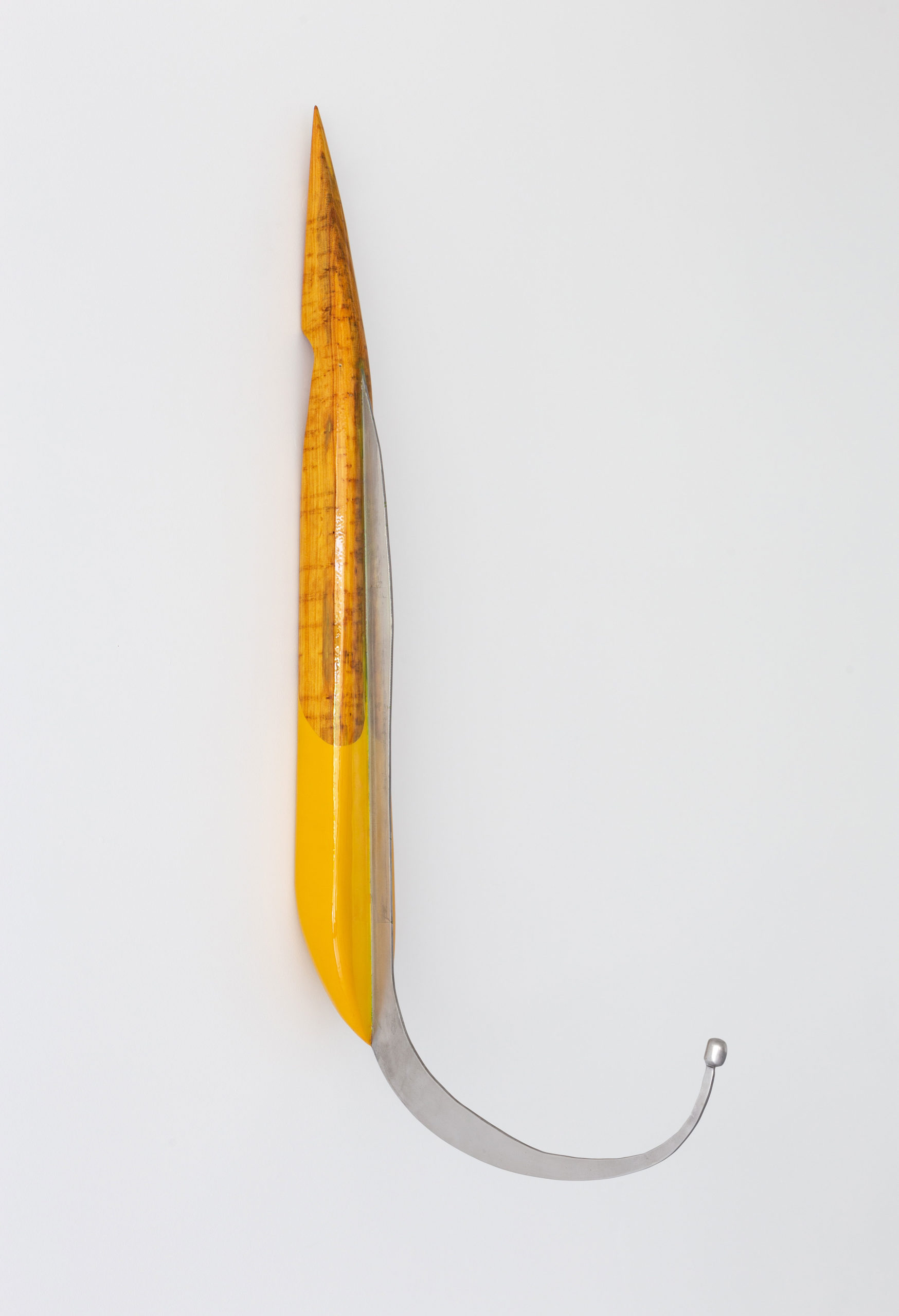

Quantum Rain Drop, Clog Spirits

I feel the need for speed, quip or manifestation for travel faster than sound and /or the denial of one’s potential for stasis.1 We mis-quote Cruise as Maverick in Top Gun, while waiting for the military acceleration of capital and progress to slow down.

Waiting.

To be clogged implies a blockage. Stopped. Something is in the pipes. The clog is a wooden shoe we associate with the Dutch: historically carved, traditionally from poplar and contemporarily emulated in, and as style, by Birkenstock, Prada, Wang and Sander et al. Protection, practicality and the potential for a passing fancy.

Since meeting with Jim Roche a few weeks back to discuss the work for his exhibition, I have been thrown into strike action at the art school inside the university where we first met. It is the same art school where the artists and their histories (lived and learned) I have been in conversation with for some twenty years now, have also attended, passed through, or referred out of, and into the world. These conversations are move between the specific and generalities in form. The work produced, and the work made, might comprise the language of images shared, artists discussed, politics encountered, sub-cultures lived. Its subsequent is desire morphed by all manner of material. This work, becomes a site for further conversation — an iteration of iterations, a cosmos of questions and speculations, both of what is shared and yet to be known. Masato Takasaka has analogously referred to this as the fourth and now fifth dimension.2 I sometimes think it is only quantum that can conceptually frame the relationship artists have with all the things artists have relationships with. My imaginary physics, the loop symptomatic of this system, is both black holes and light speed.

