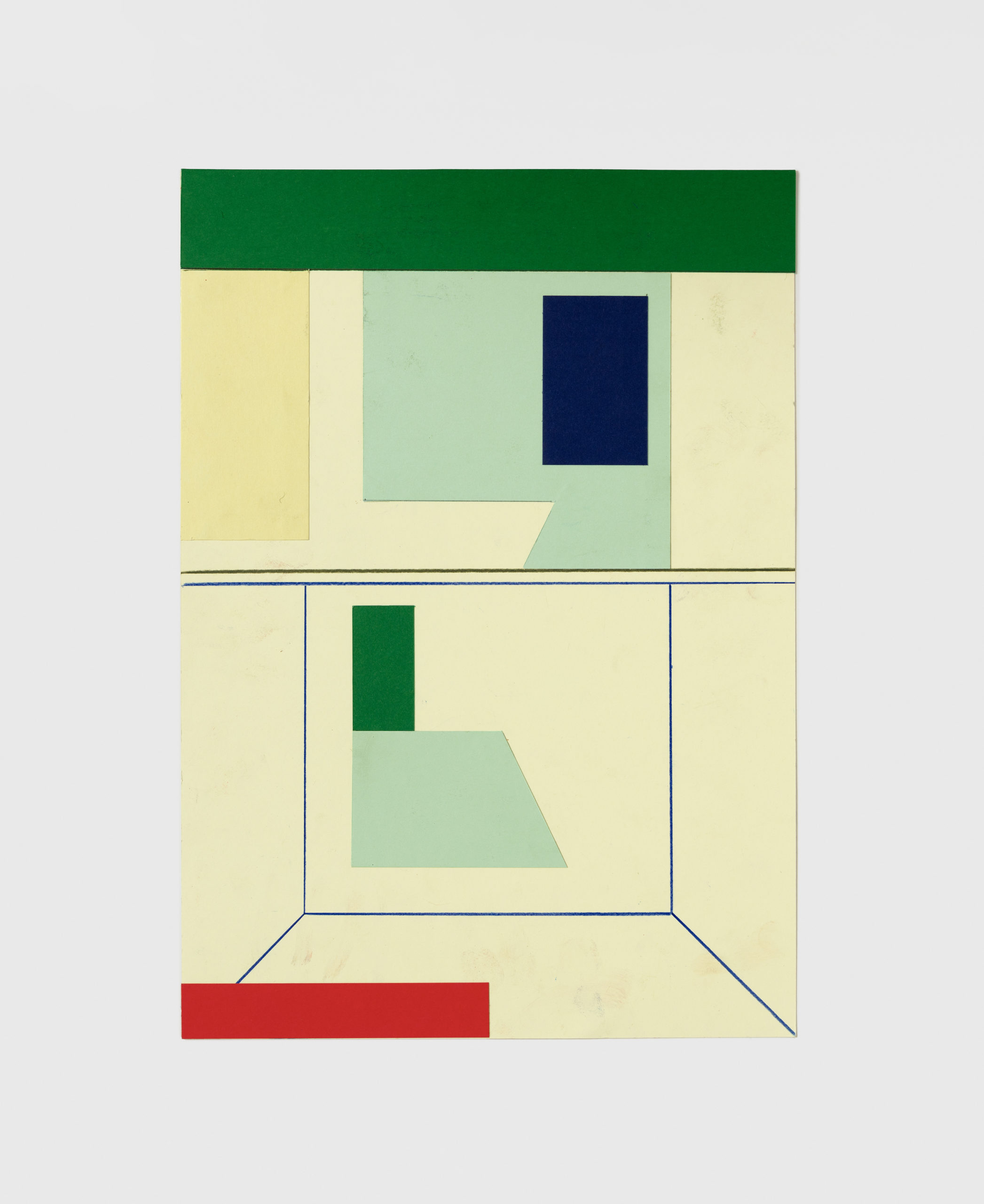

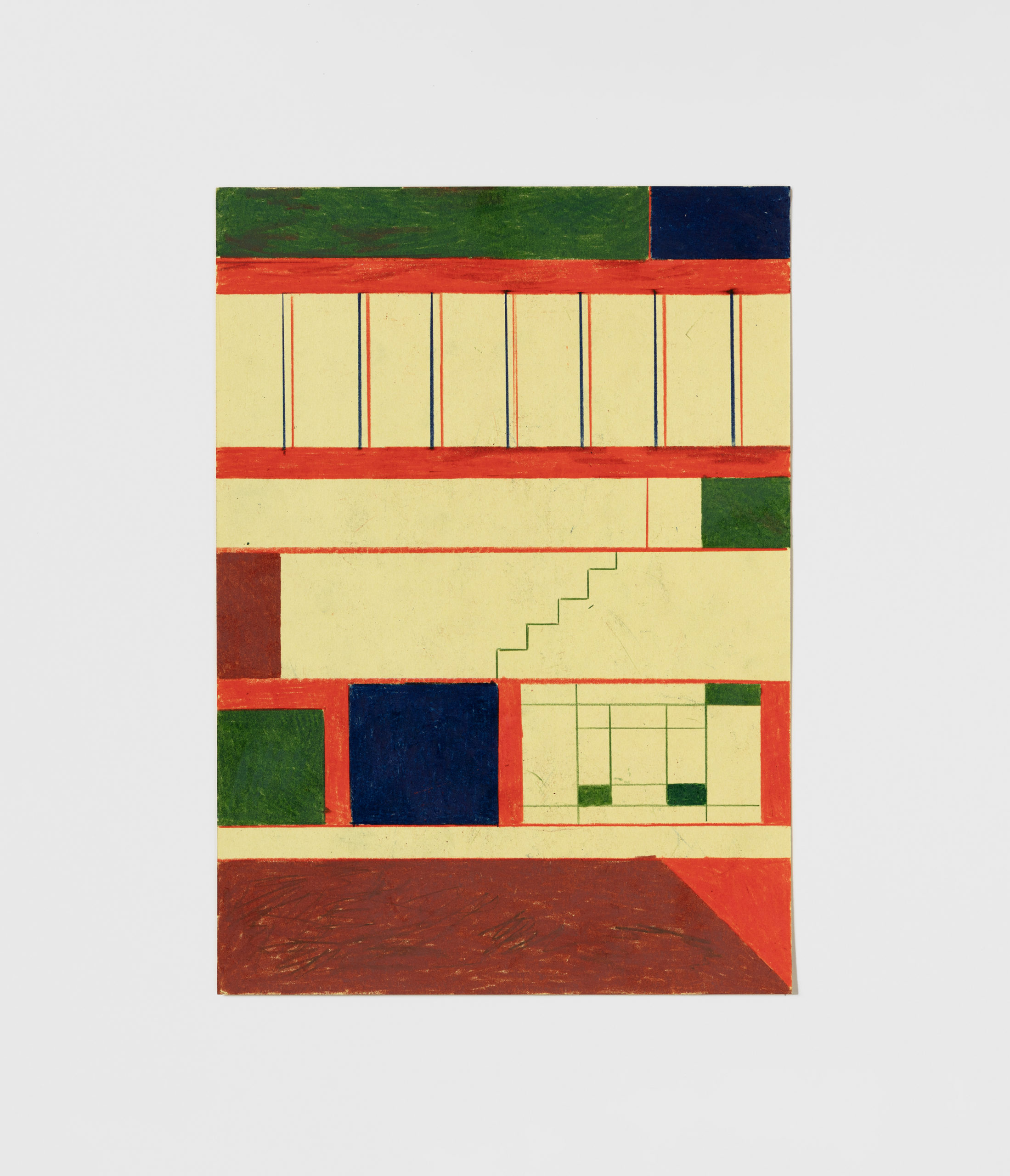

Mark works in part from photographic images and grows a personal library of architectural, figurative and other elements to play with. He uses paper cutouts to produce temporary collage-like tests for what might become a painting. (Like playing with paper dolls — ‘suppose you go here and they are there and this is the place you are in… suppose it’s just you in this other place, why hello!’).

