I don’t know where I stand—

If you’ve ever watched a nature documentary, you’ve likely seen a number of different animals being born. It’s undoubtedly one of the most confoundingly charming events to witness. For many animals, from tiny rodents to horses, babies seem more capable and mobile than human infants. Newborn horses often stand up on their own within an hour of birth, whereas humans don’t take their first step until we are at least one year old and, therefore, spend our first formative months essentially catatonic. Apparently, it’s due to our ginormous brains, blah blah blah, but wouldn’t the fact that we’re born without ossified kneecaps also have something to do with it? Human babies aren’t not born without bone patellae; they’re just more of a cartilage-to-be-bone promise. Like sponge-compressors. It reminds me of when someone once retold a funny observation to me made by a famous funny person on how when you’re little, you simply can’t support your body weight in boring situations. Like how being 6 years old in line at the bank with a parent renders you in an amoeba-like state, where you spend the entire time graduating to the floor until you’re eventually completely flat, face down, like a stingray, intimately acquainting yourself with the blue-greyness of a 1990’s short-haired carpet tile. All the while, you’re violently aware of all the upright people that surround you—a sea of sober legs, by some sort of sorcery pertaining to gravity, are unconscionably erect. How did they do it? It’s boring even thinking about it.

The famous funny person aptly concludes this observation with something that made me audibly hee-haw: “This is what I think adulthood is: Adulthood is the ability to be totally bored and remain standing.”

Sessility is the biological property of an organism describing its lack of a means of self-locomotion. Sessile organisms, for which natural mobility is absent, are normally immobile, like barnacles, for example. They don’t move as adults. The baby barnacle larvae settle on what they hope is a good spot and then metamorphose, binding themselves to a location for their entire life. Some baby barnacle larvae, however, have the savvy to implant on turtles and thus get to travel the world, but other baby barnacle larvae will find themselves years on, fully grown, having spent the entirety of their life-hood on the same rock, in the same ocean pool, next to the same barnacles. At first, this made me feel sorry for the latter baby barnacle larvae as it was fated to a life of lassitude, but then I decided there was something wildly empowering and oddly productive about being in one place forever, undecidedly/decidedly sedentary, resting…relaxing…existing. And that is that actually, so much can be achieved in physical inactivity and that inaction is a highly viable, legitimate form of productivity—an empowering choice not to respond to stimuli. Take the psychoanalyst’s couch, for example. The couch became a tool to help patients free-associate. The first psychoanalyst’s couch was a Victorian day-bed – reportedly given as a gift to Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud by a grateful female patient, Madame Benvenisti, in around 1890. Freud found that lying down, looking up at a ceiling, promotes a loss of control that encourages more instinctive and, ergo, productive conversation. Patients who decided to use the couch during their sessions, it is claimed, had a significantly positive impact on their therapy compared to others. Maybe it’s something about the opportunity for both patient and therapist to both bear and use silences for reflection in an effective way, to allow feelings and thoughts to emerge and be explored without concern for usual social discourse like eye contact and facial expressions. (I can relate to this, after a long day of being in the world, all I want to do is lay in a darkened room, peel my face back and let the white noise pour out of me: the purgation by ritual of morbid social emotions.)

However, for some, the couch may be quite frightening or daunting. A great degree of trust in the therapist is needed, and even then, the feelings evoked when lying down can be quite overwhelming. Like, what would it feel like for a female patient vulnerably laying down next to a male crustacean-aged therapist? I imagine Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres’ monster painting La Grande Odalisque where a female sex-slave/concubine is depicted lying down, nude, on a velvety couch with a history of men sitting behind her. She fits right in re: depictions of women in art etc., but there is one anomalous feature that, just like a human infant, renders her unable, if she were to try, to stand up: Ingres painted her with too many vertebrae. Bravo! The painting has elicited outrage from critics (past and present), who ridicule its radically attenuated modelling as well as Ingres’s habitual anatomical distortions of the female nude (he likes us lying down). Ingres’s odalisque is a creature totally unknown in nature. The outrageous elongation of her back, together with her wildly expanded buttocks and rubbery, boneless right arm, constitute a being that could exist only in the erotic imagination of the artist…in a perpetual state of reclination. All the while, her gaze screams, “get me out of this bank!” !

Zuo yuezi, literally ‘sitting the month’, is a traditional Chinese practice following childbirth. The custom, documented as far back as the year 960, is referred to as ‘confinement’ as women are advised to stay indoors; specifically, lying down in bed to recover from the trauma of birth. During zuo yuezi, mothers are told not to expose their body to physical agents such as cold weather, to have minimal contact with water (e.g., bathing/washing hair), not to read books or cry (because water?), have sex, or exert themselves in any way. Like a postpartum sick bay peppered with more gravitas: a private sanctum where women are afforded rest from the psychic and social exhaustion of having had, for the first and maybe last time, a kneecap’less human emerge from their nether’s. It kind of reminds me of a time I went to sick bay in high school after a casual lunchtime ritual ‘Light as a Feather, Stiff as a Board’. I was told I was too emotional to levitate (?!) by my accompanying fans of The Craft, and was, therefore, to put it simply, rendered a dud. I ran like Josie Grossie straight to sickbay with no referral from a teacher, pleaded with the nurse to “pleashe jusht let me lay down and be emotchional in private”. She agreed, and finally, I found myself marbled over a couch for periods 5 & 6. As I lay there, flooded with myself, the nurse came in to check on me. Without prompting, she began to speak lowly, softly, regeneratively. She said to me, “sometimes we need to go all over the place in order to resume a straight line”. Staring up at the ceiling, I remember feeling a welcomed loss of control, a visceral state of listlessness—ideas and thoughts productively binding themselves to eternal resting places. Like me, on that couch, feeling like a barnacle with too many vertebrae, just needing somewhere to lay for the rest of eternity… light as a feather, stiff as a board.

