Inoperative words #1

Tom Melick

23 May, Sydney, 2:41 pm

maps

calligraphy

cuneiform inscription

graffiti

lacework and netting

botanical shapes

musical composition

weather systems

cartoons

signatures

children’s drawings

anatomical illustrations

architectural plans

electrograms

I made the list on the train, after talking with my friend Nina about Mary’s art. It comes from wanting to read her pictures, piece them together from clues and associations.

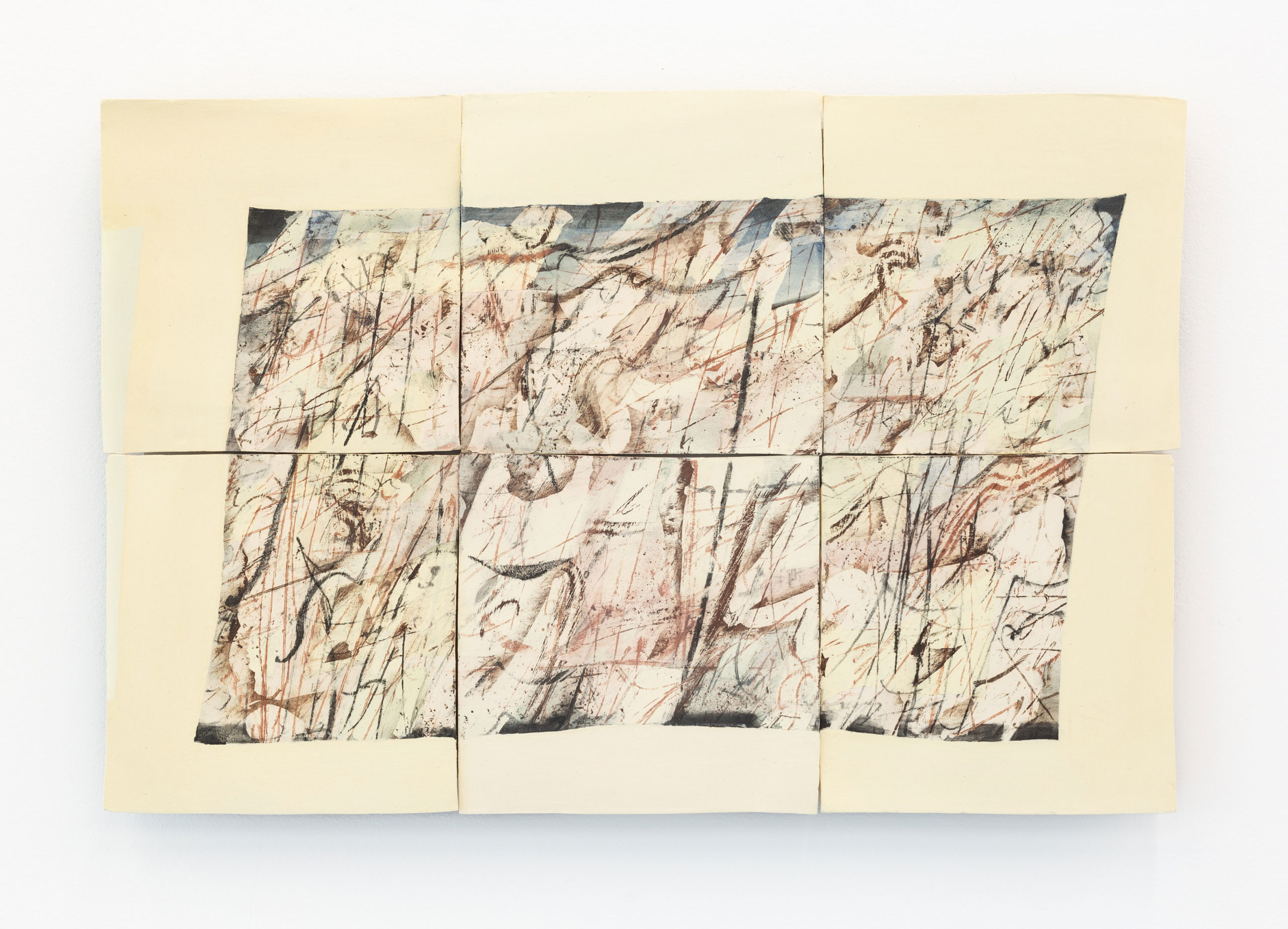

The images ask for guesswork because what is absent is just as present as what appears. Her visual language is never one thing, refuses a single technique even. Some hair-like marks suggest script (ideograms?) but then breakdown, become excitable. Nothing remains still.

I was trained to locate artworks in time, secure them to a particular style. Art history is a discipline of explanation and emplacement. Mary’s pictures bother chronology and style. They come with a restless historicity. Full of citations to visual languages that lead you across the surface, but also into the primary act of mark-marking.

You once wrote that when there is too much to say you synthesise it into something cryptic. You were referring to your own writing, but I wonder, can this also be a way of making images?

Abstract not in terms of its art historical meanings, but something closer to the word’s etymological root? “To draw, drag, move” away.

Elisa Taber

25 May, Montréal, 9:21 am

Mary’s marks graze their surfaces like absolute decoration, emancipated from every purpose. They feel “al ras de suelo” (grazing earth). The Uruguayan storyteller Horacio Quiroga describes his characters that way, hovering between life and death.

Intent is a raft moored to the island that is comprehension, always trying to float away. She cuts the cord and speaks to herself. Brave isolation.

I stare and stare at the clusters of shapes until they emit smoke. This is fiction, I think and imagine a mask beside a featureless face. Reality’s doppelganger, unlike dreams, is not dispelled by but points to its artifactuality. I fall deeper into sleep.

A snake slithers up a stairwell to a room in the sky, swallows a star, and falls so hard it becomes a rooted tree.

Air dense with swarms of no-see-ums blown clean by a wind that feels like diving into a tepid pool.

An arrow points to the sea, “No one lives there, they drowned.”

Those are the myths, stories of origin, I see in “Ceramic Papers.” Dwelling on her encrypted script, I peer into her home. We can only hear each other. You mention a “restless historicity,” maybe this is the time of myth: the primordial is immanent, now gods descend in human form.

