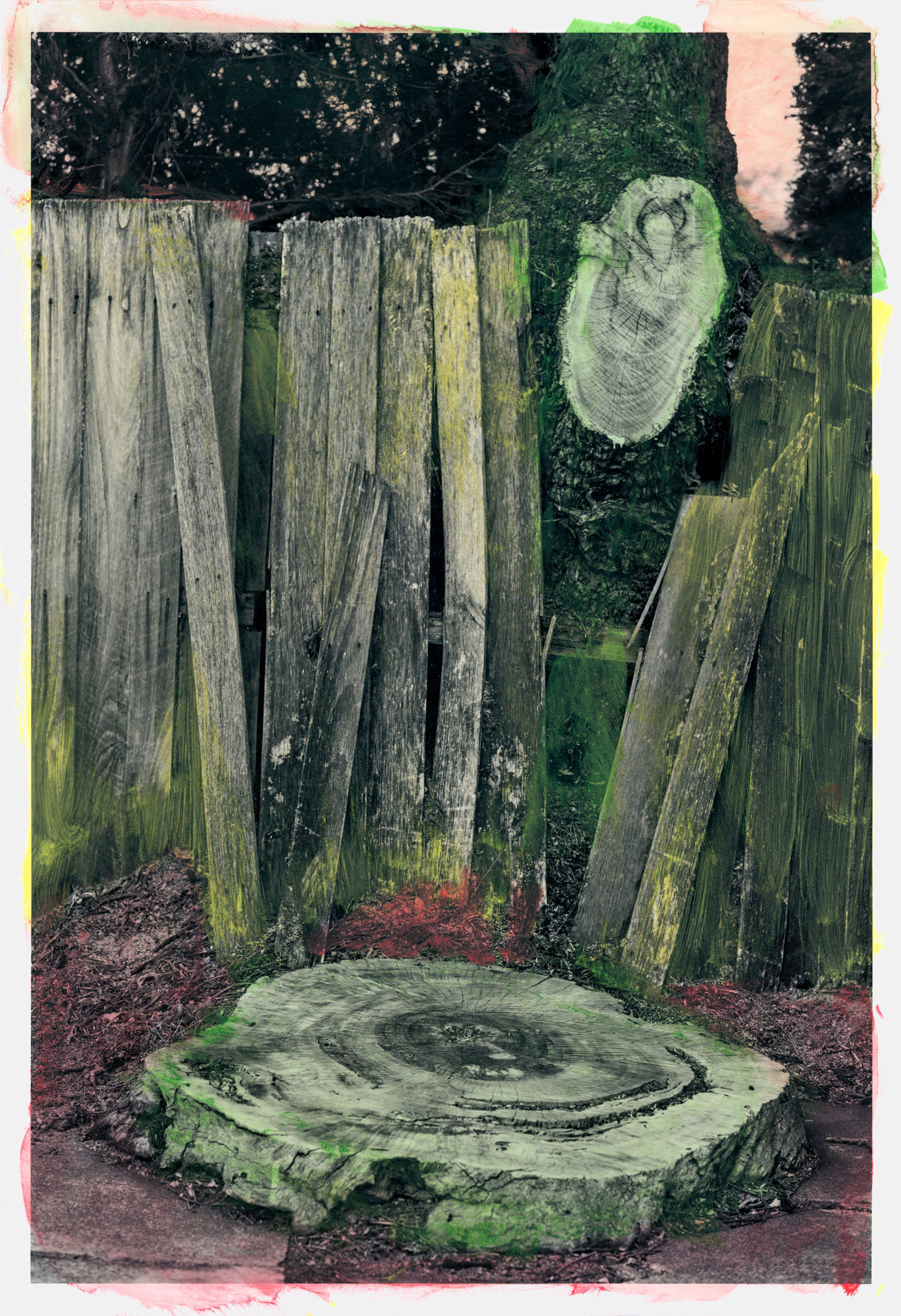

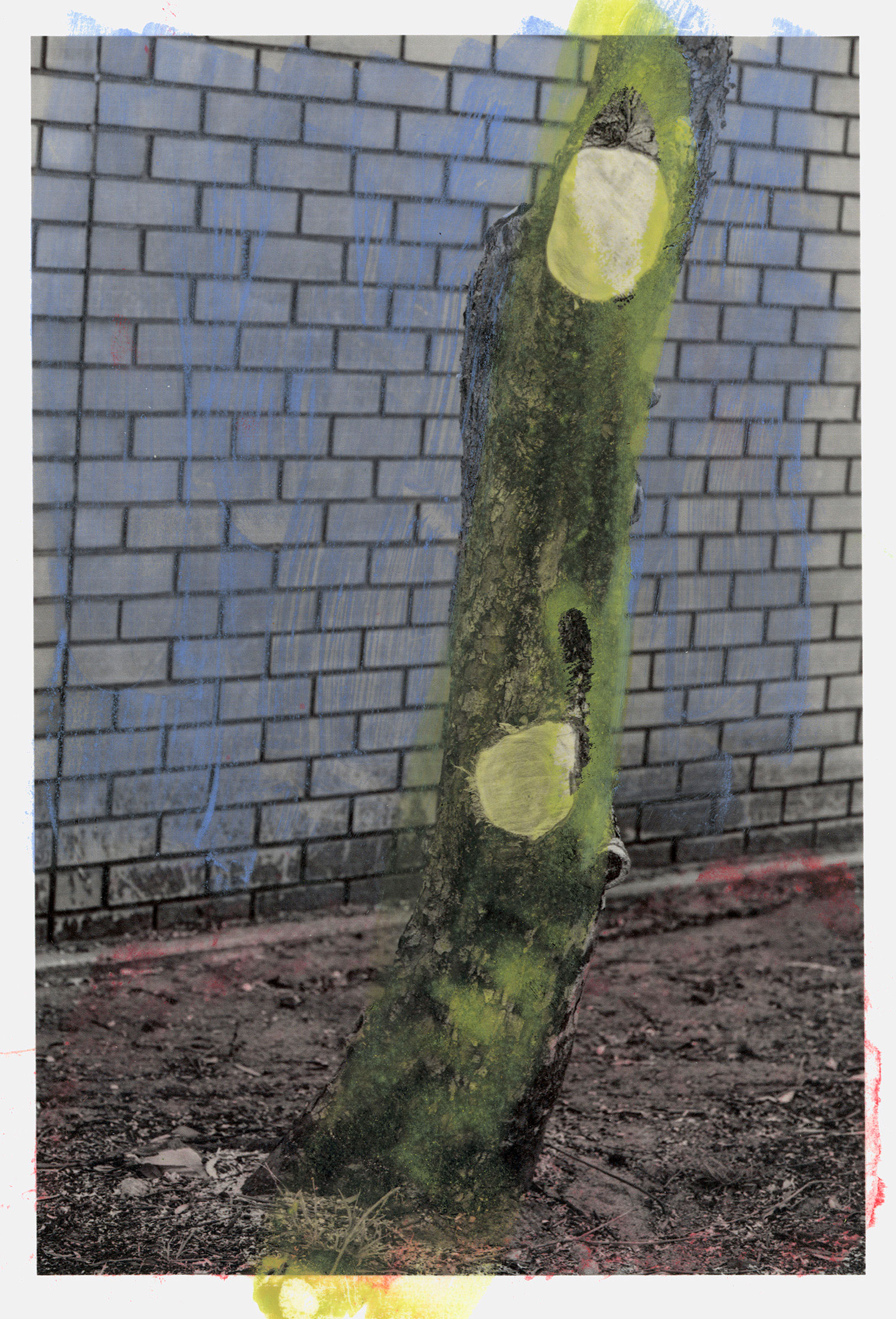