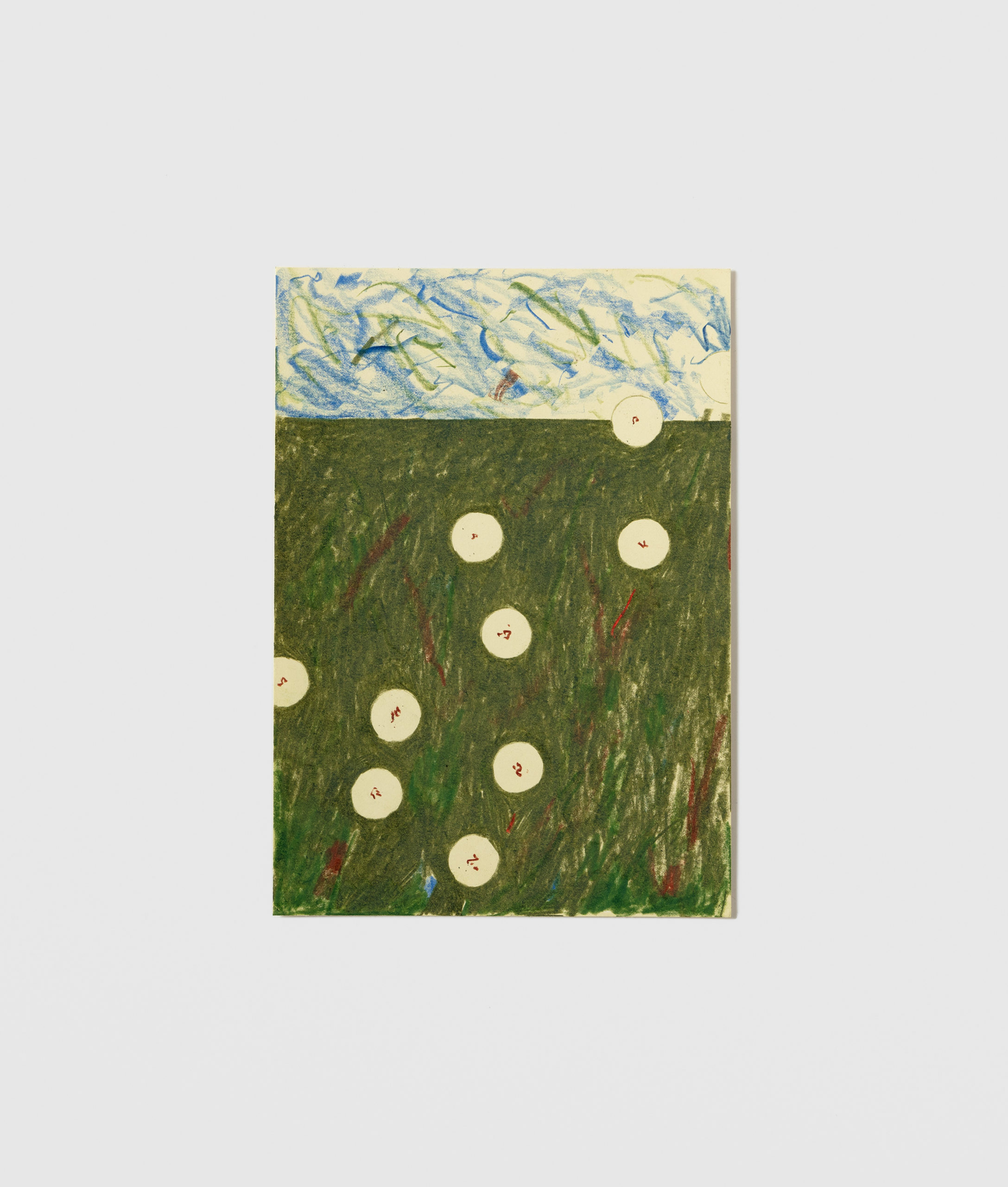

Subtlety is important to Mark. There are dandelions but he won’t rub them in your face. The flower is stripped back through his repurposing process. He takes sensory and visual information from the everyday that becomes part of a new landscape, corresponding to an archive of incidental formal qualities and elements to be played with.

His preference for subtlety is a mutually beneficial one, in that the artist’s own vulnerability is gently cloaked when he opts not to shout too loudly or explicitly (whilst still revealing himself just enough) so that access for his audience is left generously open.

We have joked about ways I might find to embarrass you, anecdotes I might include in this text (but promise I won’t!) — I seem to believe nothing’s worth doing where I don’t risk being a little bit embarrassed. In the words of Yassi Salek, I am cringe but I am free.

Nonetheless, we still all need to protect ourselves just enough that we can bring ourselves to produce anything (objects, actions, sentences) and share them, but not so well that we cease to be vulnerable because this makes our acts of sharing generous and meaningful.

Control — it’s not so much an elephant in the room as a rock in the ocean. But it’s also not so much a rock in the ocean as the line the water makes around that rock. (It’s out of our control?)

Each material utilised in these representations represents different degrees or methods of control and something about being able to shift between them is like relinquishing control and taking it up again, shifting lanes to diversify between different conditions or systems of control that ironically feels like a kind of play itself – the two ends of the horseshoe meeting.

