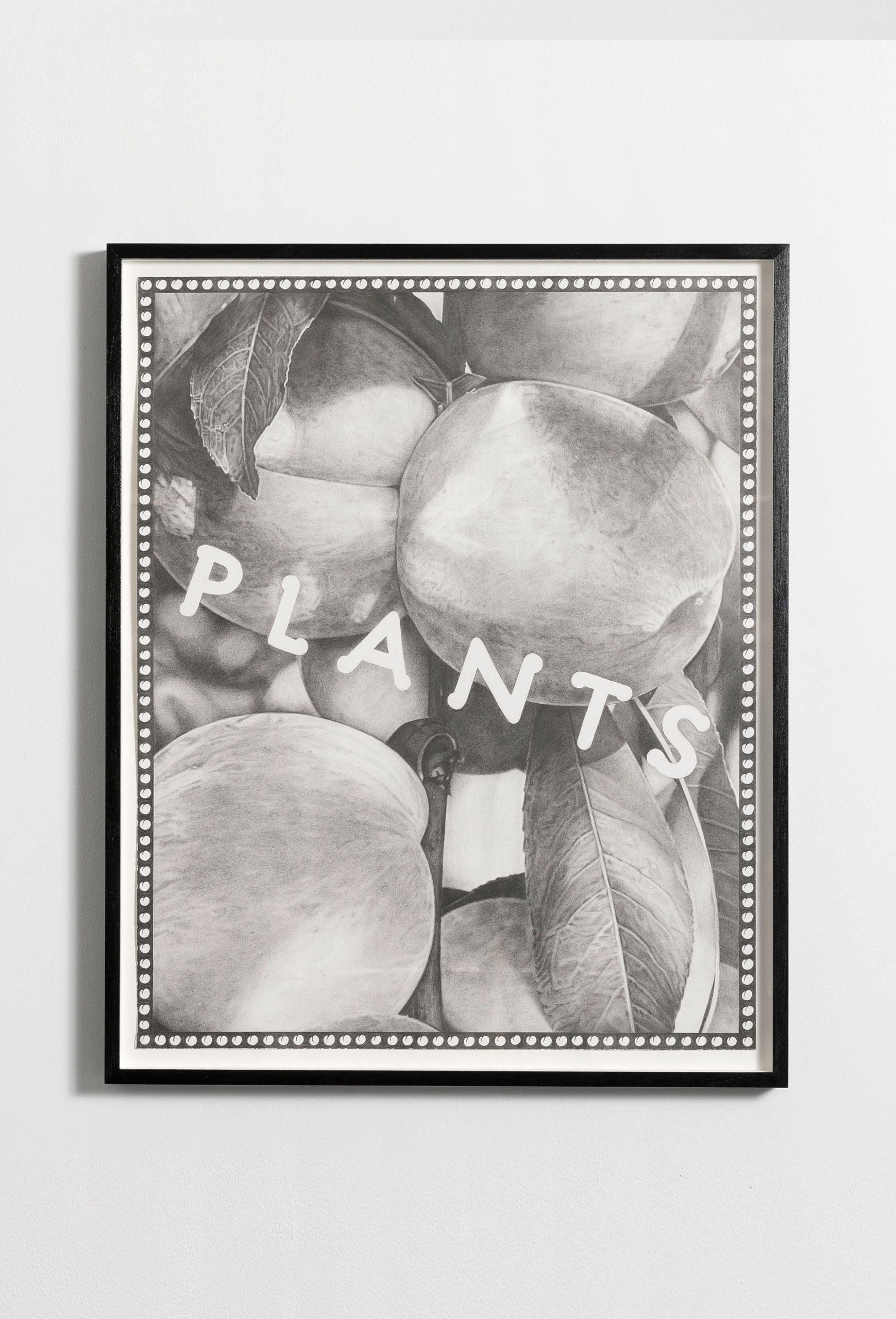

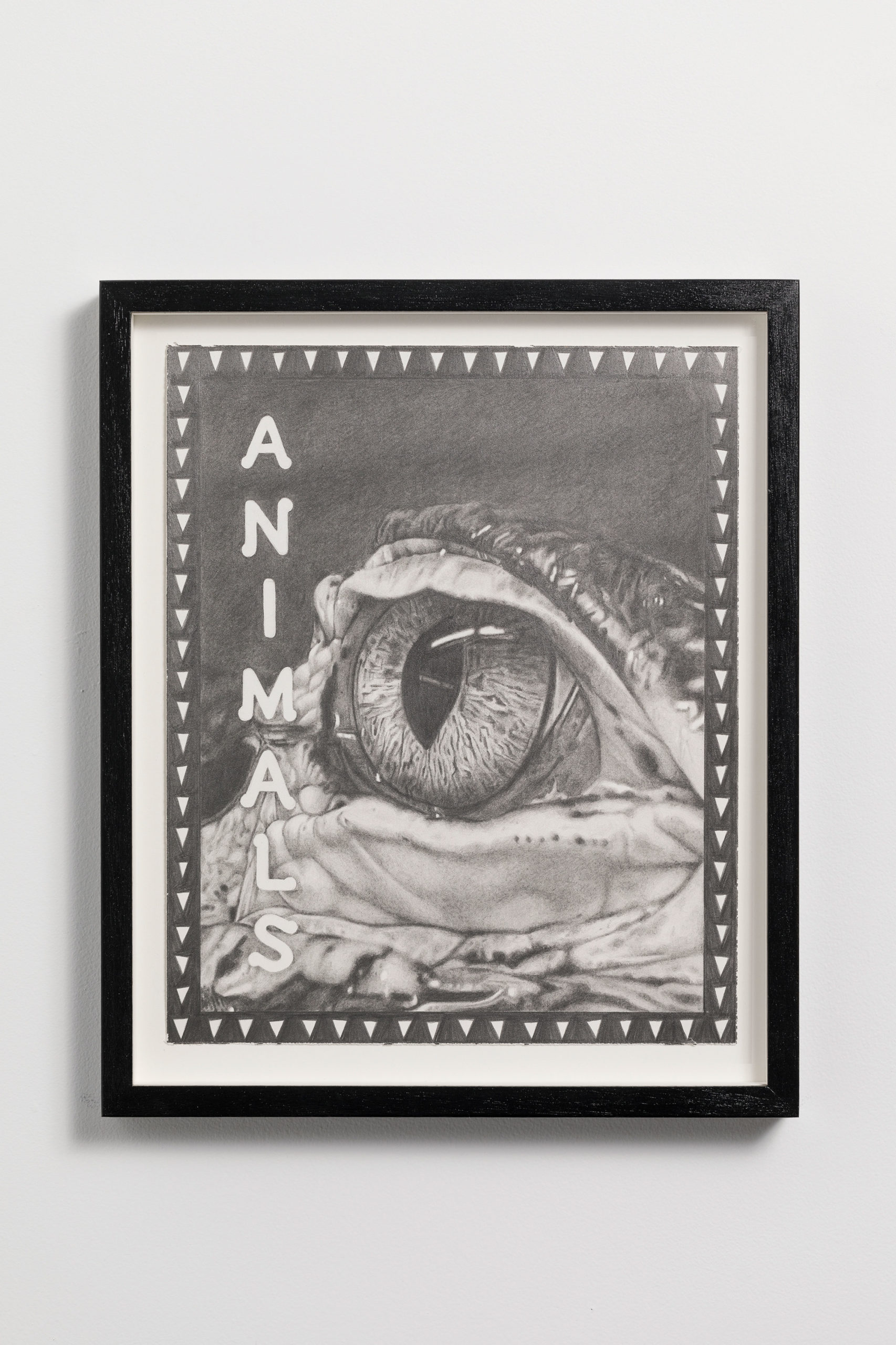

Plants + Animals. ANY DAY NOW.

Focusing on flora and fauna may seem too narrow a range for Riley Payne’s image and text puzzles. In the past, Payne has loaded his images with enigmatic but suggestive slogans, often a subversive response to the virtuosic scene behind them. He stamps the things we shouldn’t think on his meticulously-rendered graphite drawings.

So what, then, accounts for this change?

In this new series, the word “PLANTS” describes the plant, and the animals are likewise branded by their signifiers. Payne has even framed these drawings with squared tiles, often alternating in stark grey and white, little emblems of the flora and fauna represented.

Perhaps, in this current political climate, which itself is inextricable from environmental despoliation, it may be a good time to be skeptical of subversive snark, and instead think more fundamentally about our relationship to plants and animals. Like Payne’s decisive choice of carbon-based medium, we’re all connected, dude. But it’s not that simple.

Animal. Plant. Man. Eliminating all other words and snipped phrases forces us to concentrate on the sound and shape of these words, both in the mouth and on the page. The repetition of “-an” in plants and animals calls to mind our assumed place. Man, woman, human. Payne’s inclusion of text is another reminder that as humans, what we see is already irrevocably changed: our presence, and our inability to accept what we see without naming it, transmutes our gaze.

Human instinct is to classify and relate. According to John Berger, by way of Claude Levi-Strauss, if language developed out of speaking in symbols derived from sharing close quarters with animals, “the essential relationship between man and animal was metaphoric.” We look to nature to find ourselves. Animals are the original Other: how we treat them is an inverse reflection of how we treat ourselves.