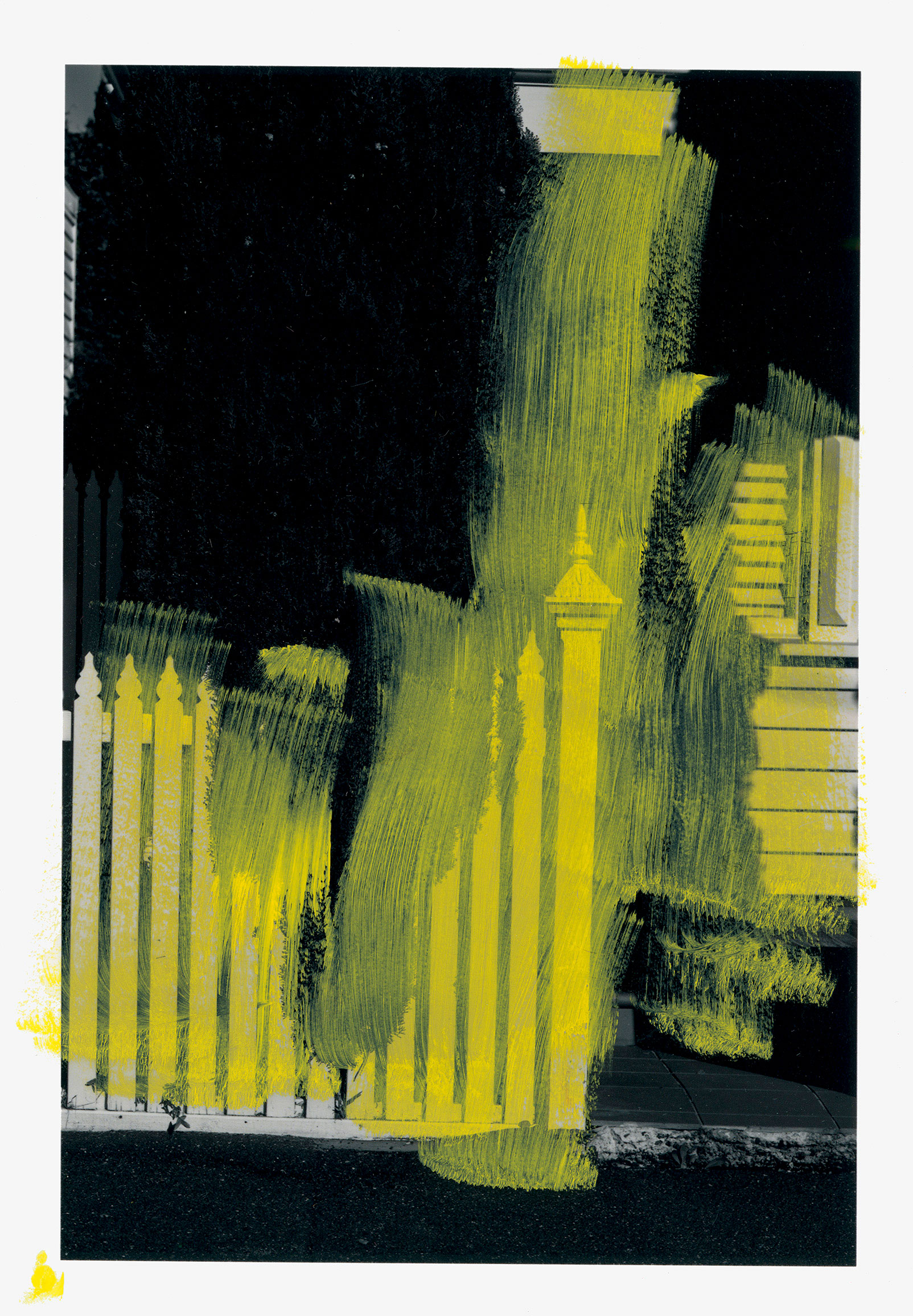