—Emma Finneran

Emma Finneran refers to herself as a painter, yet she also refers to herself as a designer, scavenger and half-baked sculptor. Her sources of inspiration include fashion, rubbish, female authors, Lismore, private inner-worlds, soul music, and so on. The unexceptional in everyday life is central to Finneran’s work – as a disaster or a glimmer of hope – for in her case, the things cast aside are what she reveres most.

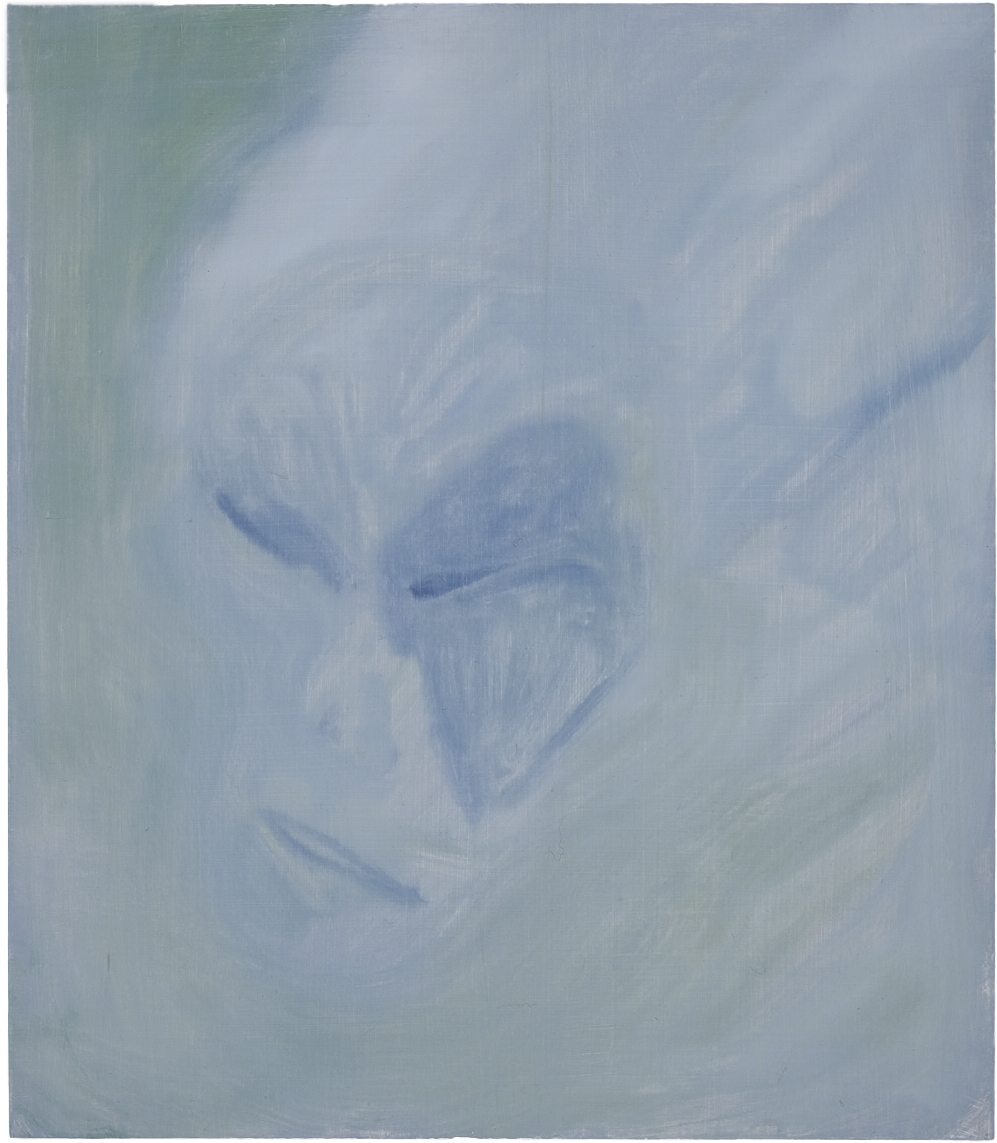

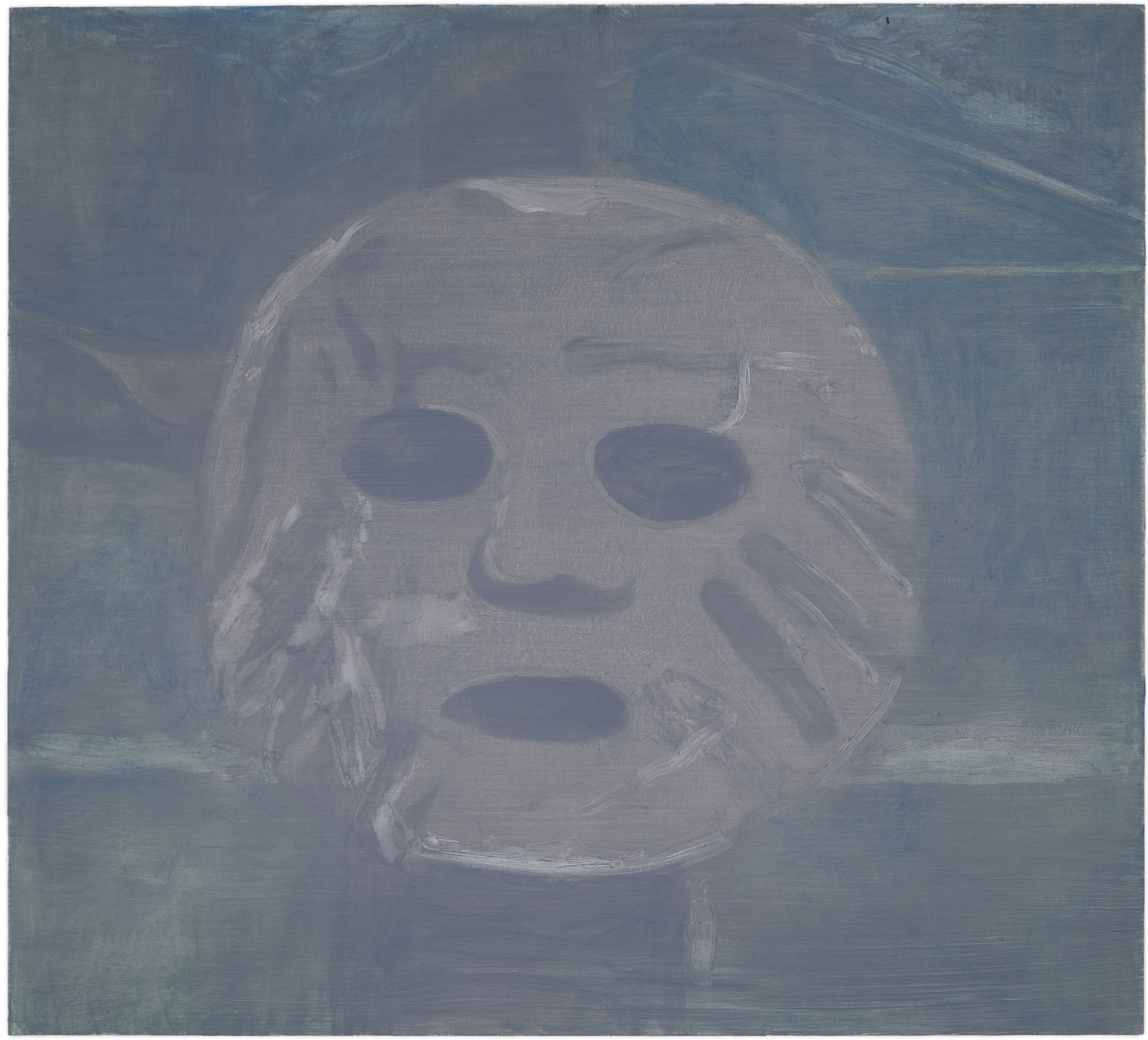

Maggie Brink’s paintings —layered and ghost-like representations of inanimate objects, landscapes and figures— are exhibited alongside sculptural works and textiles that are dyed, printed and sewn in different ways, sometimes with graphic imagery or text overlaid.

Transforming her references— tv shows, cinema and theatre, slogans, generic branding, (pseudo/) science, popular culture, history and mythology and a growing archive of her photographs and found images —through these constructed environments, Maggie creates and explores subtle and awkward exchanges — trading in subjective associative responses to produce open-ended and multiple meanings through her work.

An ongoing interest in Maggie’s practice is the way that exchange—with oneself, between oneself and other/s, with the world—and the reading and negotiation of images, texts, environments, other bodies — necessitates awareness and negotiation of boundaries: psychic, spiritual, physical, porous.

Maggie Brink (b. 1983, Brisbane, Australia) currently lives and works in Melbourne, Australia. She received her MFA(2020) from Sydney College of the Arts, where she also completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Honours) in 2014. She has participated in numerous group exhibitions in Australia and New Zealand, and recent solo exhibitions include Alien Alien Crocodile Shadow, ReadingRoom, Melbourne (2018), Pale Blue Dot Dot Dot, Firstdraft, Sydney (2017), County Athletics, Knulp, Sydney (2017).