Inoperative words #2

Tom Melick

6 June, Sydney, 9:51 am

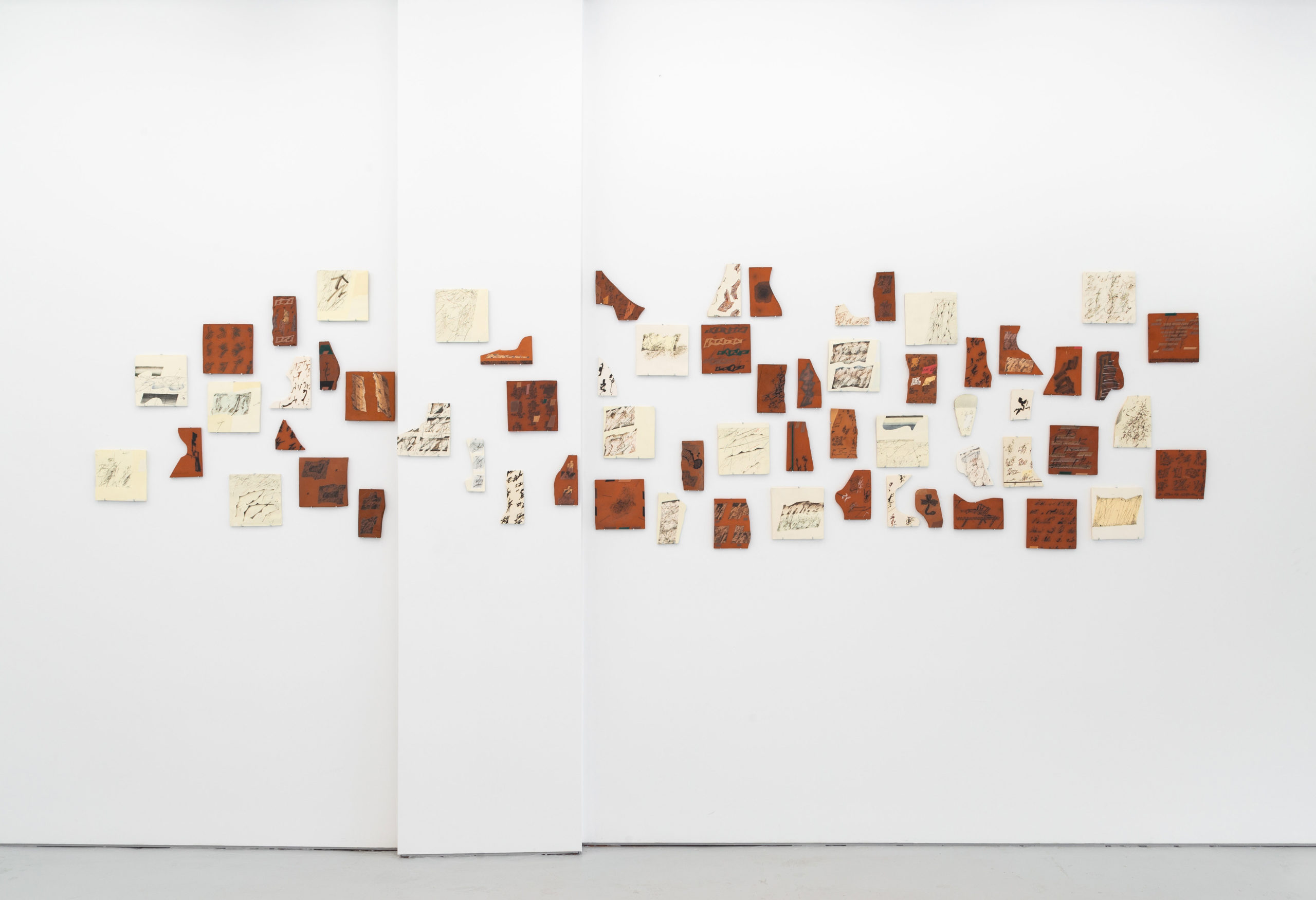

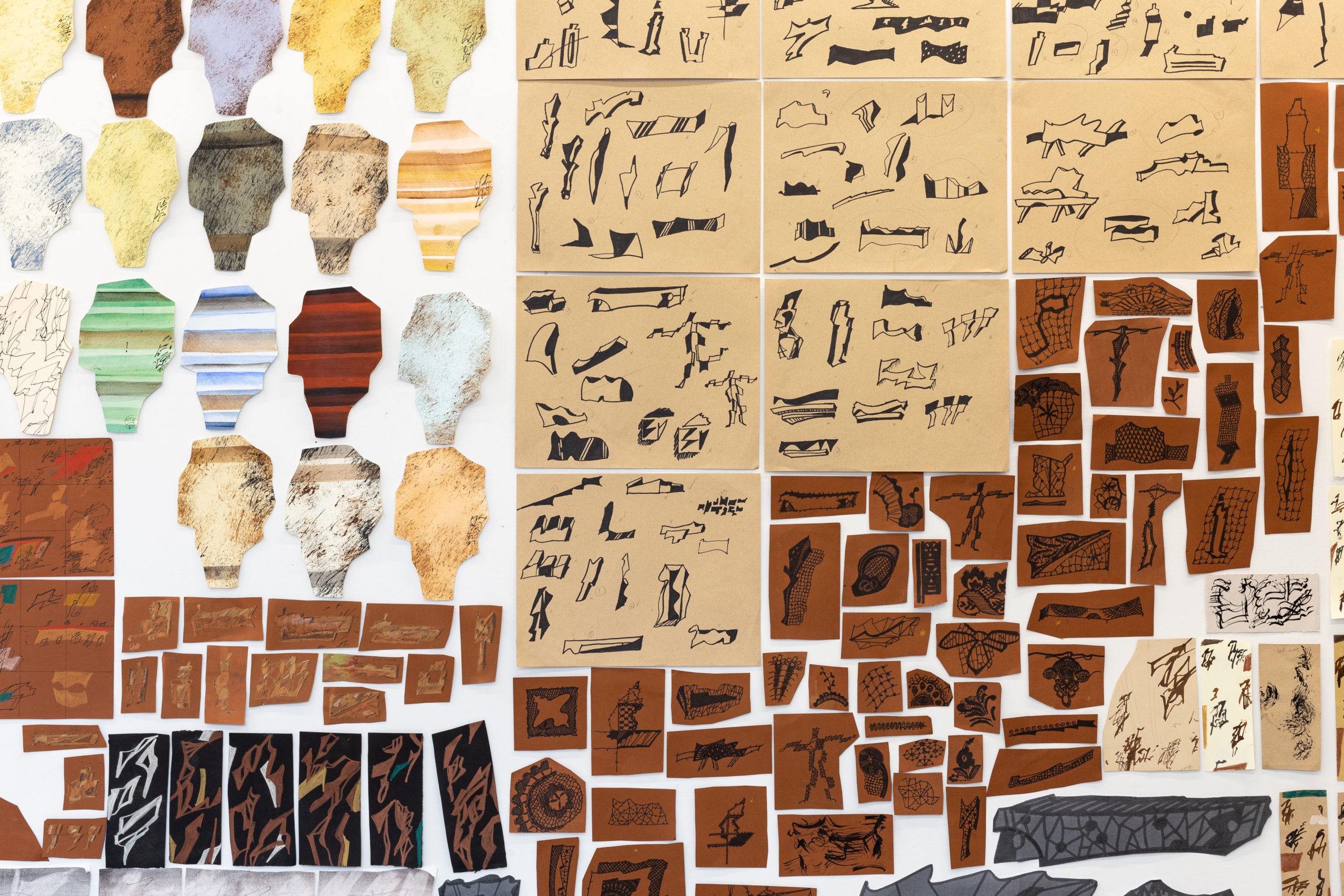

I’m drawn to the abundance of Mary’s process, the volume of work that goes into the making of the artwork. This method is usually hidden under the surface, but in “Ceramic Papers” we get a glimpse.

Her home is filled with folders and books where these scraps collect: drawings, notations and word lists, colour tests, reference images, shapes cut out from cardboard and fabric. Most are small, no bigger than a child’s hand.

On a windy day like today, when the windows rattle, it’s easy to imagine a sudden gust of wind whooshing through, like Hokusai’s picture of Tōkaidō road the papers go flying.

Wind is a vital metaphor for this reason, because of its disordering quality. Can make you feel crazy, the wind! The way it jumbles thoughts and things, carrying them elsewhere.

Aby Warburg noticed hair and garments and other windblown accessories in Renaissance art and thought of them not as decorative vagaries but as the afterlife of antiquity.

Images move; find ways of getting around, can even come back from the dead.

What’s happening in this exhibition? I think it has something to do with the dissolving of the study, the test, and what gets titled and shown as the finished work. Trying to hold onto that distinction is unhelpful, we need another way of orienting ourselves.

In Hokusai’s picture, Mount Fuji is drawn in the background as a single line, still as can be, while everything else risks being blown away. How many times did he look at that mountain and draw that shape?

What gets called a method, a process, is an obsession that comes with needing to work something out. It holds you in place until you and it become indistinguishable. What’s Mary’s Mount Fuji? A silly question?

Elisa Taber

7 June, Montréal, 7:07 pm

How do you create a language? Attach words to things and remember them. Memory of a future when the pieces of the past will come together and make sense.

Animate marks in conversation with each other. I eavesdrop on them. They say, “Hold onto something.”