Concerns about reception/perception, what meaning might be taken away, is another issue of control and one we have to let go — then, it cannot be taken away after all. People can, will and should produce their own meanings.

Vulnerability is hard but is sort of a given. Somehow, some of us (or actually all of us but I can never feel sure,) always manage to reveal ourselves. I’ve thought a lot about how to mirror your processes to find my own ways to redistribute, reduce, distil, to make a more direct line, managing material in such a way that protects and exposes at the same time. I admire that in your work. (This is a love letter! What could be more embarrassing than that?)

Mark introduced me to the work of Jackie Ferrara. Ferrara has described her preference for working with timber as coming down to the fact that she could control it. That evidently gave her pleasure and purpose. She also described her work as a form of chaos management. (So automatic were her working methods to her that she barely registered her output as art, initially.)

I’ll go so far as to say Mark’s doing a bit of chaos management himself. His studio processes play with what he can control and where he can relinquish that control to play. Another way of holding two things at once — paralogical thinking as process of producing.

(The rock and the ocean exist together. The water line around the rock is sharp one moment and diffused the next.)

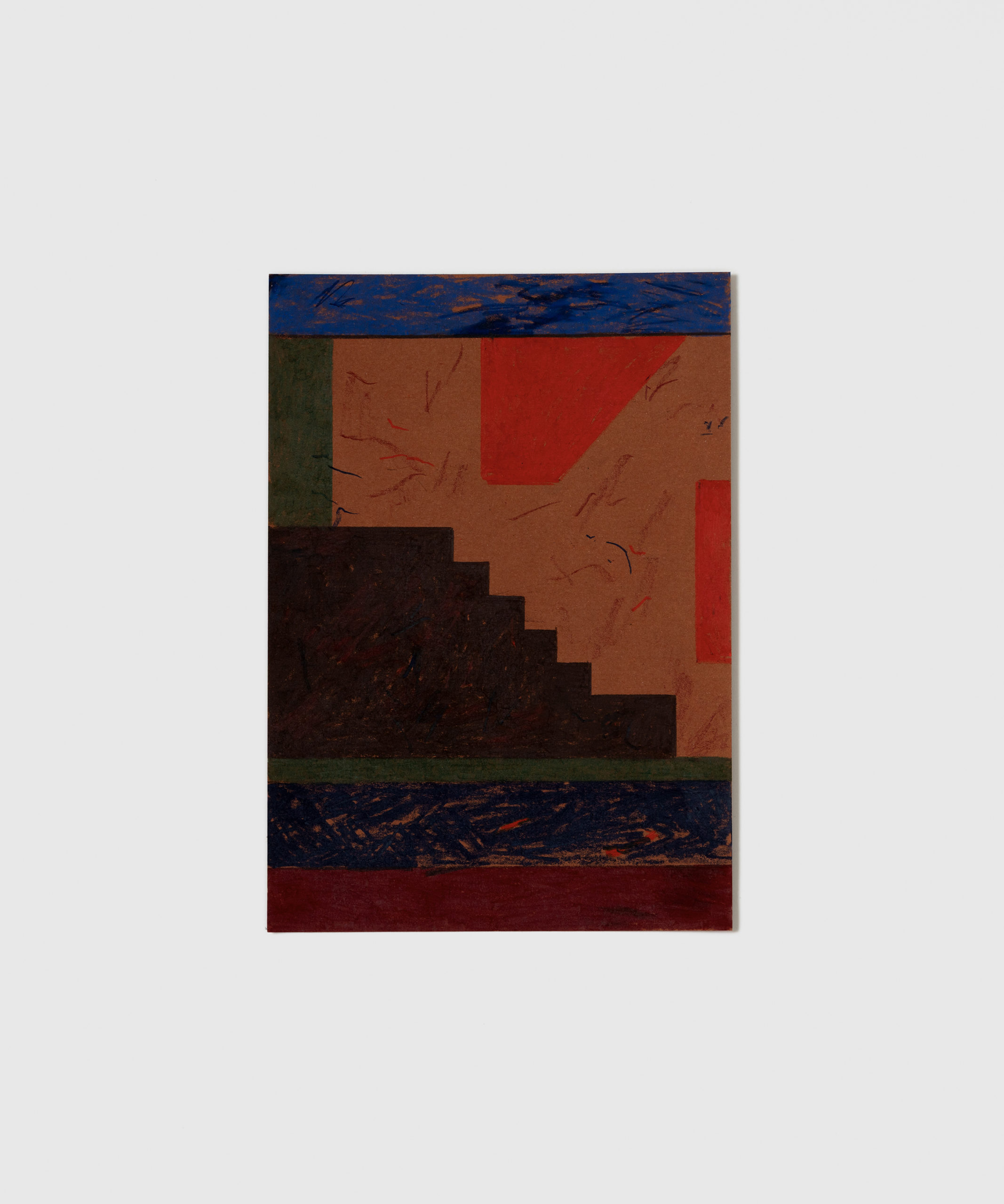

Ferrara questioned readings of her work as architectural. People can enter the work yet they aren’t about housing; the absence of plumbing undermines any architecturality. Place-making was an alternative idea that made more sense for her. More conceptually abstract than architecture perhaps — place, (like art) — goes to the core of our beings. What place means to people and what people mean in places might be relevant to wonder about in regard to Ferrara’s work, and Mark’s.

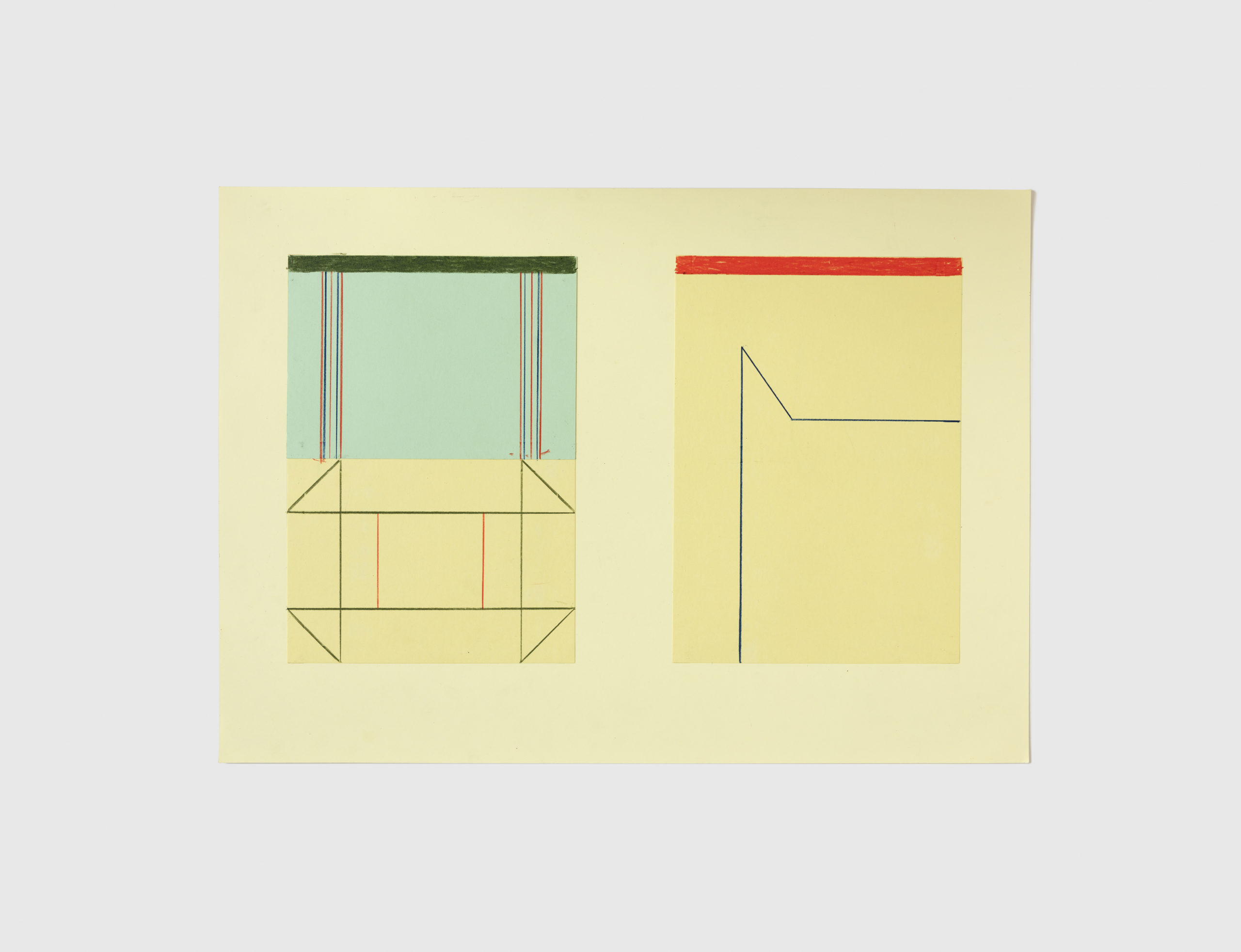

Mark makes use of architectural elements or references. Like Ferrara’s these place-ish environments don’t really belong to a specific time. (Any way we can find and stay in ambiguity between set values is important for how we function on earth, it can only be good for the world and human health.)