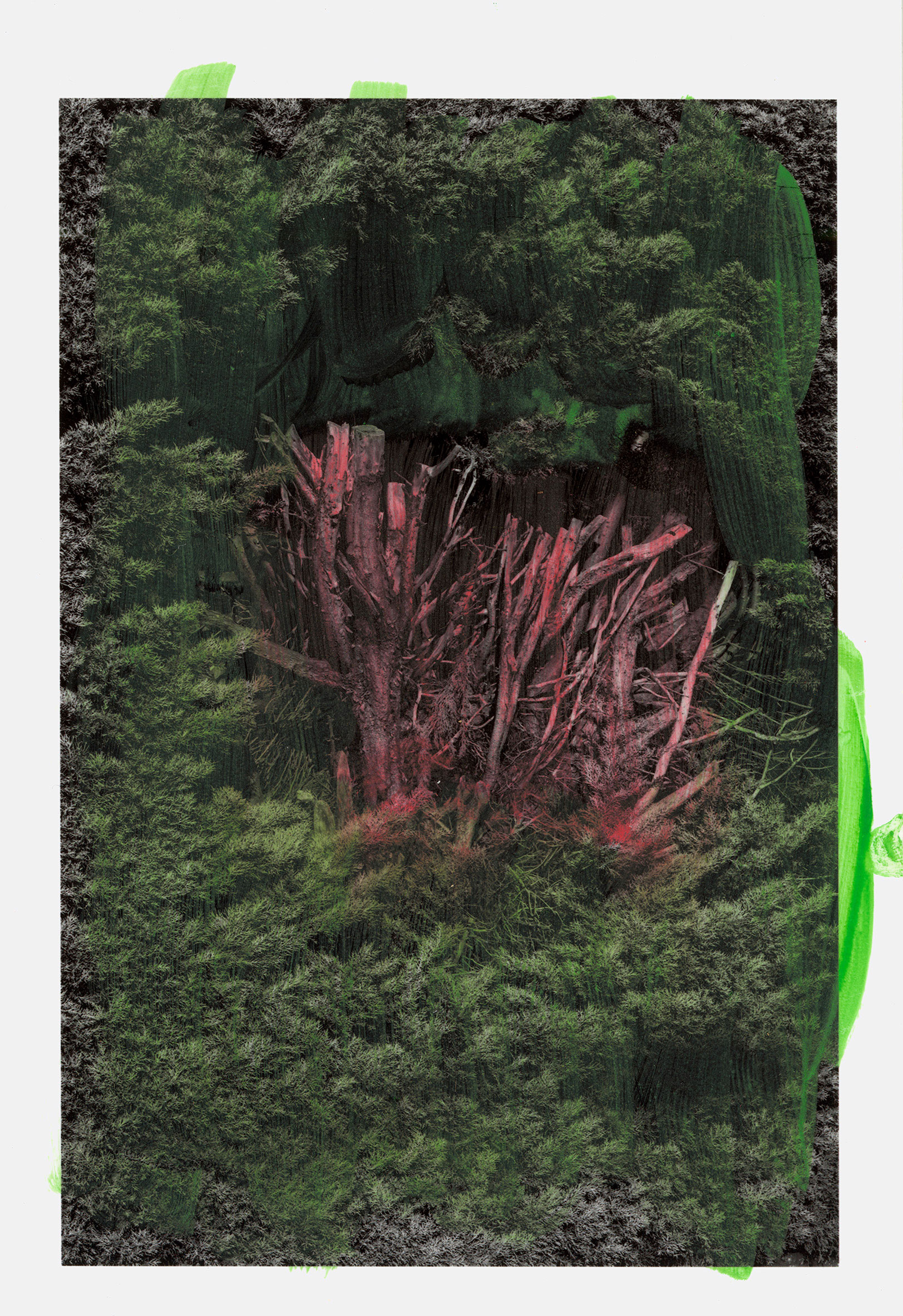

Trees and Fences

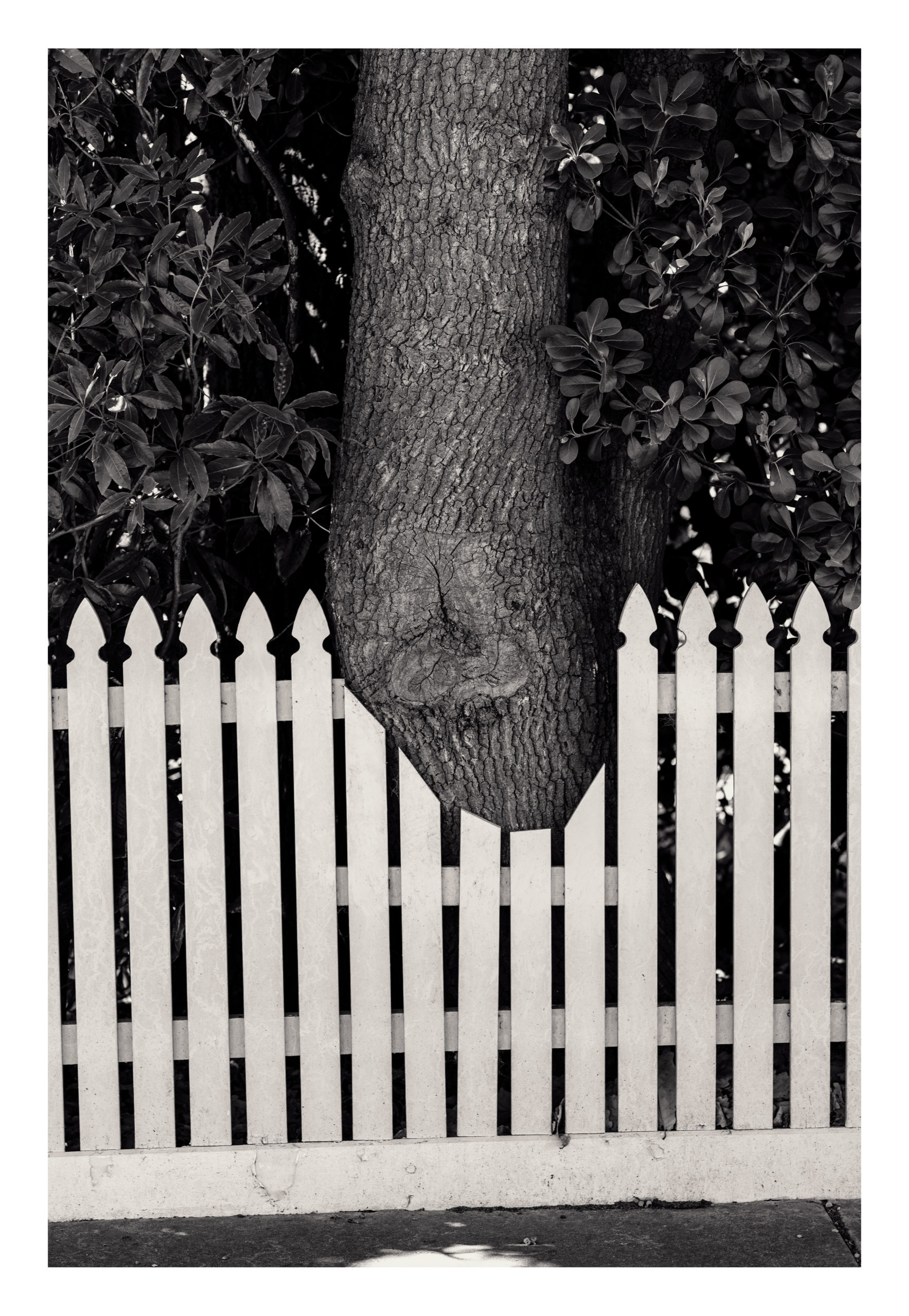

Geometries of segregation are also bodies in the world.