What do I hold onto? A rubber band squeezing my wrist, a PLU sticker stuck to the metal back of my phone, a tea bag string wrapped around my glass cup handle.

Writers say, “The specific is universal.” I am myopic. Intuit a whole I never see.

A scene projected on each of the strewn puzzle pieces: a handful of dirt hits a girl’s chest, her dress tears on a branch, she rolls down a hill and into a lake.

Imagine the child’s hand you compare in scale to Mary’s scraps. It holds her miniature seas, fields, and staircases. Expanses leading elsewhere from their ceramic surfaces.

No one tells you how to start but it’s harder to know when to stop, turn back, retrace your steps to the first wrong turn.

Take refuge from the red clay desert in a thorn forest. Look up. I’m blinded by the sun. Sometimes we don’t want to see. Who cares what the staging of “reality” conceals?

Artifice creates distance. Held at arm’s length, I marvel at Mary’s miniatures. Doll houses with locked doors and tinted windows.

Marks cluster and fall apart: ripples, blades of grass, and steps. Footsteps. Alone together.

How do I let go? It rained softly this morning, then, hard. As I opened my umbrella, a receipt fell from my hand. I’ll look for it tomorrow. A trace.

Inoperative words #3

Elisa Taber

22 June, Montréal, 2:09 pm

Make a world from scraps, not scratch. Waves crumble on the shore. A wet page in the fold. Words washed away.

I found a story on a bus. A skeleton recovers its lost bones by retracing its steps.

Communication (intimacy) and meaning are at stake. Keep quiet until you have something to be misunderstood.

Your touch, Mary, is light. I dissociate imagining the invisible elsewhere you point at.

A bird rises above towering figures. Their faces become halos its wings caress.

A face made of feathers. Eyes outlined in red. Feel pre-articulated thought. Perforate the vessel. See it, bleed.

Silhouettes are people behind curtains. Inaudible. Crash.

Fear creates distance. Hold the one beside you or pray to the bodiless. Desires change as you grow older.

Thirst, sleep, hunger. Aware of what you lose.

I sent you, Tom, a photograph of the Mesoamerican Dance of the Flyers. Ropes around the feet of bodies circling a church dome.

Illusions keep me afloat. Virtual proximity and false otherworldliness.

The rope is taut. Elsewhere—here now.

Shrink, grow wings, and fly out the window, over a winding stone path, and through the woods (between braided thorn branches), alight on a boulder between two rivers and shed wings.

“If I escape, can I return?”

Tom Melick

June 24, Sydney, 8:10am

Your message arrives on my way home. On the back of the bus seat in front of me someone has drawn a spiral.

Lines lead us elsewhere. Even a stain, as Da Vinci noticed, “can arouse the mind to invention”.

An elsewhere that never fully takes form, an image that escapes formulation. An image that isn’t information but communication.

Is that what keeps me looking? When the image opens into an inoperative moment.

As you say, parts of a whole that come together and apart. An obverse-image to everything we “must” do, “must” see, “must” know. I’m so tired of musts.

Most images show the world as it is, finished. But some come with their own incompleteness, like a cloud they form and disperse.

When I get home I look again at “Long Life Bricks”. A surface hospitable to incomprehension. That’s one way to understand it: let the picture remain a code that’s never cracked.

Lines are everywhere. New and ancient. Glistening in the sun, I’ve just seen the paths the slugs took during the night.

In Mary’s work I try to follow where the hand once was, the path it took. Looking becomes reconstructing. Invention.

I try to follow you too, as you fly off the page, from your desk. You make wings one word at a time until you’re somewhere above the sentence. When you come back down we’ll talk again.

These exchanges took place alongside Mary MacDougall’s exhibition, Ceramic Papers, 28 May – 25 June, 2022.

Elisa Taber writes and translates herself into an absent presence. An Archipelago in a Landlocked Country is her first book.

Tom Melick makes books and pamphlets at Stolon Press, and edits Slug with Elisa.