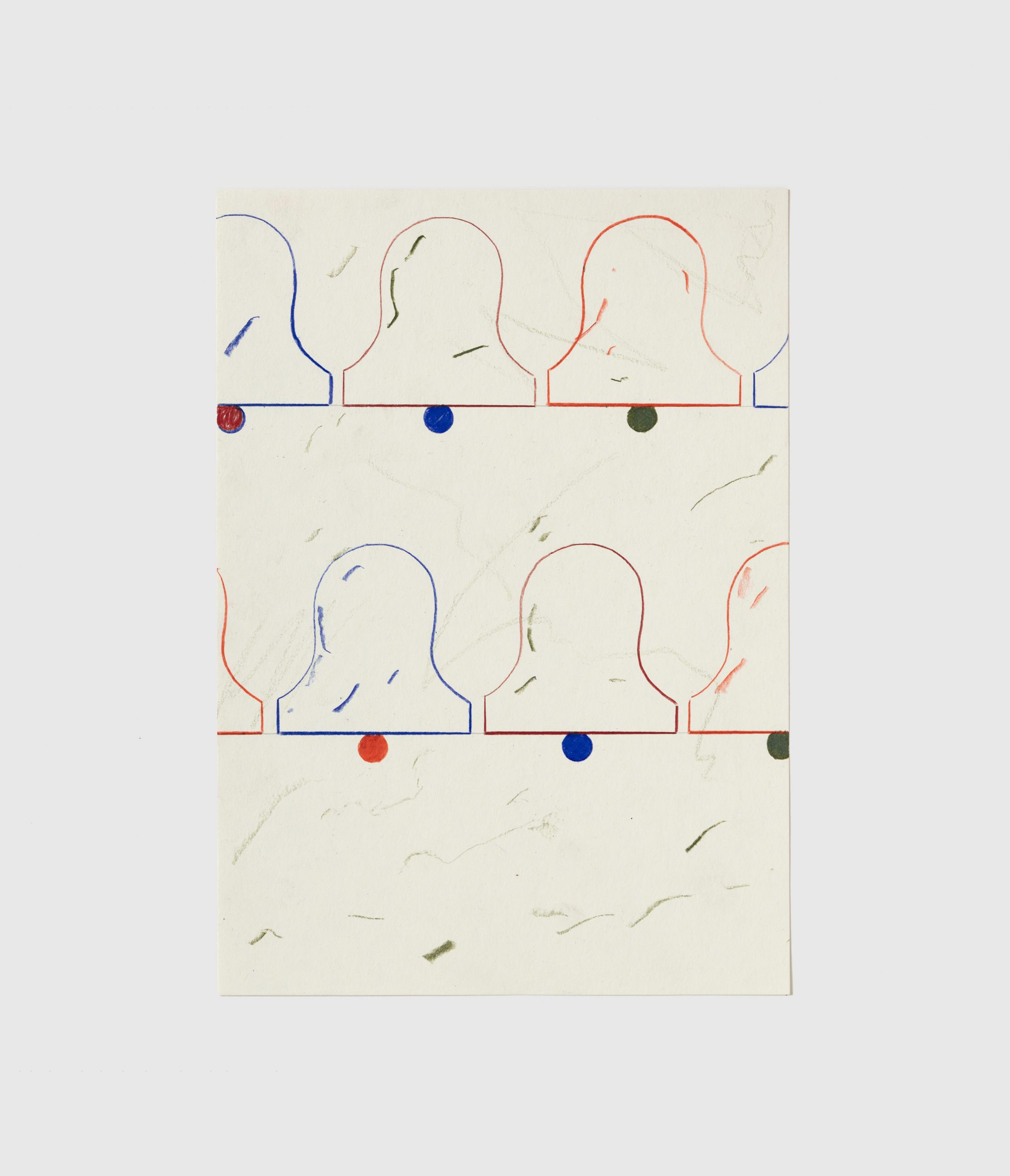

Some previous paintings have been peopled by figures with a similar non-specific peopleness. Not to say they’re universal, but they are general, and the sense of recognition in this non-specific peopled place is easily projected onto, and relatable.