The trees as tall below as above strain for the centre

Of vanishing waters as they do for the sphere

Of the sun. Yet at the earth’s core there is liquid fire

Gusting like the echoic heart of stars; in the heights

There is the cosmic void. Life makes its place

Between. Before there was life there was no

Place for life, but the pulse of return to intensities

Of zero are open in the heart of the order

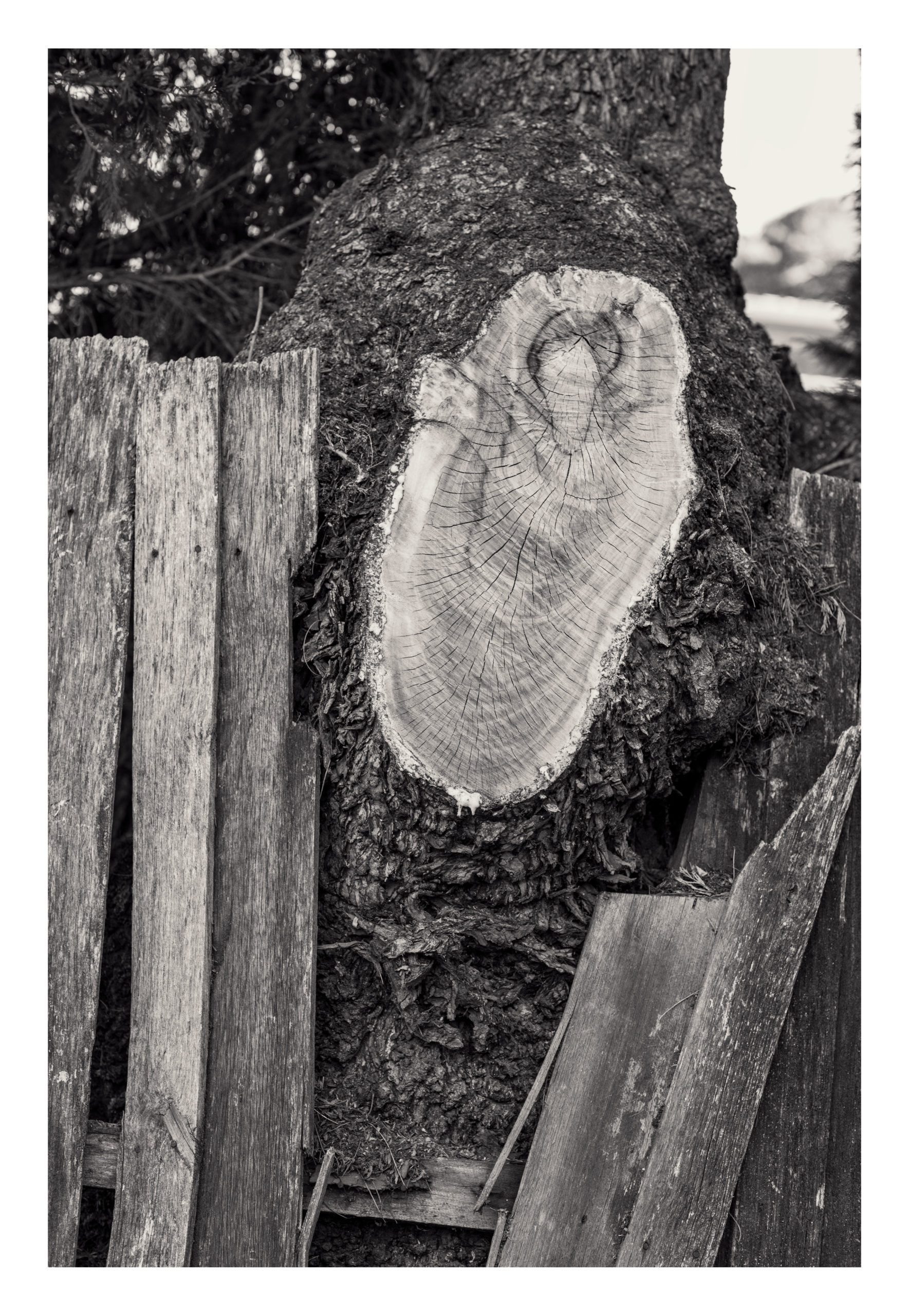

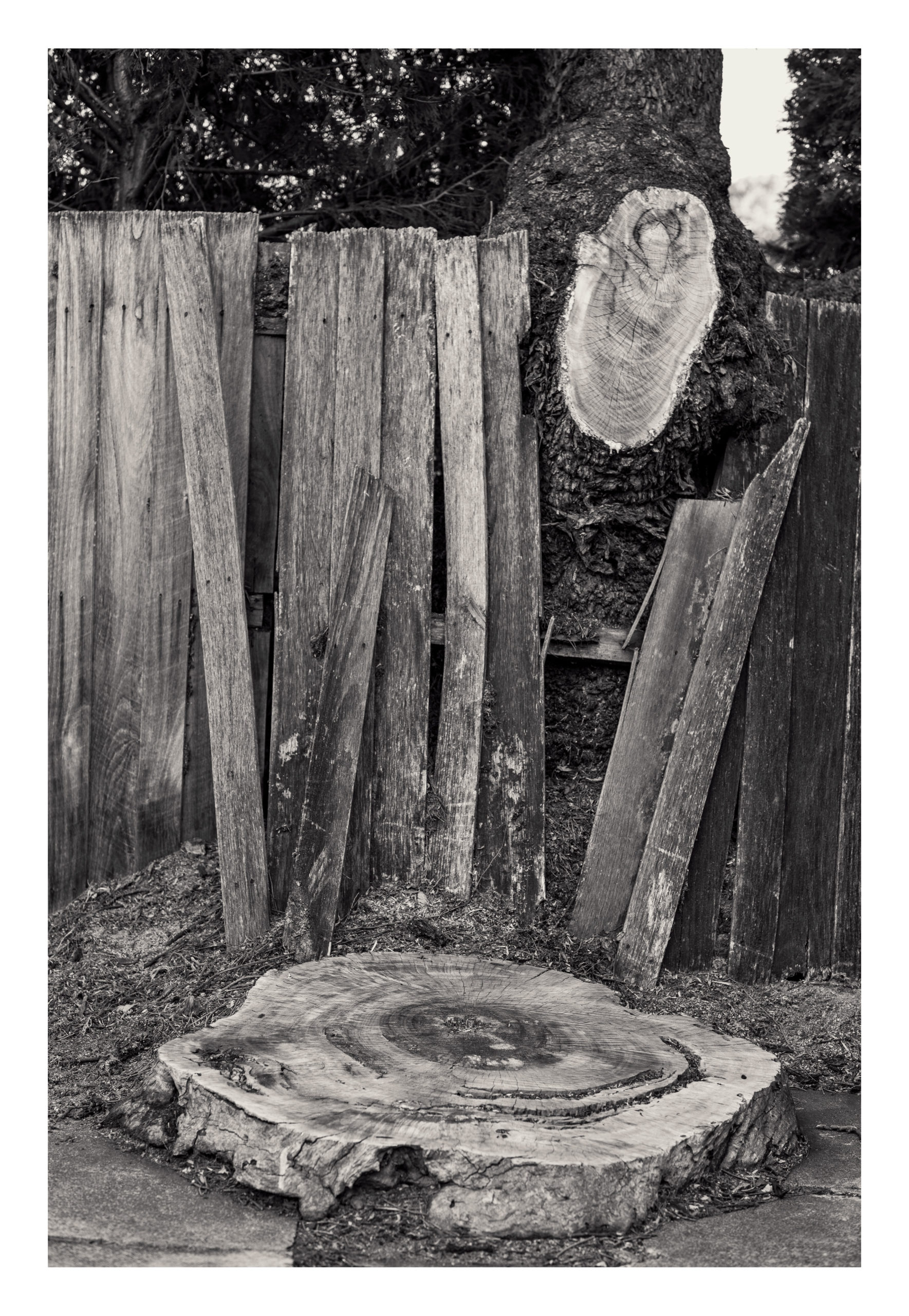

Of the living. Cut the dead into planks and lines

That cut the earth into property flat as domination.

