Tryst

Here it’s quiet, here it feels good,

here the meadows are fresh and pure,

and a spot in shade and sunshine

like well-behaved children.

Here the strong desire

that is my life dissolved,

I no longer know desire,

here my will dissolves.

I’m so still, so warmly moved,

lines draw through my emotions,

I don’t know, it’s all confused,

yet everything’s been proven wrong.

I no longer hear any complaints,

yet there’s complaining in the room

of such a soft kind, so white, so dreamy,

and again I’m left knowing nothing.

I only know that it’s quiet here,

stripped of all needs and doings, here I can rest,

for no time measures my time.

From Poems (1909)

— Robert Walser, translated by Daniele Pantano

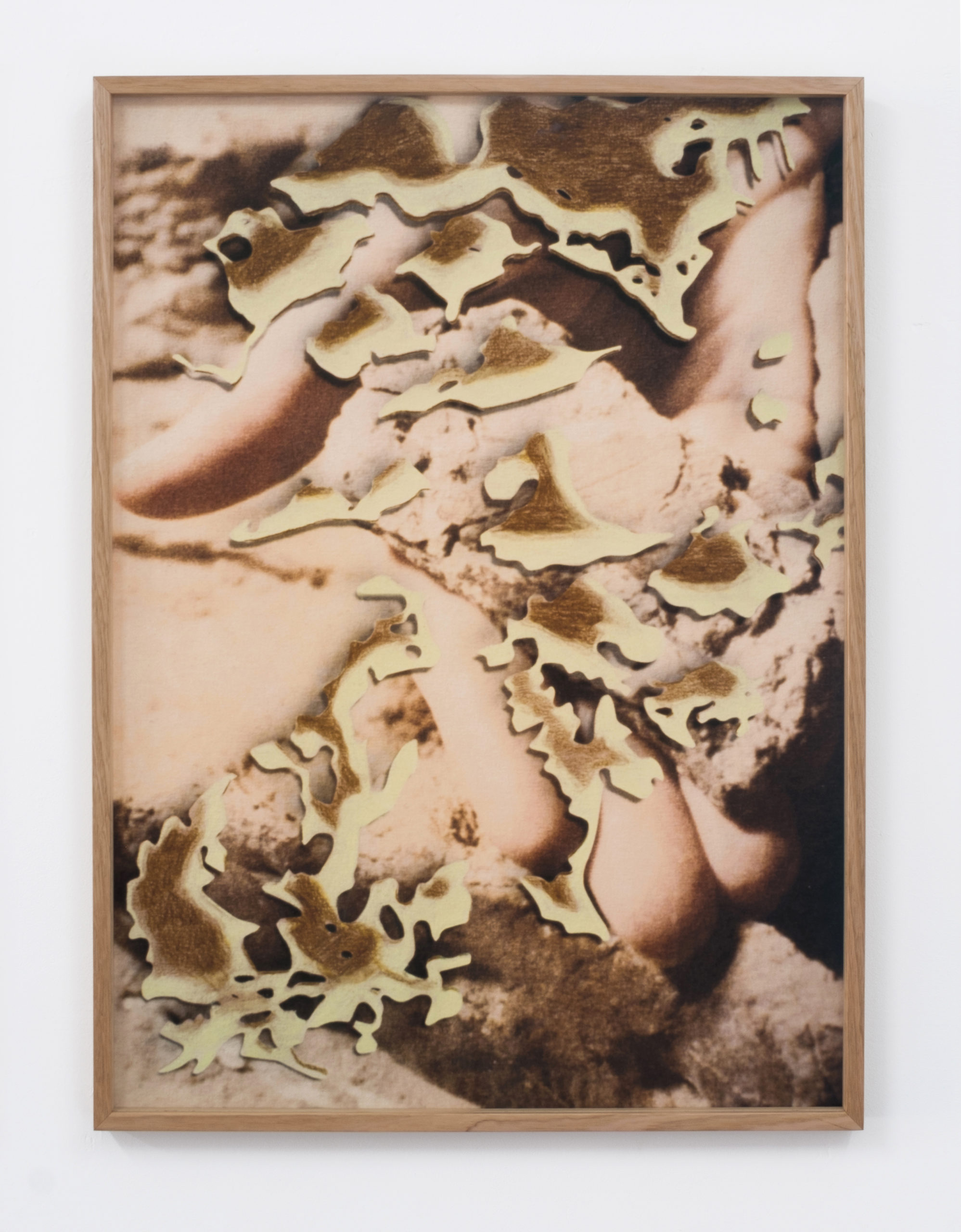

Look now – Anna Higgins’ Omens

Anna Higgins layers and condenses found and made imagery within a porous frame. She uses what she makes along with the materials that she finds, responding to and acting within moments and events in the world. In this sense her work is firmly anchored within the real with all its nuances. But what is real given our ever shifting physical, emotional and intellectual relationship to things?

The impulse is to clarify, to capture what is seen and felt. What is actually experienced sensorially, generally speaking, is a blur of different kinds of movement. The mind is never still even when asleep, and the world is always turning. These truisms are broadly indefinable, so how to give intelligible form, within the frame of an artwork, to aspects of life, thought and the electricity within and between?

The impulse to clarify can move away from or toward an acceptance of the magic of the everyday, the random and mundane. The esoteric edge of things and our responses to them, shimmer a little when they do not quite line up. This awareness of the subtleties of dissonance is acknowledged by a diversity of thinkers over the last hundred years, from Walter Benjamin to Svetlana Boym and Hito Steyerl, among many others.