Figures and places converge in a way that they become environmentally equivalent. For now, the people have left the building. They stand among us. Their places have unfolded, they might represent a view from above as much as an interior or exterior perspective on space, or both at once. They refer to the map and the territory without representing either.

I think of Mark walking to the studio and everything he picks up on his way. His output seems so inextricable from the everyday material around him. All the stuff that he uses literally and visually, but which I suspect also represents a spiritual dimension of his real life, doing things and making other things.

In my mind, the line he walks is a literal one, an enjoyable function of his human body, a means of transport to a studio where he makes paintings and drawings and sculptures but that is also useful to his practice as an artist in a spiritual and metaphorical sense.

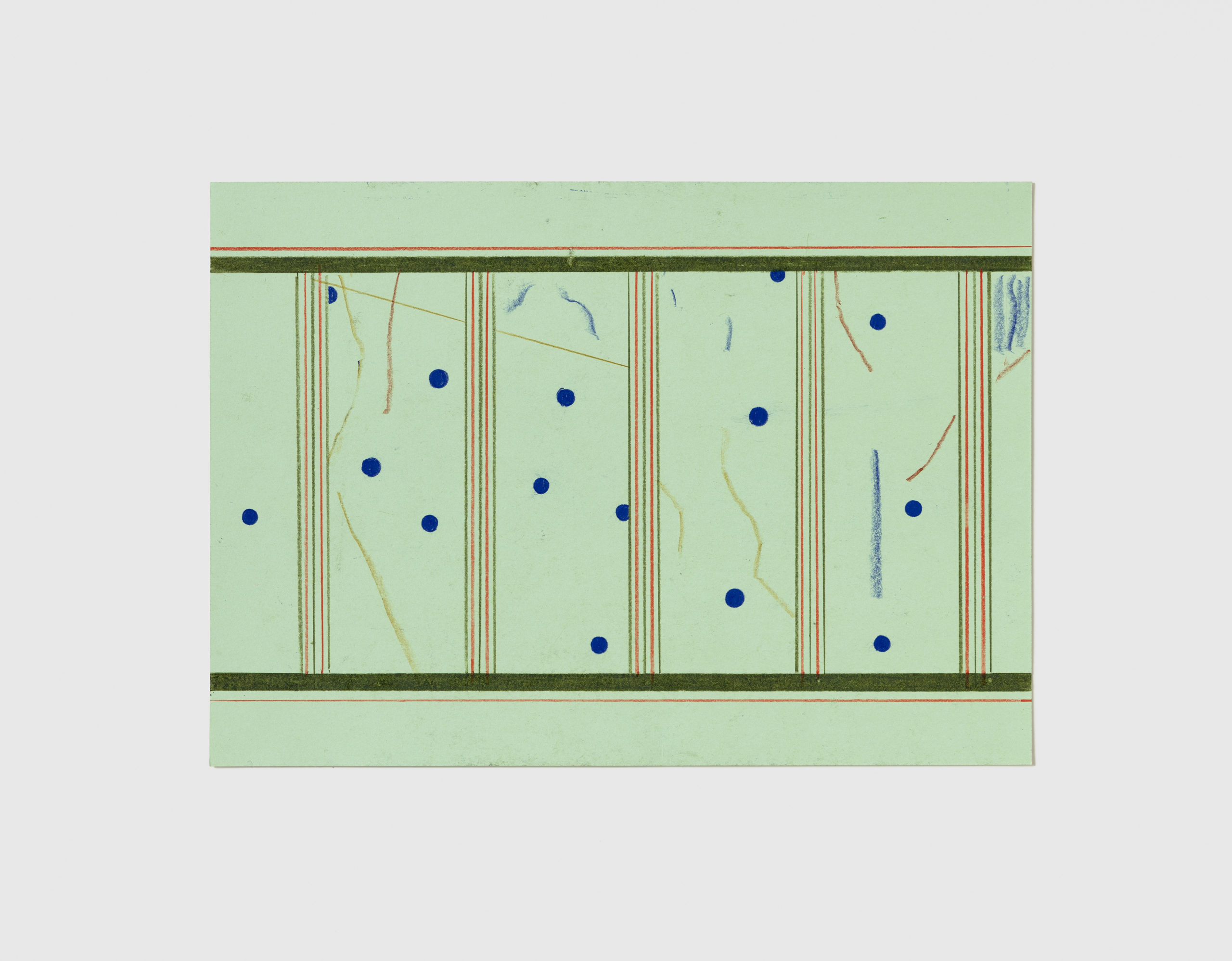

Lines lines lines! Everywhere, lines, and not just the ones we can see, immaculately drawn between discrete fields of complimentary and contrasting colour.