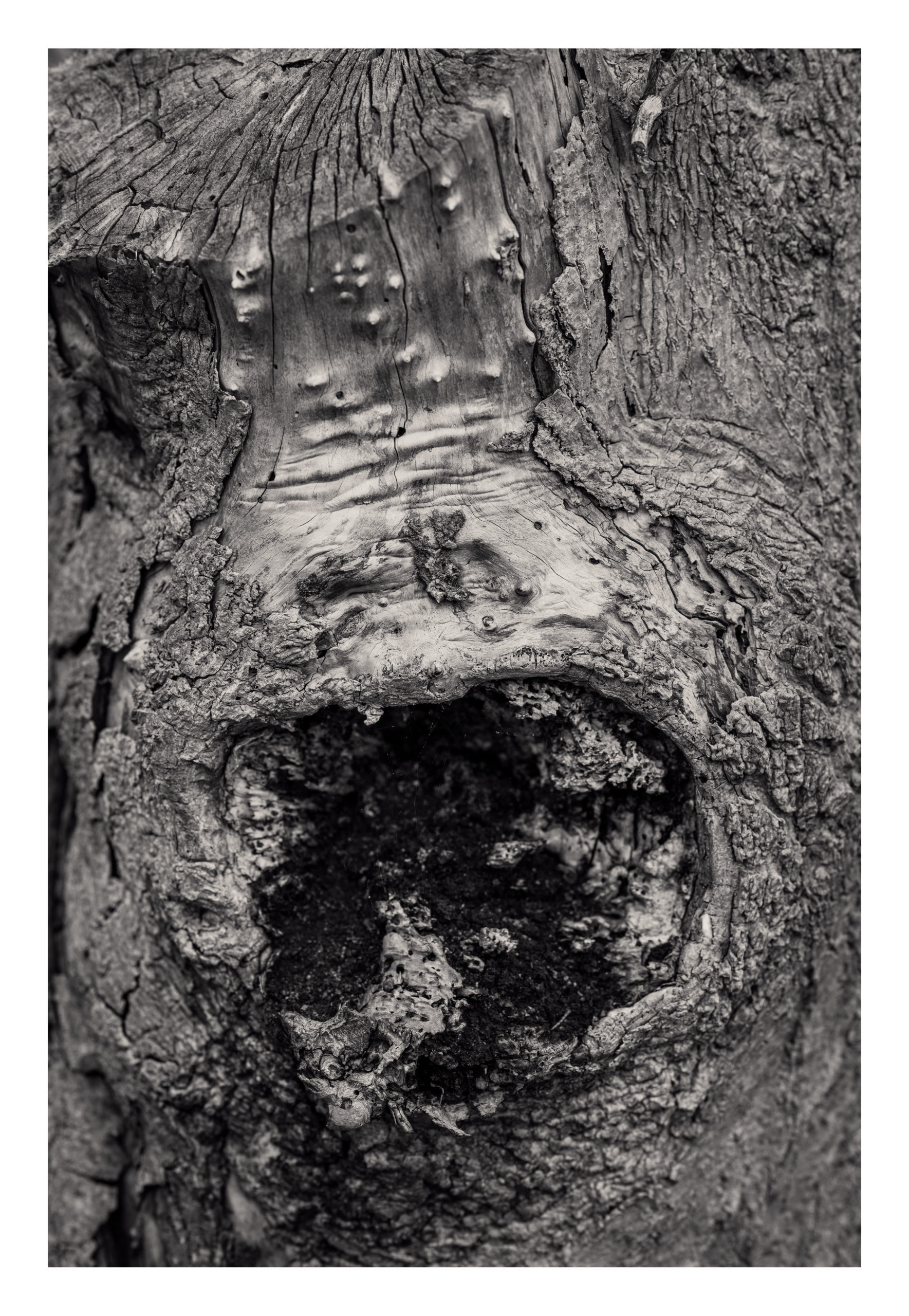

Knobbed and nippled in the accidents of growth

The form resists the form of the species that needs

What it puts to use, roots against triangles, cracks

Whispering of the ends of man, the severed limbs

That limbo in the delineations and lineages

Of a mental monkey’s dreams, spongiform eruptions

And unequal rings buggering the slats that lap

The forces of immanence, the planetary thought

Of self-stilling nomads distended like a flash

Of fur and favour caught between flame and nothingness.

Monsters of energy weave their virtual engines,

Unwavering seizures of parts and particles of dirt.

The measure of the earth is mantic as mathematics

In the polities that wrap each vegetal irruption

In these well-wrought leakages, the rage of scaffolds

And nets, the hunter caught in the traces of its tracking,

Hedges rifting in the galaxies of warring dice

Where the numbers clash. The light cracks into wraiths,

Into the makers of masks, of optical devices, tragedies

Of shadows, of the goat-hide stretched between branches,

The psyche that is not the breath-soul itself but the icy skia

Of uninvited guests. The festival takes place in the place

Of doubled and drunken shadows, in a split scene

Of time and timing, in the loss of time, as crisis.

We are images in a constellation of crises,

Each one bearing both on this momentary part

And on the straining hunger of the missing whole.

—Justin Clemens

Justin Clemens is a writer based in Naarm/Melbourne. His most recent book is Limericks, Philosophical and Literary.

It’s possible to walk

And step only on the bits of a certain pattern,

But then you can’t help wondering how it feels

To go on the other bits only.

– Margaret Tait. Responsiveness (Poems, Stories and Writings)

Circumlocution seems the only option when trying to describe the many different ways Yanni’s photographs affect me. All the accumulative words, phrases, and metaphors available to me now and into the future infiltrate my memory and thoughts – and then this only manages to scratch the surface. Did Yanni know this when he first asked me to write a brief piece about his photographs, I wonder? For years, I have had an A5-sized leporello presentation of seven of the photographs of trees and fences that I have regularly placed in different parts of my home studio. A leporello standing on its own is much like a fence, and, this is the basis to my somewhat elongated but always enthralling journey with these photographs standing self-contained before me, day in and day out. I need to write about Yanni’s personality, I thought at first, to find some wiggle space and come at things a bit