The nineteenth century brought the industrial revolution and with it the necessity to order time so that production could be measured, machinery and humans controlled. Memory escapes control as does the body which is synchronous with the elemental. The application of memory (and its correlatives imagination and intellect) to technology continues to create a dynamic between order and dissonance. That dynamic is the glitch.

In her 2020 text, Sleeping in the midday sun, Higgins considers the effects of music and the modelling of light and dark as these collide with subjectivity and acculturation. The random nature of reverie can open out such considerations, disgorging a different approach to the layering of knowledge and representations. This is a sideways and risky step yet one worth taking for it may marry up troubling, outmoded distinctions, or it may allow things to lay themselves out where they can be seen for the treasure trove of glitches they inevitably embody.

Writing in the early 1930s, philosopher Walter Benjamin noted: ‘He who has once begun to open the fan of memory, never comes to the ends of its segments…; that image, that taste, that touch for whose sake all this has been unfurled and dissected; and now remembrance advances from small to smallest details, from the smallest to the infinitesimal, while that which it encounters in these microcosms grows ever mightier. … Language shows clearly that memory is not an instrument for exploring the past but its theatre.’

The players in the theatre constructed by Anna Higgins are modelled outside the conventions of lighting and framing. There is no proscenium arch despite a generally rectangular format. Light both embellishes and wears away what it touches, creating illusions and allusions. The objects the viewer discerns pause momentarily, their edges disturbed, their presence somewhat diffident. Sometimes there are gestures glimpsed through smears of visual information. Water and air become thick, colour looms on the border of being tangible then recedes, elusive as sunlight on a cloudy, windy day.

Images are unmoored, become indeterminate. Then there is a pooling of imagery, sometimes a sediment. There is reverie, atmospheres, invention, adaption and no need to narrate. Expression does not necessarily require a story or clarity. Clarity can be like time, an invention for a specific purpose that tries to fix meaning rather than letting it go. Narrative implies the naming of things but if things represented are wilfully indeterminate, they can be silent, or if not silent then adaptable in their indications.

The theatre of still life, of the tableau, spills over ceaselessly. Each tableau or frame contains what film theorist Martine Beugnet has described as ‘an ocean of variables.’ In the past, still life as a genre was overlooked as it was perceived as not approaching the aggrandisements of history or portrait painting. Still life went in another direction, the mundane, small, humble, the domestic interior or garden. Daily life was stilled within meticulous detail.

More recently, the technological abilities of the analogue or digital, still or moving image to freeze and reflect life continue to be vaunted as paramount. But mistakes or glitches in these mediums and their processes, along with errors in the interpretation of any image are as interesting to ponder. Opportunities to work directly with hands, paint, and various instruments on those mediums born from technological innovations remain irresistible. Still life becomes still living, the frame becomes entirely porous, a useful and momentary container.

Memory, whether human or not, consists of layers which respond to internal and external stimuli. Memory has a physical, visceral origin. Combined with the tools available – in Higgins’ case these are analogue camera, computer hardware and software, and her own hands with their ability to paint and draw – memory responds. This dialogue of thought and feeling with materials is both considered and expressive.

Anna Higgins focusses on the pervasiveness of images, our inability to see them for what they are and our corresponding wish for them to be other. Embedded within her work is the catastrophic beauty of that wish. As we need water to stay alive yet we can also drown, as we need the sun to give us light and warmth yet the sun will destroy us if we disturb the interconnectedness of life. Gesturing toward the many and various obscurations in human perception, the enormity of such certainties is embodied within Higgins’ subtle works.

References

Walter Benjamin, A Berlin chronicle, One-way street, Verso, London 1998 pp 296, 314

Martine Beugnet, Introduction, Indefinite visions: cinema and the attractions of uncertainty, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2017 p 10

Svetlana Boym, Nostalgic technology: notes for an off-modern manifesto 2006 sites.harvard.edu/~boym/manifesto.htm accessed 21/01/21

Anna Higgins, Sleeping in the midday sun 2020 areadingroom.com/viewing-rooms/sleeping-in-themidday-sun/ accessed 21/01/21

Hito Steyerl, In defense of the poor image, The wretched of the screen, Sternberg Press, Berlin 2012 pp 31-45

— Judy Annear, 2021

Judy Annear is a writer, researcher and Honorary Fellow at the University of Melbourne School of Culture and Communication. She lives in Victoria, Australia on the land of the Dja Dja Wurrung, whose sovereignty has never been ceded.

Anna Higgins’ image-based practice incorporates found archival and contemporary material that is abstracted and re-contextualized through methods of collage, painting and film photography to form new perspectives and poetic interpretations. Anna’s work explores the nature of images and how the mind makes sense of visual information that is not fully formed.

Anna completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) at the Victorian College of the Arts (2013) and a Graduate Diploma of Museum Studies at Deakin University (2016). She is currently a student of the post-graduate program at the Royal Academy Schools, London. Recent solo exhibitions include Faraway Beach, Mackintosh Lane, London (2019), The Sick Rose, David, Melbourne (2019), International Waters, Centre of Contemporary Photography, Melbourne (2016) Double Negative, Substation, Melbourne (2015), Ma, 3331 Chiyoda, Tokyo (2014) Super Panavision, West Space, Melbourne (2014) and Higgs Boson, TCB art inc, Melbourne (2013).