Over the last few weeks, I have been looking at surfboard and skateboard designs, Richard Tuttle’s Chapter and Heads, Ron Nagel’s libidinal, humorous and fluid ceramics and the voids created by Richard Grosvenor’s epic post-minimal mechanical, and industrial architectures that exist as stealth-bomber-echos. GT stripes elude to class and trace what we think to be a known form – the C-2R Le Mans motor, a 1965 Ford Mustang or a Datson 180b, narrate a relation to the carefully carved verging on the absurd, elongated clog and ski forms I saw in Roche’s studio. Carved from poplar wood collected from cut-down trees in the Melbourne botanical gardens by gumtree-ers reselling stacks on eBay, Roche’s forms hang, memento-mori-like-futurism — clogs time has stretched, striped and resin-ed.

I have also been diving in and out of the Dale Hickey sections in David Homewood’s Painting the banal: Dale Hickey and Robert Hunter, 1966-1973. In this writing, a PhD dissertation, Homewood sets up a specific set of relations: artistic and literary, conceptual, and formal, chemical and mystical, between two artists at a very particular point in time in Melbourne. The specificity of this time is of course in relation to ideas circulating in art at the time globally. And importantly, Homewood refers to Hans Belting’s essay The End of the History of Art (1987), and the argument that despite the homogenising effects of globalisation, there is a strong rationale for art history’s continuing preoccupation with local traditions.3 Homewood goes on, that even in a world of disappearing boundaries, he explains individual positions are still rooted in and limited by cultural traditions. Belting’s adoption of a global perspective is based on the presumption that ‘today only provisional or even fragmentary asserts are possible”.4

I am thinking of an exhibition of fence structures used by Dale Hickey at Pinacotheca Gallery in 1969. In a conversation with James Gleeson, Hickey recalls: ‘(it) consisted of typical suburban fences actually constructed around the walls of the Gallery. It really extended my interests in repletion… (sic) and well boredom, I guess’.5 Hickey continues elaborating on his interest in the suburban imagery we have come to know him through, quilt patterns on beds, and also as Gleeson describes, “that although it had superficial similarities with The Field style of work” it didn’t regard the surface with the same sort of integrity.6

Hickey goes on to explain that in conversation with the history of painting, and the commitment to its faith, could he evoke the same kind of feelings three-dimensionally as he had been doing two dimensionally. The Fences exhibition, somehow being viewed “grossly surreal” as opposed to the decorative response found in his paintings. Ordinary objects and formalist abstraction. Homewood suggests that “Hickey’s defamiliarsied depictions of kitsch objects were meant to occasion an experience of the transcendent.” 7 This aesthetic defamiliarization, Homewood goes on, is intended to transform familiar things into near unrecognisable entities, communicating a state of awareness, or detached contemplation, belonging to an irrational mode of experience.8

Marja, Nelleke, Van Der Zande and Reno, could be the names of family members, a GoGet Fleet in Flemington, or special release sneakers by Hoka. Roche’s forms are neither skis nor clogs, bearing names that we would normally associate with life forms, they are hybrid intersectionals. Kitsch wall hangings from tourisms cultural and generalised forms, his Grandmother’s porch, John Nixon paintings or Vincent Fecteau sculptures. Material translations true to form, but randomised function. (Roche’s last work riffed off the materiality of fibreglass, and post-formalism such as Stella). Homewood refers to a reading of Global Conceptualism where localities are linked in crucial ways but are not subsumed into a homogenised set of circumstances and responses to them… a multi-centred map with various points of origin in which local events are crucial determinants.9

I am thinking of Lewis Fidock and Josh Petherick’s U (2019), or Torch and Wreath (2016) or, more recently, Make a Wish (2023). And, while there is a sense of the macabre or ominous ending generated by the scale shift —oversized almost theatrical, but yet still minimal, leaves and screws — which renders us, the viewer, Monster. It is this aesthetic defamiliarisation that is shared. Roche’s approach is in the subversion of this graphic feel for the need for speed and the physicality of the length in time, and with Nagel, Tuttle and Grosvenor we find a similar materialised temporal shift to which Homewood refers to as the occasioning the experience of the transcendent. Bio-logarithmic iconographic histories, formalisms, fashion and family — pull focus, compress file: quantum rain drop, clog spirits.

—Lisa Radford, 2023

Lisa Radford is an artist and writer.

1 Tony Scott, Top Gun, 1:50 mins, 1986

2 Masato Takasaka, in various conversations, 1997-2023.

3 Hans Belting, The End of the History of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), xii. Also see David Summers, Real Spaces: World Art History and the Rise of Western Modernism (London: Phaidon, 2003) in David Homewood, Painting the banal: Dale Hickey and Robert Hunter, 1966-1973, University of Melbourne, Victoria, 2019, p.32

4 ibid, p.32

5 James Gleeson Interviews: Dale Hickey, 01 May, 1979, https://nga.gov.au/media/dd/documents/hickey.pdf, accessed 27 August, 2023

6 ibid.

7 Homewood, op.cit, p.16

8 Homewood, ibid, p. 46

9 Camnitzer, Farver and Weis, Global Conceptualism, 1999, vii in Homewood, ibid, p. 33

Jim Roche (b. 1989 Gold Coast, Queensland) is a Naarm / Melbourne based artist, working predominantly in painting and sculpture.

Recent solo exhibitions include Smile, Savage Garden, Melbourne (2022) and Scrambler, Cathedral Cabinet (2022). His work is currently on view in the group exhibition Ümwelt, curated by Jonny Niesche, Starkwhite Gallery, Auckland (September, 2023); and has been included in group exhibitions at ReadingRoom, Melbourne; Daine Singer Gallery, Melbourne; Haydens Gallery, Melbourne and Melbourne’s Living Museum of The West.

Roche’s works have appeared in Russh Magazine, Teeth Magazine and he has contributed artworks for Hoddle Skateboard company. Roche was commissioned by the University of Melbourne to create new work for the 757 Art Project (2019).