differently, allowing for brevity and unconventionality to enter as required. For I do find Yanni has a unique personality and this somehow connects to the way his photographs do what they do for me. Mentioning the character of an artist is not considered crucial when mounting an ‘appreciation’ of their work; but I cannot deny that I also think about other photographers, specifically, and in the case of street photographers especially, in this way. Say for instance, Wols and Weegee (funnily enough both pseudonyms with the same first letter) who are longtime favorites, and also, of course, Helen Levitt, another great favorite, and all of them demonstrated in different ways quite unique personal leanings and identities. Not that I have met any of them or got to know them personally like I know Yanni, but drawing from biographical material and filling in the gaps through a persistent and in-depth acquaintance with their work, I found each had, like I find Yanni has, for want of a better term, a rather special personal swagger, not in the ambulatory sense so much as in the way their eyes and in turn their personalities move about and through the streets and world at large.

To continue on this personal track: Most of my adult life I’ve lived in various parts of Europe returning to Melbourne the place of my birth, for visits and sometimes longer intermittent periods. A close friend and one-of-a-kind singer and artist, Anita Lane, who sadly died this year, invited me during these visits to stay in her ancestral home in the leafy suburb of Glen Iris (notably right next to the suburb where Yanni lived as a kid and where he would later return to begin the Trees and Fences series). Anita moved back to the house where she was born and raised up in (we’d joke ‘let down in’) after years of living in other parts of the world. Wandering around the strangely familiar but also haunting streets of suburbia with Anita as an adventuring cohort produced particularly revelatory and poetic observations, and, which I now see, are reminiscent of the kind of observational sensibility and perspectives these photographs of suburban trees and fences also wield. Seen through both Anita and Yanni’s eyes, the suburban landscape harbors and propagates a paradoxical kind of imaginary life. It’s a matter of looking hard at things that usually resist or evade such hard-looking and to allow for hidden patterns or cues to appear. Patterns or cues accompanied by subtle and beautifully ironic leaps of humor or pathos. All of which would never emerge in quite the same way if not from such specially outfitted and tuned personalities in their ambulatory encounters with everyday streets and objects.