In the history of art, plants and animals were survival, so naturally they constituted the first medium and subject in cave painting: pigments from plants, animals on the walls. More recently, still life and paintings of livestock have been the province of the very wealthy, while working directly with plants and animals has been the lot of the peasant.

Look past the flattening text of the words in Payne’s work, and register the blur of the photographer’s lens, and the smudge of the printers ink. These are not life studies, but scrupulous renderings of the several screens (camera/computer/phone) that separate us from nature. This distance only amplifies our desire to find resemblance and connection.

Observe how this plays out in Payne’s work: although he uses the same font on each piece, the rather silly rounded serifs start to resemble the subject. The club feet of the letters echo the digits of the frog, the ginkgo’s seeds, and, when arranged in a curve, emphasize the centrifugal growth of the cabbage. And that thing that we humans do, searching for resemblances, happens in spite of our cynicism: the space between the words and the images is narrow, but dynamic. Each piece offers us the opportunity to find our place within it.

Reductive words applied to blurred, recycled images constitute something of our experience today. These are search engine terms that reveal our subjectivity. How we search, and what we see when we look, is our humanity.

—Theodore Barrow

Theodore Barrow is an art historian, writer, and lecturer living in New York City. Specializing in the Gilded Age, both then and now, he is currently working as the Assistant Curator at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers.

Riley Payne (b. 1979, Melbourne, Australia) has held six solo exhibitions since 2008; his most recent include Any Day Now at New Release Gallery, New York (2018), Serenader at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne (2016), and his work was included in the inaugural NGV Triennial (2017–2018). He was a finalist in the RBS Emerging Artist Award (2011), and has held a residency at Artspace, Sydney (2014). Riley lives and works in New York, USA.