How you choose to register the line doesn’t really matter but it also means everything. (To me, the line is majorly out of focus, it’s quite wide and it is wriggling around. I like to zoom way, way, way in from an uncomfortable distance with a 10-megapixel camera circa 2011.)

I cannot escape my own sense of all art-making as a deeply existential activity. A method and a metaphor for endless existential life management and general reckoning. It’s been suggested to me that all representational painting is attempting to come to terms. For me it’s true, there’s always a negotiation going on. Just constantly.

This frames my view of Mark’s repurposing of everyday life in a way that literally gives him something to do: gathering things, references, images, mixing them up, filtering, redistributing. And over time increasing faith in the way something stripped back can communicate.

Little ‘f’ faith — though less visible perhaps than its capital ‘F’ other — is a very significant aspect of secular lives, allowing us to get up day after day and do anything. It’s an aspect of sanity, and so is doubt. Feeling doubt, and acting in faith, together demarcate the broad yet tenuous path between chaos and control that more or less expresses sanity as far as we collectively agree upon it. It’s a path that each of us has to find a specific way to walk. I think of Mark’s output as the result of navigating materials; a repurposing of the environments he engages. Recalibration in the form of painting, drawing and sculpture as a specific approach to making sense of this path.

I think the process by which Mark’s work comes about and some of what is visually conveyed speaks to an embodied presence that simply walking can open us to. I think painting presents another opportunity for it, though in my experience it’s not a given.

In a way, these paintings, sculptures and drawings are representations of a way of thinking available in embodied presence. The way they are successful is indebted to Mark’s capacity to access that when he walks and when he works, a suspension of other states that remain equally possible at the same time.

The way Mark utilises visual motifs of city streets and wild gardens is once more about striking balance. And also about shifting focus — a change in the environment you’re reading and ordering and repurposing. It cleans the lens inside your eyeball to improve the way you look at each.

It’s about balance as a principle for living and working that is reflected back visually in the work.

Mark draws from these visual elements that work in balance and can be played with and arranged formally or compositionally to reiterate visually what he already means through the process of making these works.

There’s an anti-Romanticism (capital R) to his relationship with the everyday, but his connection to the elusive nature of pleasure derived incidentally from ordinary things, the symbolic repetition of encounters with them, does something in the work that I find highly (little r) romantic at the same time. There’s no happily ever after, but the possibility of this might be contained within another ordinary but near-perfect moment.

It is like he very deliberately sidesteps any nostalgia, (he’s walking after all, he can step over what he likes.) And yet he resists any excessive future longing too. When I really ‘be’ with the work, I sense the pitfalls of my own mental habit of swinging in both directions. I feel so undisciplined and emotionally chaotic — yet also (significantly) I don’t feel judged!

Mark, if I look at your paintings and imagine an idealised version of me in a place where I am truly present, it feels futuristic because I can’t do this yet, today. It gives me a healthy aspirational feeling, like one day I will let go of what I need to let go of but not so much that I fully transcend and don’t still get to enjoy all the lovely human drama of life, but I’m in this imaginary place and I’m holding space for it all in a way that feels really comfortable and it’s not demanding anything of anyone else. I’m self-sufficient but I’m loved or at least accepted and the future is still not certain, but I’m so cool with that, and I really enjoyed my coffee that morning, even lining up for it and later in the afternoon it hasn’t made me anxious at all.

Is this just me looking for communion? Is my reading overlapping for even just a millimetre with your meaning? Am I writing when I read? I don’t want to overwrite but feel invited. If I’ve overstepped the line it can always be redrawn over and over again.

Marks’ work means that the artist, the audience, and the work itself participate in maintaining a tensional pathway through ordinary material and make from it something that transcends without either escalating, trivialising or resolving into a finite conclusion or interpretation. Live with it.

—Maggie Brink, 2023

Maggie Brink is an artist and writer currently living on the traditional land of the Kaurna people.

Mark Alsweiler (b. 1983, Aotearoa New Zealand) is an artist based in Naarm / Melbourne who works across painting, drawing and sculpture.

His work involves the collecting and repurposing of the every day, often abstracting material sourced from an immediate built environment.

Fruit Fields is his first solo exhibition with ReadingRoom.