Musingly looking at these photographs of trees and fences caused me to recall the following well-known statement from Jean-Jacques Rousseau: “The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not anyone have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows, Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.” Aren’t the particular spatial confabulations and inexorably slow tussles being played out between nature, represented by the tree, and property, represented by the fence, in these photographs, illustrative of Rousseau’s argument against claiming nature for one’s own? That in suburbia with all of its comforting banalities and slight deviations we can observe the somewhat warped, myopic, and ultimately unhappy consequences that claiming to own property has both upon humans and the world?

Serendipitously since I live in Brussels, I was able to stumble upon a Belgian artist whose work connects ancestrally and spiritually with Yanni’s Trees and Fences series. For Jacques Lizène in the early 1970s practiced a ‘subversive’ version of street photography that was titled “View Along the Bottom of the Walls [ Regard au bas des murs]”. Each black and white image in the series shows the bottom part of a different suburban wall where it adjoins the footpath, and there is much to think through and about with the application of such tightly fixated blinkers (also slang word for eyes). This is part of a larger body of work that Lizène called “The art of the suburbs (the suburbs of art) [ L’art de banlieue (la banlieue de art]” and with which he wanted to hold a mirror up to what might be deemed a very depressing environment and about which he exclaimed: “don’t be weighed down with the misery we live in but point at it and smile.” Yanni’s Trees and Fences series also delivers a subtly subversive and conceptual retake on the genre of street photography. One concentrating our attention in a luminously blinkered way onto this very particular part of the world, and, in spite of such limitations, or because of them, provoking many wry if not sly smiles along the way. Another cause of levity arrives by considering these photographs from the perspective of a dog. For trees and fences hold a special urinary and in turn olfactory attraction in the canine world, add to this the knowledge that Cézanne was known to declare, but most importantly demonstrate, that to be a good painter one should view the world the way a dog does. Rilke recalls how a certain Mlle. Vollmoeller observed Cézanne as “He sat there in front of it like a dog, just looking, without any nervousness, without any ulterior motive.” We can only guess what the ‘it’ was, whether a landscape, a person or an object but it’s the very ‘thingness’ of what lies in front of the painter that he’s fixated on. And it is the quality of thingness to trees and fences that leaps to the foreground in Yanni’s photographs, and, with it an intensity of looking from which the photographs were born and which is brought forth in the viewer. Again, to Wols an extraordinary photographer and painter whose 1930s photographs of street pavements are for me touchstones in all this, who stated in his book of aphorisms: “If you managed to look into the very heart of a thing you would see that it is the same as your own self’s.” The philosopher Jane Bennett refers to this form of attention as ‘thing-power’ and she explains that it involves an attentiveness to the vitality and vibrancy of all human and non-human things. In these photographs of trees and fences one senses the energetic vitality of things; things usually considered to be inert matter but instead here becoming vivid entities and ‘vibrant matter’ existing outside the context or role humans have given them. Not forgetting that trees are quite special things as much as the fence-makers of the world might or might not wish us to believe. For recently it was discovered that through underground fungal networks, trees are able to send distress signals about drought and disease or insect attacks, and other trees alter their behavior when they receive such messages. This hammers home the fact that a tree always possesses a capacity for arboreal solidarity and existential resistance beyond and in defiance of the many above-the-ground constraints, barriers or dangers placed against or before it.

All this offers many segues and openings for further speculations about the before and after lives of these photographs and the things therein. Something that users of this photobook must strike upon and experience from within their own particular inclinations or needs, as the photobook historically, with its proliferation of imagery and distinct designing, invites participatory and ludic modes of entry and circumnavigation. Finally, to mention two statements that appear at the end of different essays by the Belgian ‘encyclopedic thinker’ of photography Henri Van Lier, and, which are intended here as mere indicators or starting points for further unfettered circumnavigation around and circumlocution about this new photobook by Yanni. At the end of one essay Van Lier writes: “Invented and used by earthlings, the photograph is the stuff of extraterrestrials.” Another essay concludes with the quizzical statement: “Labyrinths were paths almost always without exits. Photographs can lead to anywhere but lack paths.”

—Marcus Bergner

Belgrade/ Brussels, December, 2021

From the forthcoming book Trees and Fences, Yanni Florence

Marcus Bergner has exhibited his work in experimental film and sound poetry throughout Europe and Australia. He is presently preparing the publication of a collection of his drawings/designs as well as curating the touring program of films by the Australian artist and musician Lee Smith.

Yanni Florence (b. 1965, Melbourne, Australia) co-founded, edited and designed the seminal art publication Pataphysics Magazine (1989). He completed a Bachelor of Architecture at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (1997). Yanni has been making and publishing photographs since 1990. His monographs comprise thoughtfully nuanced and sequenced selections of images. Yanni’s work has been included in several group exhibitions, including Melbourne Now, National Gallery of Victoria (2013) and NGV Triennial, National Gallery of Victoria (2021).

His first solo exhibition, Tram Windows, was held at ReadingRoom in 2019.

FLORENCE, YANNI, Trees and Fences, ReadingRoom, Melbourne, 23 April–21 May, 2022

With thanks to Trent Walter.